I Was a Kamikaze Pilot

by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon T. Allred

Cavalier, January 1957, pp. 6-9, 95-100

Introductory Comments

This condensed version of Yasuo Kuwahara's story in

the January 1957 issue of Cavalier magazine became the basis for a

full-length book entitled Kamikaze that was published later in 1957

(Kuwahara 2007, ix). Over the years Kamikaze sold over 500,000 copies and

greatly influenced American views of kamikaze pilots who carried out suicide

attacks against Allied ships from October 1944 to the end of World War II in

August 1945.

For several decades almost all Americans considered Kuwahara's book to be

true, but research published in 2006 showed historical inaccuracies of many

details (see Ten

Historical Discrepancies). The book and this magazine story contain several

far-fetched incidents such as pilots who drink the blood of other pilots and a

departing kamikaze pilot who cuts off his entire little finger so its ashes can

be sent to his family. Gordon T. Allred explains in "A Vital Explanation" in the

2007 version of Kamikaze that "in the year 2000, a Kamikaze movie

promoter, then researching related material in Kuwahara's home town of Onomichi,

encountered two men who said that his account was a fabrication. Both said they

had been his high school acquaintances and contended that he had never won a

national glider championship or been in the Japanese Army Air Force. Instead,

they maintained, Kuwahara was merely one of many students drafted by their

government to support the war effort on that country's military bases."

This magazine story and the book Kamikaze have the same basic plot with very

few inconsistencies. Some discrepancies between the two most likely came about

from having to cut certain episodes and characters for the much shorter

magazine article. Other differences may be due to changes made by the magazine's

editor. The book presents Kuwahara's life chronologically, whereas the magazine

starts with Kuwahara's escorting 12 aircraft in a kamikaze squadron that attacks

the American fleet near Okinawa, and then the storyline returns to Kuwahara's

days as a high school student and proceeds chronologically after that.

A supposed photograph of Yasuo Kuwahara (included below on this web page) is shown on the first

page of the magazine story. The next three pages in the magazine have

kamikaze-related photographs including a Zero fighter about ready to crash into

battleship Missouri, an ōka (called "baka" by Allies) rocket-powered

glider bomb, and a series of three images of an LSM that sank after being hit by

a kamikaze aircraft.

Notes have been added to the story in order to provide

comments on a few of the inaccuracies and implausible incidents. Click on the note number to go to the

note at the bottom of the web page, and then click on the note number to return

to the same place in the story. The notes for this story do not repeat the

book's historical inaccuracies already described in Ten

Historical Discrepancies such as no Army base in Hiro, no record that

Kuwahara's friend Tatsuno ever died in a kamikaze attack, and the incorrect

month for the American bombing of Hiro Air Base.

Here for the first time anywhere is the brutal inside story of the last

desperate days of the Jap Air Force—as told by one of the

doomed men whose country turned him into a human bomb

Mid-June, in Japan, 1945 [1]. I am a Kamikaze, a

Japanese suicide pilot. My own death orders have not yet arrived but I am

expecting them–any week, any day, any hour. In the meantime, until my orders

arrive, I have been assigned to escort my friends–Kamikazes like myself–on their

doomed missions against the mighty American task force at Okinawa. I am to

furnish fighter protection to the group, and on my return to the base I am to

report how successfully they died.

My friend Tatsuno is among them. Before takeoff, he comes up to me. A strange

smile is carved on his waxen face. He shakes my hand in a cold grip and gives me

something.

"It's not very much to send," he says. I sense his embarrassment.

I look away quickly. Tatsuno has just given me his little finger [2].

Our doomed men customarily leave something of themselves behind–a lock of hair,

fingernails or an entire finger–for cremation. The ashes are sent home to repose

in the family shrine. I promise numbly that the ashes of Tatsuno's finger will

rest with his ancestors.

It is almost time to go now and Kagoshima Air Base is vibrating with final

preparations. Mechanics have come to say good-by to the ships they have nursed

so long and tenderly. The planes are almost all obsolete, but it doesn't matter.

They are going on a one-way trip.

Twelve men have just received their last briefing from the commanding officer

and they stand on the runway in their flight suits, respectfully listening to

his parting words. Around the shaven skull of each is bound the Japanese flag,

with the crimson rising sun over his forehead. These flags, which their comrades

have signed in blood, symbolize the noble spirit of Nippon, as the Samurai sword

has done for our ancestors. Nearby, a knot of girls, with whom the Kamikazes

have had their last affairs, are starting to cry [3].

The Commanding Officer concludes with the words we have heard so often on

this runway in the past few months: "And so, valiant comrades, there is a place

prepared for you in the esteemed presence of your worthy ancestors." We bow.

We sing the battle song:

The Airman's color is the color of the cherry blossom.

Look, the cherry

blossoms fall on the hills of Yoshino.

If we are born proud sons of the Yamato

race,

Let us die fighting in the skies.

And drink the final toast. The sake glasses are raised and we cry "Tenoheika

Banzai!" (Long live the Emperor.) Some suicide pilots laugh and joke as they

climb into their planes; others are inscrutable. Most of them are afraid, but no

one wishes to show it.

It is perfect flying weather. The seasonal rains have subsided, leaving a

clear dome of blue. We take off and circle over the velvet mountains before

pointing out to sea. For the 12 Kamikazes, it is their last look at their

homeland and the three hour flight to Okinawa will be their last hours on earth.

