America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy

by Naoko Shibusawa

Harvard University Press, 2006, 397 pages

Naoko Shibusawa's Ph.D. dissertation at Northwestern University dealt with

"race, gender, and maturity" as key factors in reconfiguring the Japanese enemy

in American society between 1945 and 1964 after the end of the Pacific War.

America's Geisha Ally expands her dissertation topic into a book, which turns out

to be quite fascinating and readable although considered an academic work with

75 pages of endnotes. The book's seven chapters explore distinct aspects and

events of how American views of Japanese people changed in the postwar period.

Shibusawa argues that postwar public discourse in the U.S. regarding America's

relationship to Japan assumed two universally recognized hierarchical

relationships—man over woman and adult over child. She explains, "Portraying

Japan as a woman made its political subjugation appear as natural as a geisha's

subservience to a male client, while picturing Japan as a child emphasized its

potential to 'grow up' into a democracy." She explores how many Americans after

the end of the Pacific War "began seeing the Japanese not as savages but as

dependents that needed U.S. guidance and benevolence" by conceiving of the

relationship between the two countries in the mutually reinforcing frameworks of

gender and maturity, which helped to reduce and minimize intense racial hostility

prevalent during World War II.

Each of the seven chapters supports Shibusawa's argument but can also be read

independently or in any order. The first two chapters give an overview of how

American attitudes changed toward Japan in the first few years after the war's

end. Chapter 1 explains how the notion of Japan as childlike and feminine

reframed America's relationship with Japan and helped Americans see the recently

disparaged enemy as a valued ally in the Far East. Chapter 2 describes how

Americans considered Japanese people as needing guidance and teaching due to

their immaturity. General MacArthur's statement in 1951 summarizes this attitude

along with the belief that the Germans, although an enemy in World War II, were

equal to Americans in terms of cultural achievement (p. 55):

If the Anglo-Saxon was say 45 years of age in development in the

sciences, the arts, divinity, culture, the Germans were quite mature. The

Japanese, however, in spite of their antiquity measured by time, were in a

very tuitionary condition. Measured by the standard of modern civilization,

they would be like a boy of 12 as compared to our own development of 45

years.

The last five chapters discuss specific aspects or events that changed

Americans' view of Japanese people: transformation of Emperor Hirohito to a

peace-loving and model family man, trials of Tomoya Kawakita and Iva Toguri

d'Aquino (Tokyo Rose), postwar scholarships for Japanese students to attend

American universities, the Hiroshima Maidens project of 1955-6 that provided

plastic surgery for 25 women disfigured by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima,

and several Hollywood films that depict Japanese characters such as Sayonara (1957) and

Teahouse of the August Moon (1956) starring Marlon Brando and Geisha Boy (1958)

starring Jerry Lewis.

Chapter 5 discusses postwar scholarships for Japanese students to attend

American universities, including the Johnstone scholarship, whose first Japanese

recipient was

Robert Yukimasa Nishiyama, described as a veteran of the Japanese Imperial Navy

who had been assigned to the Kamikaze Corps during the war. Life magazine covered Nishiyama's

story as a freshman at Lafayette College in an article entitled "Kamikaze Goes

to College" in the edition dated October 4, 1948. The magazine article and

Shibusawa's book do not provide any details about Nishiyama's service in the

Kamikaze Corps, so this aspect of his background possibly could have been

exaggerated for publicity purposes.

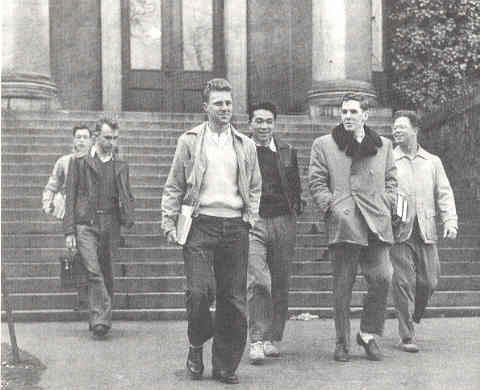

Robert Nishiyama (third from right)

with fellow Lafayette College students

The scholarships provided to Japanese men had the overall goal of

re-educating the Japanese in the areas of peace and democracy. The

scholarships were created "not only to educate Japanese students but also to

teach Americans to confront their intolerance by dealing with Japanese students

in their midst" (p. 184). Nishiyama turned out to be an excellent selection in

that he "extolled the generosity, openness, and goodwill of the Americans he had

encountered" and was "a grateful pupil of American altruism and wisdom" (pp.

201, 203). Nishiyama appealed to American audiences as a "polite, earnest,

grateful, and complimentary" student, and he challenged "readers or listeners to

rethink their preconceptions about the Japanese, but did so modestly and

judiciously" (p. 205). Shibusawa concludes on the effects of the scholarships to

send Japanese students to American universities, "The scholarships no doubt

benefited individual Japanese, but instead of fulfilling their stated mission to

promote pro-American sentiments in Japan, these programs were more effective in

allowing some earnest Japanese individuals to show their people in a better

light" (p. 212).

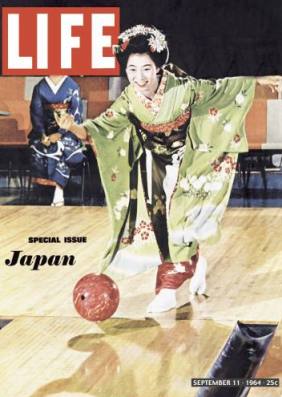

Image of a geisha bowling served as cover picture for

Life

magazine's special issue on Japan in September 1964

America's Geisha Ally provides a wealth of information

from popular culture related to how Americans perceived Japan and its people in

the postwar period. The author focuses exclusively on American viewpoints,

but it would have been interesting to contrast these with how Japanese people

considered the Americans during the country's occupation and the period after

the American's left in 1952. Shibusawa explains in captivating detail how

history's truths can be reshaped to serve the victor's objectives.

|