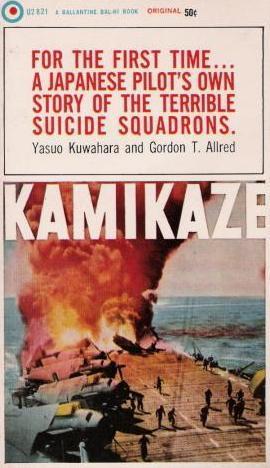

Kamikaze

by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon T. Allred

Ten Historical Discrepancies

by Bill Gordon and Yuko Shirako

Article originally published in October 2006 on web site of American

Legacy Media.

This article analyzes ten significant historical

discrepancies in the book Kamikaze, written by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon

T. Allred. Each discrepancy discussed in this article has three sections: (A)

details from book, (B) historical facts related to subject, and (C)

possibilities to explain inconsistencies between book's statements and

historical facts. Kamikaze was published originally in 1957, but

this article analyzes the book by using the 1982 edition.

The book Kamikaze is an autobiographical account of

Kuwahara's 18 months in the Japanese Army, but some background information on

the relationship between Kuwahara and his coauthor Allred would be helpful to

assess the historical discrepancies contained in the book. Allred wrote the book

Kamikaze in English based on information provided to him by Kuwahara.

They used an interpreter for almost all of their conversations over a ten-month

period starting in the summer of 1955. Allred first wrote out Kuwahara's story

in an 80-page draft. After reading the entire draft written by Allred in

English, Kuwahara corrected any errors and offered additional suggestions. This

account written by Allred was published as an article entitled "I Was a

Kamikaze Pilot" in the January 1957 issue of Cavalier

magazine. After Allred returned from Japan to the U.S., he wrote a rough draft

of the book Kamikaze based on the published magazine article, extensive

notes from his conversations with Kuwahara, and background reading. Allred sent

this book draft to Kuwahara, who only answered a few questions due to his poor

health at the time. The book Kamikaze was published in 1957 without Kuwahara's

making comments on the entire manuscript.

The ten most significant historical discrepancies in

Kamikaze are the following:

1. Hiro Air Base

Book: Kuwahara served in

the Japanese Army at Hiro Air Base from February 1944 to early June 1945 during

his basic training, flight training, fighter training, and fighter squadron

assignment. He returned to Hiro Air Base in late June or early July 1945 after a

week at Ōita Air Base and two to three weeks at a small air base in Formosa. He

remained at Hiro until August 23, 1945.

Facts: The Japanese Army

did not have a base at Hiro or any air bases near Hiro. The Navy had two major

production facilities in Hiro: 11th Naval Aviation Arsenal and Hiro Naval

Arsenal. During WWII, these factories produced various naval planes such as Suisei bombers,

Type 0 Observation Seaplanes, and Shiden-kai fighters. These two facilities also repaired planes and

manufactured aircraft engine and other parts. On May 5, 1945, 148 B-29s

bombed these facilities and destroyed them.

Kuwahara drew a map of Hiro Air

Base buildings in order to assist Allred's writing of the book. This map

supports a statement in Chapter 4 that Hiro Air Base had 48 barracks housing 15

men apiece and "a training ground, school, dispensary, storage houses, plus a

variety of buildings and offices." An American plane took an

aerial

reconnaissance photograph of Hiro prior to its being bombed on May 5, 1945. The

photograph shows that the Hiro Air Base buildings drawn by Kuwahara are actually

several buildings of the 11th Naval Aviation Arsenal in Hiro. Chapter 4

describes a "long, narrow airstrip running the full length of the base," but the

photograph shows no such airstrip next to the buildings drawn by Kuwahara. The

Hiro factories did have a short taxiway to the water, where facilities existed

to put seaplanes into the water or to load planes onto ships.

Kure Naval Air Group, based in Hiro from 1931, used an airfield across a small

river from the Navy's factories. Jungo Kaku, a Japanese Navy pilot who during

WWII flew to the airstrip used by the Kure Naval Air Group to pick up a repaired

plane, said in an interview that he has no knowledge of any Army air base

located at Hiro. No fighter squadron was stationed at Kure Naval Air Group's

airfield in Hiro during WWII. A fighter squadron called the Kure Naval Air Group

Fighter Squadron operated from Iwakuni Air Base in Yamaguchi Prefecture. This

squadron reorganized in August 1944 to become Naval Air Group 332.