My mouth feels like dry plaster as the minutes speed by and we draw closer to

our target. Planes are all about me, in tight formation, lethal arrows winging

at the American ships. I am beginning to tremble and I feel cold. My eyes are

unblinking balls of glass, my head throbs painfully. Far off, I see the swaths

of the first American ships. I count 25 of them.

Our lead suicide pilot waggles his wings, signaling the others and I wonder

what they are thinking. All 12 pilots open their cockpits and flutter silk

scarves. The hunters have spotted their quarry.

The moments glide by. The ships have sighted us now and they are beginning to

open up. We draw closer and I'm sweating. Now our leader is diving, dropping

vertically into a barbed wire entanglement of flak. He is aimed at a cruiser,

and for a moment I think he will make it. But no–he is hit and it is all over.

His plane is now a bright red flare that quickly fades and drops from sight.

Two more go exactly in the same way, exploding in mid-air. The fourth is

luckier. He dives unhit through the barrage. He's inside the flak umbrella near

the water. A hit! He's struck a destroyer just at the waterline. There is a

terrific explosion and then another and a third. The ship can't stay afloat. It

upends and is gone.

Things are happening now with incredible speed and confusion. One of our

planes is skimming low across the water while gunfire throws thousands of spouts

in the water around him. He is aiming at a carrier and will score a direct hit.

No, they get him. He bashes against the stern, inflicting little damage.

There are four big carriers in this striking force, well protected by

battleships and an outer perimeter of destroyers. The defense is almost

impregnable. Only a gnat could penetrate their fire screen. Two more suicides

try for the carrier and disintegrate near the water. Others have already dropped

into the sea. So far, I can be certain that we have sunk only one ship.

We have but one plane left. I try to make out who it is–the last plane in

formation. Of course, it's Tatsuno, and he's already diving. Fire spouts from

his tail section but he keeps going. His plane is a moving sheet of flame but

they can't stop him. A tanker looms below. A hit! An enormous explosion rocks

the atmosphere and the tanker goes down, leaving no trace except a widening

shroud of oil.

We had sunk a destroyer and a tanker, wounded a carrier, and (though I didn't

learn it till later) severely damaged a battleship. But I have no time to think

of our successes. The Hayabusa ahead of me waggles its wings to warn of danger,

and almost instantly a flock of Grummans pounces on us. Two of them are on my

tail, firing short bursts. Bullets tear at my stabilizer and one pierces my

windshield, inches above my head.

I try to escape by diving, only to find that I am a clay pigeon for the

convoy below. Miraculously, I streak through the flak and level out just above

the waves. One pursuing Grumman is not so lucky. He is blasted by his own ships

and hurtles into the sea. A geyser is his burial marker.

I climb for safety in my staggering ship, making for the black clouds on the

horizon. Now, tossed by the winds, I limp back to base [4].

I think that death–in the shape of an American plane–was on my tail, but as a

fighter pilot I was able to escape. But I am only a fighter pilot temporarily. I

too am a Kamikaze. Soon my turn will come.

Thirteen years have not dulled these memories. Today they are as vivid as

ever–tragic, fantastic experiences which few men will understand. This is the

story of my life as a Kamikaze pilot and the role that I played in the strangest

war ever known to man.

It would be difficult to say where the idea of a Japanese suicide warrior

began. Perhaps it was born with the country over 2,600 years ago when Zinmu,

First Emperor, descendant of the Sun Goddess, came to power. It has, at any

rate, been carried on for twenty centuries by the Samurai warrior who is willing

to die by his own sword.

My own experience as a Kamikaze began when I was only 15 and a high school

boy. I enrolled in a glider training course sponsored by the Hiroshima district,

of which my home town was a part. Throughout Japan students were being urged to

join programs that would prepare them for war. For me, the glider school was

perfect, something I'd been waiting for all my life–a chance to get into the

air.

Late that year I competed in the National Meet at Mt. Ikoma near Nara. Of the

600 qualifying glider pilots from different districts, six of us from my high

school captured the group championship. Immediately afterward I won first place

in individual competition. I was hailed as the best glider pilot in Japan.

As a result I was asked to enlist in the Imperial Army Air Force, and only a

few months later I began basic training at Hiro Air Base, about 30 miles from

Hiroshima. I wanted to enlist, but even if I hadn't, I had no recourse. It was a

matter of honor. Men who entered Japanese military life were expected to say, "I

go to die for my Emperor and my country." It wasn't an easy decision for a

15-year-old boy. I had no desire to die.

And so, I said a sad good-by to my family and went to Hiro where I found

another world. Sixty of us were assigned to four barracks and given an

orientation by one of the sergeants or "hanchos." He showed us how to make beds,

display our clothes, and polish our boots. Shoto Rappa (Taps) would be played at

9 p.m. If we were not perfectly neat and clean at all times, we would pay for

it.

Regulations like these were not much different than those in any military

unit. The great difference was how they were enforced. So strict was the

discipline, so fierce the punishment that many men did not survive. American

prisoners of war, victims of Japanese atrocities, often received no worse

punishment than we. Punishment served two purposes–it created discipline and it

developed courage. Anyone who could withstand the hanchos could stand up to the

enemy.

