|

|

|

|

In freshman dress Robert Nishiyama wears a maroon "dink"

with his class numerals, a maroon knitted tie and a pin with his name on it.

He carries matches with which he must light the upperclassmen's cigarets. He

must also allow seniors to precede him through doors. Like all freshmen, he

is supposed to do this until Christmas vacation. |

|

|

Kamikaze Goes to College

Life, October 4, 1948, pp. 124-8

Introductory Comments

Robert Yukimasa Nishiyama, a former Japanese Navy pilot in the

Kamikaze Special Attacks Corps, became the first Japanese person to attend an

American university after the end of World War II [1].

The five-page article with 14 photographs published in the fall of 1948 in

Life magazine focuses on his arrival and reception at Lafayette College in

Pennsylvania but provides almost no details on his life as a Navy pilot. One

photograph shows Nishiyama's "cadet class in the summer of 1944 posed in front

of cadet quarters," but the caption and article do not give any more details

regarding his Navy experience other than that he ended the war still waiting for

orders to make a suicide attack on American ships.

Nishiyama received a scholarship that had been

established with $10,000 from a life insurance policy on Robert Johnstone, who

had died fighting in Luzon in May 1945 as part of the U.S. Army. The Life

article indicates that the establishment of a scholarship to assist Japanese

students was the dying wish of Robert Johnstone, but actually it was not his

dying wish since his father convinced the rest of the family to establish a

tuition scholarship in his memory at Lafayette College, where Robert had

attended for six months as an engineering student prior to being drafted into

the Army [2]. The scholarship was established in the

fall of 1945 for a Japanese student, but Occupation authorities in Japan did not

allow Japanese to travel overseas right after the war's end, so Nishiyama, as the

first student from Japan to attend an American university after the war's end,

did not did not enter Lafayette College until the fall of 1948 [3].

When Nishiyama was drafted into the Japanese Navy, he

was in his third year of studies of English at the Tokyo Foreign Language

University. He was married to Helen Matsuoka, who had grown up in California although

she had been born in Japan, and she had graduated from Stanford University just

prior to the start of the Pacific War [4]. After the

war Nishiyama worked as translator for the American military in Korea. He entered

Lafayette College in the fall of 1948 when he was 22 years old, and a former

Marine named Lew Bender, age 26 at the time, asked to be his roommate. The

college agreed since they were both older than average age. Nishiyama graduated

from Lafayette College and returned to Japan, where he had a successful career in

business. From 1962 to 1985, he served as president and general manager for the

Japanese subsidiary of a U.S.-based electronic components manufacturer. He then

worked as marketing vice-president for the Pacific Basin of another U.S.-based

electronics company [5].

Naoko Shibusawa in her 2006 book titled

America's

Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy explores how many Americans after

the end of the Pacific War "began seeing the Japanese not as savages but as

dependents that needed U.S. guidance and benevolence" [6].

In Chapter 5, she discusses that postwar scholarships for Japanese students to

attend American universities, including the Johnstone scholarship, shared the

overall goal of re-educating the Japanese in the areas of peace and democracy [7].

The scholarships were created "not only to educate Japanese students but also to

teach Americans to confront their intolerance by dealing with Japanese students

in their midst" [8]. Nishiyama turned out to be an

excellent selection in that he "extolled the generosity, openness, and goodwill

of the Americans he had encountered" and was "a grateful pupil of American

altruism and wisdom" [9]. Nishiyama appealed to

American audiences as a "polite, earnest, grateful, and complimentary" student,

and he challenged "readers or listeners to rethink their preconceptions about

the Japanese, but did so modestly and judiciously" [10].

Shibusawa concludes below on the effects of the scholarships to send Japanese

students to American universities [11]:

The scholarships no doubt benefited individual

Japanese, but instead of fulfilling their stated mission to promote

pro-American sentiments in Japan, these programs were more effective in

allowing some earnest Japanese individuals to show their people in a better

light. Rather than spreading good news about America in Japan, the students

helped Americans accept the Japanese as their "junior allies" in the Far

East.

Only a sample of photographs from the original article

have been included on this web page.