Test pilots assigned to the Hiro

naval aircraft factories also used the Kure Naval Air Group airfield for

manufactured and repaired planes.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara was actually in the Navy rather than the Army since Hiro and its

surrounding area did not have an Army base. However, it seems unlikely that

Kuwahara would misidentify his military service branch. The book states

specifically in several places that he served in the Army, and he trained to

become a pilot of a popular Army fighter named the Hayabusa. Also, the

book uses Army ranks to refer to various individuals.

Perhaps Kuwahara was in the group

of test pilots associated with the naval arsenals in Hiro. However, these test

pilots would have been experienced pilots to test planes manufactured and

repaired there. The book states that Kuwahara had his basic, flight, and fighter

training at Hiro, but no organization or facilities existed in Hiro for this

type of training. The book states that Kuwahara entered the Army at age 15 in

February 1944, so he would have been too young to be a test pilot.

2. Kamikaze Attack Date

Book: On June 10, 1945, a

squadron of 12 kamikaze pilots flew from Ōita Air Base to Kagoshima Air Base for

a refueling stop and then took off from Kagoshima to make an attack on a group of

25 American ships. All pilots died in the attack. They sank one destroyer and

one tanker.

Facts: On June 10, 1945,

the only kamikaze attacks were made by three fighters that made sorties from the

Army's air base in Chiran.

Kagoshima Air Base was a Navy air

base rather than an Army air base.

Japanese records of special

attack force (tokkōtai in Japanese) or kamikaze deaths indicate only 12

men made sorties from Kagoshima Air Base during the entire war. On March 11, 1945,

the 12-man crew of a Type 2 Flying Boat made a sortie from Kagoshima as one of the

lead planes in the kamikaze attack by Ginga bombers on American ships

anchored at Ulithi Atoll. An American patrol bomber shot down the flying boat.

Kamikaze planes did not sink any

tankers during the war.

Possibilities: Perhaps the

12 kamikaze pilots made sorties from another base in Kagoshima Prefecture on a

different date. This could be possible based on the large number of kamikaze

pilots who made sorties from bases in Kagoshima Prefecture during the Battle of

Okinawa. It is most likely that the book's date would only be off by a day or

two. However, this does not appear to be correct. On June 8, there were the

following kamikaze sorties: 6 from Miyakonojō, 3 from Chiran, and 3 from Bansei.

These would not be the squadron of 12 planes that took off from one air base.

There were no kamikaze sorties on June 9. On June 11, there were 10 kamikaze

planes that made sorties from the Army's base in Bansei and 4 from Chiran. Nine of

the planes from Bansei were from the 64th Shinbu Squadron, which could not have

been the one mentioned in Kuwahara's book since this squadron never passed

through Ōita. After June 11, there were no recorded Army or Navy kamikaze

sorties until June 21.

Perhaps Kuwahara misidentified

the tanker that sank when hit by a kamikaze plane. However, there is no date

close to June 10, 1945, when both a destroyer and another type of ship sank on

the same date. The nearest date before June 10 when this happened was May 25,

and the nearest date after June 10 was June 21.

3. Friends' Deaths as Kamikaze Pilots

Book: Kuwahara's boyhood

friend named Tatsuno died as a kamikaze pilot in an attack on an American tanker

on June 10, 1945.

Oka, a friend of Kuwahara at Hiro

Air Base, made a kamikaze sortie from Kagoshima Air Base sometime in May 1945

about three weeks before June 10.

Facts: Japanese records of

special attack force kamikaze deaths do not mention any pilot named Tatsuno who

died after March 1, 1945.