We got a taste of it the first night. I lay awake like a rabbit in a trap,

thinking of the tough training. Most of the boys were a year or two older than

myself and I wondered if I'd be able to bear up.

Suddenly the door burst open. The hanchos were making their first inspection.

Tense, I watched the yellow play of their flashlights and listened to their

mutterings.

Moments later we were driven from our beds with slaps, kicks and commands.

"Outside, mamas' boys," a hancho shouted.

A hand cuffed me. "Hey bozu (baldy)" someone said, referring to my shorn

head, "move out!" I was booted soundly out the door.

We were lined up, facing the barracks. A fat hancho began cursing us. He told

us that we could live like sloppy pigs if we wanted to. "Of course," said he,

"we wish to acquaint you with some of the consequences beforehand."

He made a motion and was handed a ball bat. "Do you know what this is for?"

he shouted. We knew the meaning all right. The bat was traditionally used to

instill men with the Japanese fighting spirit.

"Yes, Sir." The response was weak.

"Oh, come now. I couldn't hear you." This time we answered a little louder.

"Too feeble. When did you stop sucking milk from your mothers? I'm afraid

we'll have to punish you."

A metal bar, waist high, ran the length of the barracks. We were ordered to

bend over it and grasp it with both hands. "Now," said the hancho, "We shall put

some spirit into you!"

There was a smack and the first man in line grabbed his rear. Two assistant

hanchos had moved in with bats. The sound of hard wood striking flesh came

nearer. There were gasps of pain. Those who protested too audibly got additional

blows. My body jolted and fire shot though my buttocks. Gritting my teeth, I

grabbed myself and danced.

Later as we groaned in our beds, the hancho lounged in the doorway, the light

cutting across his puffy face. Removing the limp cigarette from his sneer he

called, "Hey, ojosan (girls). Do you know what the bats are for now?"

"Yes, Sir!" We bellowed. He chuckled and bade us a tender goodnight.

"The Pig," as we called the fat hancho, gave us a talk the next day. He said,

"The time has come for you to become men. As men, you will carry the weight of

Japan–and soon the rest of the world–on your shoulders. You must learn to follow

every instruction perfectly. Yesterday you failed to comply with instructions

regarding neatness in the barracks. In one barracks a shoe brush was missing. In

two others, ash trays were not placed properly on the tables. Next time I shall

be forced to put some real spirit into you. By the time you finish training

under Hancho Noguchi, you will truly be able to withstand pain. You will be able

to laugh at a little thing like the ball bat. I will make men of you."

Certainly he did his best. On our second night at Hiro he showed us a game

called "Taiko Binta." According to the Pig, we had been sloppy in ranks and had

not recited correctly the five main articles of military conduct in the Imperial

Oath.

"All right, playboys." The Pig leered, "we shall now play a game. Make two

ranks!" We lined up facing each other. Approaching one man, the Pig said, "I

will demonstrate. Now we are adversaries. The object of the game is

simply–this!" He struck with his fist and the boy toppled over.

Then he commanded men in one rank to strike the men across from them in the

faces. When they hesitated he said, "Perhaps you need another demonstration."

Again he struck. A man staggered and held his face. Blood oozed through his

fingers.

"Now, on the count of three, first rank!" I heard the count. We began

striking. "Harder! Harder!" The blows were beginning to hurt. I backed away

until a hancho began whacking my thighs with a bat. Instinctively, I threw one

arm across my legs and got a numbing blow on the elbow. He then grabbed me,

sinking his fingernails into my neck.

"Draw blood!" he shouted.

The eyes across from me were those of a scared animal. I wanted to quit but

the bat was searing pain across my back. I whirled and for an instant would have

killed the hancho, but he drove me back with stinging blows. "Next time, your

head will roll on the ground!" he bellowed.

"Come on, hit me!" the boy across from me was urging. My knuckles met his

cheek. "Harder!" the assistant screeched. I hit again and again until my

knuckles were raw and bleeding.

That night I was too swollen to sit and it was painful to lie down. I was

quietly groaning in the dark, when Nakamura, the boy with whom I'd exchanged

blows, limped over to talk. We apologized for having hit each other and talked

quietly for a while. Eventually I fell asleep, feeling better because I had

found a friend.

In the morning after a painful night we were all covered with bruises. We

limped along to the first formation grunting with soreness. The Pig's gaze was

almost benign as he inquired about our health. "You are still soft, like girls,"

he said and suggested that a few minutes of running would limber us up. It was a

fast three-mile run and many of us passed out. The Pig wheeled about on his

bicycle, thrashing at us with a sturdy length of bamboo, alternately cursing and

wisecracking.

That day they put us through a dozen forms of torture. The worst was reserved

for the evening. We were lined up six inches from the barrack wall. Methodically,

the hanchos passed down the line and slammed our faces against the wood. One man

had his nose broken, another lost some teeth.

Always the Pig dinned into our ears that we must forget the past and think

only of dying for the Emperor. We were Japan's expendable men. Through our

deaths would come victory.

Because of this ordeal, my entire conception of life began to change. I was

sure that my family, my carefree school days, were only an illusion. To expect

to ever be out from the shadow of death was unthinkable. In one short week I'd

grown old.