A Japanese suicide pilot starts his freshman year

at Lafayette on a scholarship started by a dead GI

A little more than three years ago Ensign Robert Yukimasa Nishiyama, 19,

pilot in the Kamikaze Corps of the Imperial Japanese Navy, was awaiting orders

to go out and crash his explosive suicide plane into a U.S. warship. At about

the same time Private Robert Stansbury Johnstone, 18, a U.S. soldier in the

Philippines, had a premonition of death. He wrote home and asked his parents to

use his $10,000 government insurance to establish a scholarship which would

teach his enemies the American way of life. Shortly thereafter Johnstone was

killed by a Jap during the fighting on Luzon. And last week Robert Nishiyama,

whose country had surrendered before he was sent on a mission, showed up at

Lafayette College in Easton, Pa., as a student on the scholarship which

Johnstone's money made possible.

Johnstone's mother, when she met Nishiyama

for the first time, grasped his hand and said warmly,

"Welcome, welcome, we're so glad you're here at last."

Nishiyama had been one of 20 Japanese applicants for the Johnstone

scholarship. A foreign-language student in Tokyo, he speaks English very well

and impressed the scholarship board by his perfectly written letters. When he

got to the Lafayette campus he went to the president's office to meet Private

Johnstone's family. He stood around nervously until the Johnstone family came

in. Mrs. Johnstone quickly ran up and welcomed him, followed by Mr. Johnstone

and their younger son Bruce, a Lafayette freshman who towered over Nishiyama.

"Bob," Mrs. Johnstone said quickly, "was almost as tall as Bruce is." Moved by

the meeting, Nishiyama could only say to each of them, "I don't know how to

thank you." Then, with new roommate, Lewis Bender, an ex-Marine who is studying

to be a minister, Nishiyama went off to sign the papers, take the tests and buy

the "dinks" that go with every freshman's first college days.

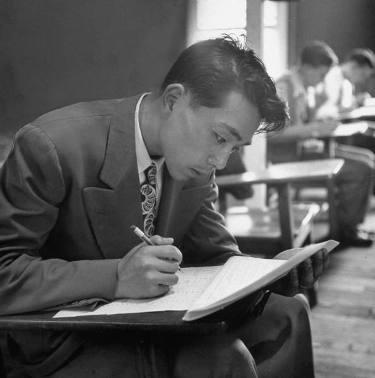

Taking a test, Nishiyama reads questions on one page

and checks answers on another. He once attended an

American school in Tokyo but had never seen this type of

test. He was embarrassed when it had to be explained.

He finds college life is fast and friendly

Nishiyama was prepared for almost anything but the casual reception he got

from Lafayette classmates. He had learned something of the U.S. from his wife,

who had lived here most of her life and had graduated from Stanford University,

and from U.S. soldiers for whom he had worked as interpreter. In spite of this

he expected to find some bitterness and some people who would blame him for the

war. But his classmates were friendly and paid little attention to him. He

walked hesitantly into Easton to buy a pair of sneakers and found that the

storekeepers, who had heard of him, were very pleased to see him. He walked

back, and a sophomore took him to dinner. Then, suddenly, he found he was just

one of 500 confused freshmen going through an indoctrination program. He bought

books. He met his adviser. He selected his courses, signing up for American

history, English and French. When he graduates he wants to go back to Japan and,

in the spirit of Johnstone's scholarship, teach international relations.

Ensign Nishiyama, as naval cadet

in 1944, weighed 170 pounds, has lost 35.

Lafayette College has a web page entitled "Japanese

Ex-Kamikaze Pilot Attended Lafayette" about Yukimasa Nishiyama.

Notes

1. Shibusawa 2006, 184.

2. Shibusawa 2006, 185, 191.

3. Shibusawa 2006, 185-98.

4. Shibusawa 2006, 188.

5. Shibusawa 2006, 210.

6. Shibusawa 2006, 5.

7. Shibusawa 2006, 186-7.

8. Shibusawa 2006, 184.

9. Shibusawa 2006, 201, 203.

10. Shibusawa 2006, 205.

11. Shibusawa 2006, 212.

Source Cited

Shibusawa, Naoko. 2006. America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining

the Japanese Enemy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

|