Japanese records of Army special

attack force kamikaze deaths during 1945 mention one pilot named Oka. However,

this pilot made a sortie from Chiran Air Base on April 16, 1945.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Japanese wartime records are incomplete or incorrect. However, the current

listings of special attack force kamikaze deaths are considered complete and

accurate for the most part, although a very few discrepancies between listings

still exist. Japanese researchers have worked for several decades after the war

to improve the accuracy of these listings by contacting veterans and bereaved

family members. After the end of the war, several challenges existed to ensure a

complete and accurate listing of special attack force kamikaze deaths. Some

records were burned when surrender was announced. Also, some kamikaze pilots

made forced landings on the way to Okinawa and survived on small islands, even

though official military records indicated their deaths in kamikaze attacks.

Perhaps Tatsuno and Oka died as

escort pilots rather than kamikaze pilots, so their deaths would not be included

in Japanese listings of special attack force kamikaze deaths. However, the book

states specifically that Tatsuno made a sortie in a kamikaze squadron on June 10,

1945. Kuwahara witnessed his death as he crashed into and sank a tanker. The

book does not clearly state how Oka died, but it strongly suggests that he also

died in a kamikaze mission rather than as an escort pilot.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Ōita Air Base

Book: When American B-29s

destroyed Hiro Air Base in early June, Kuwahara moved to Ōita Air Base, where he

became an escort fighter for kamikaze squadrons. He was there for a few days

before he flew his first escort mission in which he accompanied 15 kamikaze

planes. He flew escort from Ōita for an unspecified number of multiple kamikaze

missions prior to June 10, 1945. The book implies that the kamikaze planes also

flew from Ōita since Kuwahara writes that it was better that he did not form any

close friendships at Ōita when referring to men selected for kamikaze missions.

Facts: Ōita Air Base was a

Navy air base rather than an Army air base.

During 1945, only ten kamikaze planes made sorties from Ōita Air Base and did

not return. This includes one Ginga bomber on March 18, another on March 20,

and eight Suisei dive-bombers led by Vice Admiral Ugaki after the Emperor

announced surrender on August 15.

Based on Hiro being destroyed in early June and Kuwahara waiting a few

days for his first escort mission, there would have been only one

opportunity in June 1945 prior to the 10th for him to fly an escort fighter

for kamikaze missions. On June 6, 25 kamikaze planes made sorties from Chiran Air

Base.

Possibilities: Perhaps Kuwahara meant another air base in Ōita

Prefecture rather than Ōita Air Base. However, the other two Ōita Prefecture

air bases, located in Usa and Saiki, were both Navy air bases. Also, no

kamikaze planes made sorties from these two air bases.

Perhaps Kuwahara escorted kamikaze planes that made sorties from Chiran on

June 6, 1945. However, the book indicates that the kamikaze squadrons were

at the same base as the escort squadrons.

5. Navy Plane in Army Kamikaze Squadron

Book: Tatsuno flew an

"all-but-defunct" Navy plane, a Mitsubishi Type 96 Fighter, when he led the last

three planes in the 12-plane kamikaze squadron that made sorties on June 10, 1945.

His plane was the only Navy plane in the squadron. Tatsuno was an Army fighter

pilot.

Facts:

Japanese records of tokkōtai (special attack force) kamikaze deaths do

not indicate that the Navy's Mitsubishi Type 96 Fighter was ever used for a

kamikaze attack.

There is

no known case where Army and Navy kamikaze planes joined in the same squadron

and made sorties from the same air base.

There is

no known case where a kamikaze pilot trained on an Army fighter and then

switched to a Navy fighter for a kamikaze mission.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara misidentified the plane, and it was actually an obsolete Army fighter.

Both the Army's Type 97 Fighter and the Navy's Type 96 Fighter were

single-engine, single-seat planes with fixed landing gear. However, it seems

improbable that an Army fighter pilot such as Kuwahara could not identify all

Army fighters in use during the war.

6. Daily Kamikaze Sorties from Formosan Bases

Book: Kuwahara states

twice that suicide planes made sorties each day during his two- to three-week stay in

Formosa starting on June 10, 1945.

Facts: Navy or Army

kamikaze planes did not sortie from air bases in Formosa from June 10 to 30,

1945.

Possibilities: Perhaps

there was some confusion in the dates in the book, so Kuwahara's time in Formosa

was actually earlier when kamikaze planes regularly made sorties. However, although

many kamikaze planes made sorties from Formosa from March to early June 1945,

Japanese records of special attack force kamikaze deaths indicate that there

never were three consecutive days of kamikaze sorties from Formosan bases.