Late at night when the punishment had stopped was the worst. In the dark we

lay thinking of our families, especially our mothers. After all, as the

Americans put it, we were "kids," scared kids, some of us only 15. It was then

that we shed our tears where no one could see and few could hear.

Some of the boys still had young voices and called aloud for their mothers in

their sleep. For such weakness, we were all punished severely. And the most

immature, including myself, were often embarrassed in various ways.

For example a hancho would eye one of us and say, "Hey Shinpei (recruit), are

you a man yet?"

Regardless of the reply, a demand would come to prove it. "Take down your

pants!" The hapless trainee would comply, standing shame-faced while the hanchos

made cracks about his endowment.

After two weeks, our families were allowed to visit us. A counter separated

the trainees from the visitors, convict style. We were forbidden to accept food

or presents, but my mother slipped some cakes under the counter. Almost every

boy had presents hidden under his mattress that afternoon. We decided to have a

party.

It was not the sort of party we expected. That night our beds were ransacked.

Our faces were bashed against the barracks walls. Then, with our boots tied

around our necks, we were forced to crawl, one by one, along the barracks hall

to the Pig's room to apologize. As we crawled to the side of his desk, he kicked

us in the faces.

Instead of getting better, the punishment got worse. As we got tougher, they

began running us five miles every day instead of two or three and those who fell

out were bludgeoned with rifle butts. Instead of exchanging blows with fists, we

used shoes with nails in them. There was not a man whose face was not shredded,

particularly around the corners of the mouth.

The torment never ceased. We became quivering things, frayed of body and

nerve. Men jumped in their sleep and moaned incessantly. Bitterness grew and

more than one of us spoke of killing the Pig.

Several deserted, but they were all captured and thrown in the army stockade.

Most of them were hanged from the ceiling by their wrists with iron weights

attached to their ankles and their naked backs were beaten with belts. Deserters

from all branches of the military were sent to army stockades where MPs did

anything they pleased with them. Often prisoners were tortured to death and

nothing was ever said.

My feelings at this stage were indescribable. None of it seemed real. So much

had happened so suddenly. A severely wounded man does not feel the raw pain at

first. The real suffering comes later. My nerves were deadened.

One evening I tried to enter the latrine but found it locked. After waiting,

I called and received no answer. A few of us, becoming suspicious, pried the

door open. As we entered, something swayed. The feet dangled inches above the

floor. I stared at the bulging eyes and lolling tongue. Mucous was oozing from

the nostrils.

We tried artificial respiration, unsuccessfully, "He's happy now," someone

said.

Later, a letter was found addressed to the dead man's family. He apologized

for "Dying ahead of you, before it was my rightful time."

The time crawled on. As the agony continued, nine more of the group followed

the first suicide. I too was tormented by the thoughts of death. I felt I could

not live another day under the Pig.

But–the three months of basic ended. With flying school ahead, we were

granted a two day pass. My sojourn at home was a strange one. My wounds and

bruises caused Mother and my sister Tomika anguish. I was washing, just after my

arrival, when Tomika saw the lash marks on my back. Bursting into hysterical

cries, she repeated, "What have they done to my little brother?"

But most people considered me a hero. I said the patriotic things that I was

supposed to. One morning I went to my old high school and was greeted as though

I had already performed valiant deeds. I made a speech to the school, "I hope

that many of you will follow me." I said, forcing a smile.

Hours later the train was clicking toward Hiro Air Base and I was thinking of

my father's last admonition: ". . . . and if you should ever gain dishonor, do

not return to bring unhappiness and shame upon us. Live honorably and fight

gloriously for the Emperor. Should you die, I have a grave of honor prepared."

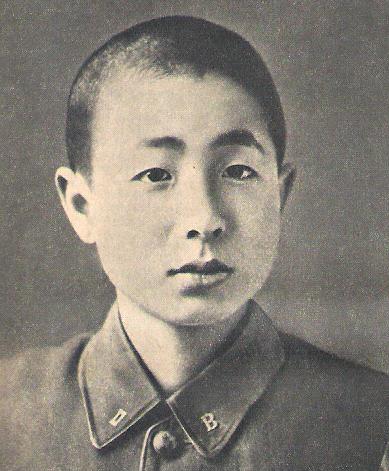

Yasuo Kuwahara. At 15, he had joined

the Jap Air Force. At 16, he was a Kamikaze.

(caption and photo from original article)

Flying school was better than basic, even though the punishment continued. We

had formed friendships and were becoming hardened–both physically and mentally.

We studied aeronautics and learned how to parachute. Within three months we

began flying the Akatombo (Red Dragonfly)–a small biplane with a forward cockpit

for the instructor and rear one for the student.

The new hanchos treated us no better than the Pig had. The worst was our

flight instructor, Namoto, whom we dubbed "Praying Mantis," because of his

gangly, insect-like appearance. He had an utterly vicious nature.

In basic we had been bewildered and terrified. During flying school, we

gained a spirit of defiance and began looking for revenge. Once we put dandruff

in Namoto's rice. Another time a wire tripped him so that he fell down a flight

of stairs, and still later we embedded 60 needles in his mattress.

For the wire trick he retaliated by running us six miles on a hot afternoon

in our feather-lined flying suits. For the needles he did stunts with us at high

altitudes–this time minus the flying suits and safety belts with the cockpit

open. The dandruff he ate, unknowingly, with gusto.

