|

|

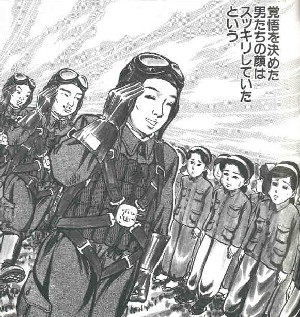

Sendoff to kamikaze pilots (p. 83)

|

|

|

|

Sensōron (On War) has three chapters that cover

tokkōtai, Chapters 3 - Tokkō seishin (Special Attack Corps spirit), 17

- Kuni o mamoru tame no monogatari (Story about protecting the country),

and 21 - Ko o koeru yūki to hokori (Courage and pride that surpass

individuals). Kobayashi explains that the six thousand tokkōtai members who

died included not only kamikaze pilots but also men who died in attacks using

other types of weapons such as ohka (piloted rocket-powered gliders), kaiten

(manned torpedoes), and explosive motorboats.

Chapter 7 gives the most information about the history of

Japan's tokkōtai (special attack corps) and opinions about their suicide

attacks. During the war, Americans had several misconceptions about the

motivation of kamikaze pilots (p. 80). Some thought pilots had been chained to

their seats, and others believed they drank and injected themselves with drugs

before their suicide missions in order to have their senses numbed prior to

departure. Many Americans during the war believed the pilots were fanatical

nationalists. Kobayashi says that the leftists incorrectly portray that tokkōtai members

were victims who died in vain. To counter the leftist view, he quotes three writings

of kamikaze pilots published by the Yasukuni Jinja (1995, 1-2, 5-6; 1997, 77-78) in order to show

that they died voluntarily for their country, homeland, families, and emperor.

He includes the touching letter written by

Masahisa Uemura to his young

daughter Motoko.

Chapter 17 starts with a visit by the main character to the

Etajima Museum of Naval History, where he views photos and last letters of

kamikaze pilots. He thinks back to the war when Japanese people honored these

young men as heroes who fought on behalf of their country. Many Japanese today

want to live long lives for themselves, but few have the spirit of kamikaze

pilots who become heroes during the war by protecting Japan with their

lives.

Chapter 21 condemns the individualism rampant in modern

Japanese society, which causes many societal problems such as domestic violence

and excessive greed. In contrast, the kamikaze pilots and other tokkōtai

members willingly gave their lives in defense of their country. Kobayashi

quotes on page 352 a diary excerpt from Lieutenant Junior Grade Toshimasa

Hayashi, a member of the kamikaze special attack corps who died at

sea east of Honshū on August 9, 1945 (Kōsaka 2001, 146):

I can die to protect my homeland. For me my homeland is the

land and people I love. Leaving behind my homeland, now I will be able to look

down at my homeland from afar. In the near future I will gaze at Japan with a

broad view. Since I will leave Japan, at that time I will recognize Japan as my

country and my homeland in the true sense. I can die to protect that purity,

dignity, preciousness, and beauty.

Kobayashi laments that modern Japanese no longer have

Hayashi's kind of commitment. In Chapter 21, Kobayashi also contrasts Japan's

tokkōtai with Islamic radical fundamentalists who commit terrorist acts against

civilians (p. 356). He concludes that the two are fundamentally different since

a suicide attack by tokkōtai was a battle tactic during a time of war against

enemy warships. The tokkōtai members only made suicide attacks "in order

to protect their country where their loved ones lived."

Although many individual facts and arguments presented

by Kobayashi seem reasonable and well-supported, his ultimate conclusions often

are at odds with historical evidence and general public opinion. He portrays

tokkōtai as heroes ready to give their lives for their homeland and families.

Many young men during the war definitely had such an attitude, but Kobayashi

seems to only present arguments to support his ultranationalist views. He

remains silent on certain subjects, such as government and military coercion

and propaganda, tokkōtai members who wrote against the military, and the

failure of Japanese leaders to surrender even when Japan had no chance to

escape defeat.

Sources Cited

Kōsaka, Jirō. 2001. Tokkōtaiin no inochi no koe ga kikoeru

(Hearing the voices of lives of special attack corps members).

Originally published in 1995. Tōkyō:

PHP Kenkyūsho.

Pons, Philippe. 2001. A cartoonist rewrites Japanese history. Le

Monde diplomatique. October. <http://mondediplo.com/2001/10/09manifesto>

(October 15, 2004).

Yasukuni Jinja, ed. 1995. Eirei

no koto no ha (Words of the spirits of war heroes), Volume 1.

Tokyo: Yasukuni Jinja Shamusho.

Yasukuni Jinja, ed. 1997. Eirei

no koto no ha (Words of the spirits of war heroes), Volume 3.

Tokyo: Yasukuni Jinja Shamusho.

|