7. Reconnaissance Flight Over Hiroshima

Book: Kuwahara was in

Hiroshima on August 6 when the bomb was dropped at 8:15 a.m. He was buried in

debris for nearly six hours, but he managed to climb onto an Army truck to

return the same day to Hiro Air Base, located about 12 miles southeast of

Hiroshima. On August 8, he flew from Hiro in a Shinshitei reconnaissance

plane (Ki-46, Army Type 100 Command Reconnaissance Plane) for two hours to

survey the damage caused by the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. While flying over

Hiroshima, he learned that Nagasaki had also been bombed. Kuwahara does not

mention that he ever flew in a Ki-46 reconnaissance plane before this date.

Facts: The Ki-46

reconnaissance plane has two engines and a normal crew of two or three depending

on which Ki-46 version.

Japanese pilots in WWII normally

had flight training on a particular plane type prior to making flights. It would

be especially rare for a pilot to switch from a single-engine fighter (e.g., Hayabusa fighter flown by Kuwahara) to a much larger twin-engine plane such

as the Ki-46 reconnaissance plane. The fact that a Ki-46 had a normal crew of

two or three would make this even more difficult for an untrained pilot to fly

the plane alone.

The atomic bomb exploded over

Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, at 11:02 a.m.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara flew the Ki-46 reconnaissance plane from Hiro Air Base with a second

crewmember. However, the book provides no hint that he flew in the plane with

anyone else. It is not clear why Kuwahara, heavily injured from the atomic bomb,

would be selected as the pilot for a plane type he had never flown before. There

is no evidence that Hiro had any Ki-46 reconnaissance planes.

Perhaps Allred mistakenly wrote

August 8 as the date of the Nagasaki bombing since it would have been August 8

in the U.S. when it was 11:02 a.m. on August 9 in Japan. However, he correctly

gives the date of the Hiroshima bombing as August 6.

8. Notification of Kamikaze Mission

Book: When Kuwahara

returned to Ōita Air Base from Formosa at the end of June 1945, Captain Tsubaki

told him individually that he would go on a kamikaze mission sometime in the

near future. Kuwahara returned to Hiro Air Base while Tsubaki remained at Ōita.

On August 5, 1945, Kuwahara received written orders that his kamikaze mission

was scheduled for August 8, but there is no mention of the planned sortie base

for his mission. He left Hiro on the morning of August 6 for a two-day home

leave, so it can be assumed that he would sortie from Hiro on August 8.

Facts: Japanese Army

kamikaze pilots who made sorties from mainland Japan normally were notified of their

assignments in a similar manner. First, pilots from the same base were assigned

to a tokkō (special attack) squadron. Almost all of these Army tokkō

squadrons during and after the Battle of Okinawa were called Shinbu Squadrons

with designated numbers (e.g., 60th Shinbu Squadron). Each squadron usually had

between 9 and 12 men, although some squadrons had less or more. Both the Army's

Shinbu squadrons and the Navy's Kamikaze squadrons generally are referred to as

kamikaze squadrons in English, but the Japanese Army never used the term

"kamikaze" to refer to its tokkō squadrons.

After establishment of an Army tokkō squadron, the men in the squadron generally spent several weeks

together in training, often at the same base. When the estimated sortie date

neared (usually about one day to one week prior to the estimated sortie date),

tokkō squadrons flew to bases located in the far southern part of Kyūshū

Island. The Army's main air bases for tokkō squadron sorties during the

Battle of Okinawa were Chiran, Bansei, and Miyakonojō. A tokkō squadron

would receive orders for the exact sortie date at one of the bases in southern

Kyūshū. Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, Commander of the 5th Air Fleet headquartered

in Kanoya until early August 1945, decided the dates and general times for the

mass kamikaze attacks made by the Navy and Army. These dates and times would

then be communicated to commanders at different bases and then passed on to the

pilots of kamikaze and conventional aircraft.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara's assignment to a kamikaze mission did not follow the general pattern

of other Army kamikaze pilots. However, it seems extremely odd for a pilot to

receive written orders regarding a kamikaze mission. The book does not mention

whether a tokkō squadron including Kuwahara had been formed or whether

Kuwahara would sortie solo from Hiro. The cancellation of the scheduled kamikaze

mission on August 8 is never discussed, even though Kuwahara had enough energy

to fly a two-hour reconnaissance flight over Hiroshima on the same date.