It was shortly after my solo flight that an inexplicable thing happened. We

were flying in formation when the Mantis commanded us to play follow the leader

with him. I was first in line close behind as he slipped into a bank, an easy

dive and began to loop. Pulling out of my own loop I came up almost on his tail.

For some reason, instead of slowing, I speeded up.

Namoto veered to the left and climbed into the sun. I followed, precariously

near. I was an automaton, obeying an outside force. The Mantis was screaming.

"Get off my tail, you madman! Drop back!"

He went into a steep dive and I followed as though attached by a cable.

Vainly he tried to escape, twisting, turning, climbing and diving. He could not

shake me. It was as though I wanted to strike him and crush him from the air.

We cut a tight left circle and the Mantis screamed. "Turn right! Turn right!"

I turned left and we missed colliding by a sliver.

Desperately the Mantis headed full speed for the mountains and soon we were

roaring between their shoulders, low along the valleys. His wing nicked off the

tip of a tall pine. Still I followed and we climbed, barely apart, till we were

above the first peak, circling.

Seconds later, the Mantis uttered a final, frantic oath and bailed out. I

watched the silken mushroom billow, snapping a doll-sized figure. Before it

reached the earth there was a flash a mile off. His trainer had crashed.

My brain was in a complete turmoil. I probably would have crashed somewhere,

had not a voice come over the phones: "Come back! Turn back! Don't do anything

you'll regret. Remember your family! Remember the Emperor!" It was an assistant

flight instructor, circling above me.

The episode, like a dream, had only lasted a few minutes, and I somehow

rejoined the main formation.

Later I was taken before the Commanding Officer, who questioned me.

I had nothing to say except that the Mantis had told us to follow him. I had

followed. The Commander was reasonable and only sent me to the guardhouse for a

few days, "to think things over."

It was not long before the Mantis visited my cell and beat me senseless with

a club. When I came to, I found myself covered with blood. The Mantis had used

his feet, too.

For four days he saw to it that I had nothing but pickles and cold rice. I

slept on the cement floor with one thin blanket.

On the second night I was wakened by a voice calling softly from outside.

"Are you all right? Put your head out. Let me see your face."

Thinking that a friend had come from the barrack, I pressed my swollen visage

partially through the bars and hissed, "Who is it?"

"It is I!" Something cracked, searing my face like a torch. Screaming, I

staggered back, throwing my hands up to my face. The Mantis had crouched there

with a whip. He leered from the shadows.

Before my release I was beaten on 15 separate occasions with a heavy, wet

rope, one lash of which usually knocked me out. With each beating he called me

names and said, "This is to teach you the value of a good airplane," or, "This

is to teach you that my life is valuable."

A day longer in the guard house and I definitely would have taken my life. I

knew how to do it. I would simply kneel, clamp my tongue between my teeth,

locking my hands on top of my head. Then I would slam my chin against the wooden

bench, bite my tongue off and bleed to death. More than one man died that way at

Hiro. But, somehow, the day of release came.

I was placed on latrine duty that week, and struggled along gritting my teeth

at every motion. I was afraid that I would be hospitalized, eliminating my

chances for fighter school. Graduation was near and we would be assigned

according to our aptitudes–fighter, bomber, signal or mechanic school. We all

wanted desperately to be fighter pilots.

Four fighter pilots were picked from my barracks. Luckily, I was one of them.

Tatsuno was another. I remember the Commanding Officer's graduation speech

vividly, because it was the first time I'd heard anyone in authority admit the

seriousness of Japan's situation. "Our future grows darker," he said in

conclusion. "It is for you, Nippon's Sons, to dedicate your lives and to die

valiantly."

During the next two months we flew training planes similar to our regular

fighters, though less powerful. This was our preparation for the Hayabusa 2, the

best army fighter then under production, outclassing the famous Zero.

The course was stringent, involving gunnery, formation flying, air maneuvers

and suicide practice [5]. The latter entailed diving

at the control tower from specified heights. This was the most difficult part of

flying because of the psychological effect–the idea that we were practicing to

die. The natural tendency was to complete the dive hundreds of feet above the

target. Eventually we developed a sixth sense which enabled us to feel the

ground coming up, and pulled out with less than 20 yards to spare at times. We

began to get an idea of what the real thing would be like.

And for the real thing we had not long to wait. Though the first air raid on

Tokyo had occurred over two years before, it was not until I started fighter

school that concentrated attacks on Hiro began. Even before we had finished our

training, we were sent up to defend the base.

Japan's fuel shortage prevented us from engaging the enemy in long battles,

even with our best fighters. Radar stations on our main island tips warned of

enemy approach. If their course was toward Nagoya to the east or Oita, the

opposite direction, we relaxed. If they headed for Osaka, between, we took to

the sky, fearing they might veer toward Hiro.

My first air battle occurred west of Hiro when five of us, flying Hayabusas,

were attacked by Grummans. A determined snout came at me from the rear, its guns

flashing. Instantly my heart jolted and my head and upper body seemed to run

empty, leaving my arms numb.