9. Training and Squadron Assignment at One Base

Book: Kuwahara had his

basic training, flight training, fighter training, and fighter squadron

assignment all at the same base in Hiro.

Facts: Japanese Army

pilots generally went to different air bases for their basic training, flight

training, and training on a specific type of aircraft. For example, Yukio Araki,

who died in a kamikaze attack from Bansei Air Base on May 27, 1945, did his

basic training at Tachiarai Air Base, his flight training at Metabaru Air Base,

and his training on an Army Type 99 assault plane in Pyongyang, Korea. In

another example, Kisaku Hisatomi, who died in a kamikaze attack from Chiran Air

Base on May 11, 1945, did his basic training at Kurume Reserve Officer Training

School, his flight training at Kumagaya Air Base, and his training on a Type 97

Fighter at Kakogawa Airfield. The Army did have different types of pilot

training programs, but pilots in each of these different programs almost always

went to more than one air base.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara joined a special Army air base that included all levels of training and

also regular squadrons. The book refers to several of Kuwahara's friends who

stayed at Hiro during their entire training. However, Army kamikaze pilots who

made sorties in 1945 had a completely different training history where they went to

more than one base.

10. Date for Bombing of Hiro Air Base

Book: One day in June

1945, 150 B-29s pulverized Hiro. Kuwahara transferred to Ōita Air Base, where he

stayed until June 10, 1945.

Facts: On May 5, 1945, 148

B-29s bombed the Navy's arsenals in Hiro and destroyed them.

Possibilities: Perhaps

Kuwahara made a mistake of one month when he mentioned the bombing of Hiro by

B-29s. He writes in Chapter 25 that he had known a woman named Toyoko in Ōita

for several weeks. Since he made a sortie from Ōita Air Base on June 10, 1945, he and

Toyoko could not have known each other for that long unless he actually moved to

Ōita in early May. He writes in Chapter 27 that he had been away from Hiro for

less than two months. This statement would be true if he had left Hiro on May 5

since he returned to Hiro at the end of June or early July.

Concluding Thoughts

These ten historical discrepancies certainly move Kuwahara and Allred's book

Kamikaze

to the category of fiction even though the book has been recognized for almost

50 years as an autobiographical account. In September 2006, Allred wrote that

two of Kuwahara's high school acquaintances in Hiro contended in 1998 "that he

had never won a national glider championship or been in the Japanese Army Air

Force." They said, "Kuwahara was merely one of many students drafted by their

government to support the war effort on that country's military bases." This

article provides substantial additional evidence to support their statements.

Kuwahara most likely worked at the Japanese Navy's aircraft production

facilities in Hiro and almost certainly never flew an Army plane.

______________________________________________

Yuko Shirako is the coauthor of this essay. The fiancÚ of her mother died

as an Army kamikaze pilot on May 4, 1945 (read

Yoko's Hopes and Losses for his

story).

This article was written in October 2006 based on the sixth

edition of the book published in 1982. A couple of changes have been made in the

2007 edition that affect the historical analysis in the article. First, the 2007

edition gives the full name of Tatsuno as Tatsuno Uchida (2007, p. 7), whereas the

1982 edition only used the name of Tatsuno. This addition of Tatsuno Uchida adds

more confusion, since both Tatsuno and Uchida are family names. All others in

the Army are referred to by their family names, but the 2007 edition uses

Tatsuno throughout the book other than the first mention of his name. This

mixing of family names for others in the Army with one given name (Tatsuno) does not make

sense. The second change that affects the article's historical analysis is the

omission in the 2007 edition of the sortie date from Ōita Air Base of Tatsuno's

kamikaze squadron. The 1982 edition specifically indicates the date as June 10,

1945 (p. 162), but the 2007 edition does not mention a date.

|