Whining, shredding noises. Magic holes appeared in my windshield and I cut a

sharp arc as he powered by. Seconds later I was on his tail firing, seeing the

burst go home. I was amazed that my body would even function and somehow felt

detached as though I were witnessing everything from another sphere. The lethal

buzz of motors, the staccato of machine guns and the blue white of the day sky

all had a dreamlike quality.

Mildly surprised, I watched the Grumman lose altitude, trailing a thin wisp

of smoke. Ramming my plane into a steep climb, I glanced back to see the pilot

bail out.

Just then a nasal voice said, "I am going to crash! The rest of you save

yourselves!" The voice was Lt. Shimada's, our leader. Just after he spoke, I saw

a flare of dazzling light and realized what had happened. Two planes, an

American and a Japanese, were falling as though they were toys cemented

together. I watched the crinkling water rise to meet the blackened fragments.

No more fighting for me. Wind whistled through the bullet holes in my plane

and with scant fuel I limped back for a landing. I had shot down an American

plane that day, but I had seen hundreds of others, and like other Japanese, I

knew that we must take desperate measures to survive.

Already, the Japanese had been pushed back all along the Pacific, and had

been almost eliminated as a strong naval power. We were losing confidence. An

indication of the changing attitude, men began surrendering more readily. At

first it had been only one Japanese captive to every hundred killed. Eventually,

however, small groups and finally whole battalions gave up.

Very gradually these facts were seeping through to the people. The scene was

swiftly being prepared when men like myself would appear–men who lived for the

single purpose of dying. This indeed was a telling indication of Japan's

desperate status.

Plans were already afoot for the use of Kamikaze pilots. A Col. Motoharu

Okamura of the Air Force had first suggested the idea to the Daihonei, the

Japanese high command in Tokyo, which had agreed. Okamura believed that 300

suicide pilots–each sinking a large American ship–could fan the winds in Japan's

favor. "I have personally talked to the pilots under my command," he stated,

"and I am convinced that there will be as many volunteers as necessary."

Officially, the suicide pilots went under the name of Tokkotai (Special

Attack Group), but "Kamikaze," named after the Divine Storm which swamped

Genghis Kahn's invading fleet in the 13th century, was more popular. Now, the

divine storm would have wings and the invader to be destroyed was America.

In October, 1944, the first Kamikaze pilot left his new bride to become the

world's first human bomb at Leyte Gulf. Within the next ten months, over 5,000

planes containing one and sometimes two men followed his lead [6].

The Kamikazes inflicted the heaviest losses in the history of the United States

Navy, scoring more than 2,000 direct hits on her vessels [7].

This figure included hits by the Baka bombs–low-winged monoplane gliders,

released from mother planes, which came into use toward the end of the war.

As the Japanese resorted more heavily to Kamikazes, the fighter pilots at

Hiro grew apprehensive. Kamikaze pilots were not born–they were selected from

our ranks. And as it became clear that the Kamikazes were devastatingly

effective, more valuable than fighter planes could ever be, we knew that we were

the next to be tapped.

It happened on New Year's Day, 1945, at Hiro. The Commander of the Fourth

Fighter Squadron called a special meeting. Solemnly he said, "The time has come.

We are faced with a great decision."

I felt it coming–the cold fear of imminent death. I recall his words vividly:

"Any of you unwilling to give your lives as Divine Sons of the Great Nippon

Empire will not be required to. Those incapable of making the sacrifice will

raise their hands."

Silence settled. Then, hesitantly, timidly, a hand went up, then another and

another . . . six in all. It was up to me. I could live! The Captain had just

said so. My hands remained at my sides, trembling. I could not raise them.

"So!" Captain Tsubaki eyed those who had responded. "It is good to know

exactly where we stand. Here are six men who have openly admitted their

disloyalty. Since they are completely devoid of honor, it becomes our duty to

afford them some. These men shall be Hiro's first attack group!"

So it happened that the first men from my squadron were picked for death. The

time was gone when men volunteered for such an "honor." They were picked and

Captain Tsubaki had gone about it in his own interesting way. The six who had

chosen life had been handed death.

How long, I wondered, would the Japanese people be able to hide behind their

immobile fašade? How many were true to themselves? Six had been true. They had

paid the price.

From that time on men were selected periodically from our squadron and

transferred to Kyushu for special suicide training. Most of us felt doomed. We

had only one straw to grasp. Perhaps the war would end. I think that more than

one man was guilty of praying that Japan would surrender. Many of the civilians

still had faith, but we who knew the facts had to be either na´ve or fanatic to

expect triumph. By February the enemy was attacking Iwo Jima, 750 miles from our

capitol.

Some of us had a little greater hope for survival than the rest, for we had

been rated as top pilots. The better pilots were saved as long as possible to

provide base protection. They also escorted other suicide missions, affording

defense and making reports.

Consequently, our poorest pilots died first, causing the Americans to

conclude, initially at least, that there were no skilled Kamikaze pilots. (The

American Admiral Mitscher put it differently. He said: "One thing is certain:

there are no experienced Kamikaze pilots.")

Orders from the Daihonei in Tokyo were sent regularly to air installations

throughout the four main islands, stipulating how many pilots each base would

contribute. Then men were committed to main suicide bases such as Kagoshima, the

largest, on the southern inlet of Kyushu, for final training [8].

Others, like myself, were trained at Hiro.

No one will ever comprehend the feelings of those men who made a covenant

with death. Condemned convicts don't even know the feeling. The convict is

paying for misdeeds and justice is meted out. The suicide pilot had done no

wrong. The philosophy that he was a "Son of Heaven," destined to be a guardian

warrior after death in the spiritual realms, didn't always provide solace.

Of course, there were fanatical Japanese fighters. Some wanted nothing but to

die gloriously. Generally, we pilots moved along two paths. The "Kichigai"

(Madmen) were fierce in their hatred, seeking honor and immortality. They lived

to die. Many of this type came from the Navy Air Force, which contributed a far

greater number of Tokkotai.

I belonged to another group, whose sentiments were frequently opposite,

though rarely expressed openly. Its members, mainly the better educated, were

referred to as "Sukebei" (Lotharios or Lovers) by the Kichigai.

Naturally, everyone's attitudes fluctuated. There were many times when I

wanted revenge. When I considered that by destroying an American ship I might

save many of my people, my own life seemed insignificant. But this was a feeling

I had to cultivate.

As the months faded, Japan began to stagger, losing her hold on eastern

China. The heart of Tokyo had been demolished and the entire homeland was being

laid waste. Millions of tons of our merchant shipping had been sunk and by April

'45, the enemy was assaulting Okinawa, Japan's very doorway. The island toppled

after 81 days of fierce battle.

By June '45, Hiro's airfield, hangars and assembly plant were being strafed

and dive bombed relentlessly by Grummans, Mustangs and light bombers. The time

came when 150 B-29's pulverized Hiro and nearby Kure Navy Port.

The warning had sounded 30 minutes beforehand and all pilots had taken off to

escape. After the bombing, there was no base to return to. I went to Oita on

north-eastern Kyushu. It was at Oita that I became a suicide escort.

Despite life's grimness, it was interesting to note individual reactions. The

physical torment of earlier days was gone. Tested and proved, we were the cream

of Japan's fighting airmen. We were given extra money and told to have a good

time during off hours. Men who had rarely touched liquor became drunkards.

Others, who had never even kissed a woman, joined the long lines before the

prostitute's door–10 minutes to a turn.

Several times a day I planned how I would make my death attack. I had it well

memorized. I knew the best way from having watched innumerable others succeed

and fail.

To a novice it might seem a simple matter to dive onto a ship. However, there

were factors which made it extremely difficult. There were the ever vigilant

enemy fighters. In addition, each vessel threw up an unbelievable barrage. The

combined output of anti-aircraft cannons, rockets and heavy caliber machine guns

created a lead wall. In addition, the ships always zig-zagged, so that a plane

coming straight down often found only a patch of water awaiting him.

The best procedure was to attack in waves of 15 planes at 30 minute

intervals. We would descend at anywhere from 10,000 to 5,000 feet, the sun at

our backs. The dive varied from between 45 and 60 degrees, leveling out at about

500 yards from the target, as close to the water as possible.

Thus, an approach was effected below the angle of the bigger guns. This low

attack was advantageous for another reason, for ships were frequently in danger

of hitting each other with their own ammunition.

Following the deaths of my twelve friends over Okinawa, and Tatsuno's

spectacular sinking of the tanker, I was ordered to report to the commanding

officer at Oita. He was obviously depressed. He had learned that, just after a

disastrous American air attack on an air field on Formosa, a Kamikaze pilot had

crashed his plane against one of the few remaining hangars, destroying 25 planes

[9]. At first it was thought to be an accident. Then

a note was discovered among the pilot's effects. He had deliberately destroyed

the hangar to prevent other pilots from dying!

"You see, Kuwahara, how conditions are . . . The time has come to put our

best pilots into the battle," he said, "Are you prepared?"

How long had I waited for this? At last it was coming. Strange relief and

emptiness. My voice seemed to come from afar. "Yes, Sir. I am honored to be

deemed worthy." I listened to what seemed a phonograph record of my own words:

"I wish to go as soon as possible."

"Your orders will come within the next week or two," he informed me.

"Meanwhile, you will return to Hiro."

The B-29s hadn't left much, but some effort had been made to restore Hiro's

life. Daily I waited for my orders, but time dragged by agonizingly–days, weeks,

an entire month. Still I hadn't heard, or seen anything in writing. August came

and I was still flying escort missions.

Early that month, we learned that some B-29s were flying southwest of Osaka.

They were expected to pommel Osaka, then split, striking Matsue and Okayama [10].

It was an indication of our fading strength that only four of us were picked

to lock with them over Kayama, approximately 30 minutes flight from Hiro. Having

calculated the time of contact with the enemy, I did some additional planning.

Our flight would carry us over Onomichi High School and near my home. This in

mind, I wrote a brief message to my family including my regards to the school.

Then I placed it in a metal tube with a white streamer attached. I had no idea

how many of my letters had been censored or had failed to arrive. At least I

could get them some sort of word before it was too late. I told them that I had

been picked as a Kamikaze. Over the school–near the familiar bay, shipyards, and

buildings–I dropped the message and saw the curious crowds waiting below to

receive it.

Then we flew on to Okayama. Right on schedule, the B-29s were moving

in–heading eastward at about 20,000 feet. There were only six of them, but they

were flanked by 12 Grummans.

I began breathing hard, feeling the wheel hard and cold in my clenched hands.

Our leader, a lieutenant, signaled and we began climbing. They weren't aware of

us until we had circled and dropped from the sun. As we began firing, the

Superfortresses cut loose with a vicious barrage and the Grummans swarmed into

action.

I followed the lieutenant, slicing down vertically–blazing at the second '29

while he concentrated on the first. Just before I completed my pass, I saw the

lieutenant's plane shudder. An instant later, he plowed straight into his target

and the two ships were instantly reduced to a yellow-orange burst.

Without thinking, I pulled out and for a second felt the blood leave my head.

When I came out of my daze, the remaining bombers had fanned and were swerving,

fearing the same fate as their leader.

During my second run, I dived at the trailing '29, saw my tracers arching,

appearing to curve–making contact I saw the big giant cough smoke and it was

then that a surge of elation swept through me like strong hands lifting me up.

I never did see the '29's actual death, however. She was losing altitude, but

still game. As I screamed past her massive rudder a third time, intent on the

kill, I got a terrific ripping from her tail guns. Several angry Grummans buzzed

after me. Pulling out, I circled, climbing. After completing a full 360 degrees,

I glanced up and back over my shoulder. A Grumman above me was banking so close

that I could distinctly see the pilot. The sun glinted on his goggles and his

white teeth flashed in a determined grin. A confident American. I'll never

forget that look, because it scared me, filled my veins with water. Somehow that

expression symbolized something with which Japan could no longer cope.

Outnumbered, I ran for it, diving for the ocean and pulling out precariously

near the surface. My pursuers didn't follow with their faster but less

maneuverable craft. By then, though, the remaining fortresses were laying their

bombs on Okayama and my fighting was over for the day.

Despite my morbid feelings, our luck had been outstanding. In addition to the

'29 destroyed by our suicide, two more were damaged. My victim had apparently

gone down, its crew bailing out over the inland sea.

My escort missions continued and toward mid-August [11]

I returned from a flight to learn that my sister, Tomika, had paid a visit to

the Base. She had read my message and tried her best to see me. I was grieved

that she had not been permitted to stay, but thought, "Maybe it's best this way.

Better that all relations be severed." Tomika had left me a remembrance–a lock

of her hair. For a long time I sat, just holding it in my palm.

The next day I learned that my mission would fall within the next week. The

time had come but now it seemed almost anticlimactic. In a way I almost looked

forward to it. Death at last. Someone would be escorting me for a change. Still,

I held to those last days as a man clings to a slippery ledge.

August 6, I received a two-day pass–the final and sure sign that my death

date was close. A two-day pass. Such was the Japanese Military's kindness and

magnanimity to its fated sons.

At first I decided not to take the pass at all, thinking it would be better

not to see family or friends. But the pull of home was too great. An

overwhelming urge to return filled me, and I started out for Onomichi.

I would be with the people I loved. There would be no talk of the future.

Suddenly I felt that for two days I could find a peaceful island in life, a

final one, but a good one. Two golden days. Perhaps when it ended, I would

accept death. Perhaps death, as the poets had said, would be sweet. Maybe if

there were a God, He would make it easy for me.

Before returning home, I stopped in Hiroshima to visit a friend stationed at

the Second General Army Headquarters [12]. I left

the army truck at approximately 7:30 a.m. and several minutes later boarded a

street car. I left it and began walking along Shiratori Street. The sky was

slightly overcast and it was already growing sultry. Several people said good

morning and an old woman stopped me to ask why our fighters were no longer

appearing in the skies.

Moments later, I heard the air raid sirens. A small concern to me since two

planes had already passed over while I was on the street car. The lone '29 above

scarcely seemed worth considering at first. Several times, though, I glanced up.

There was something a little too placid about the slow droning. Something . . .

When I was approximately 2,000 yards from the General Headquarters, a tiny

object fell from the silver belly above. No bigger than a softball, it gradually

materialized into a parachute. Speculations were being made:

"What are they up to now?"

"More pamphlets?"

"Yes, more propaganda–more of the same old thing."

All other mutterings were cut off. Suddenly a monstrous multicolored flash

bulb went off directly in my face. Something like concentrated heat lightning

stopped my breath. A blinding flicker–blue, white and yellow. I threw up my

hands against the fierce flood of heat. A mighty blast furnace had opened from

the earth.

Then came a cataclysm which no man will ever describe. It was neither a roar,

a boom or a blast. It was a combination of those things with something else

added–the fantastic power of earthquakes, avalanches and floods. For a moment

nature had focused her wrath on the land and the crust of the earth shuddered.

I remember being thrown to the earth near the side of the house. Darkness,

pressure, choking and the clutches of pain. At last, a relief as though my body

were drifting upward. Then nothing.

When I woke, I had no idea how long I had been unconscious. As my senses

began functioning I found myself under a mass of debris. My legs were pinned but

I worked my arms to clear some of the litter from my face. My eyes, nose and

ears were clogged with dirt. For several moments I choked and spat. Searing

pains traveled through my body and my skin felt badly scorched.

I opened my eyes and it was some time before they cleared enough for me to

see the tiny spot of daylight overhead. I could hear more rumbling noises and

footsteps. "Help me!" I forced the words with all my strength. They were like

the croak of a frog. Again and again I called only to end gasping in despair.

The pressure was becoming unbearable.

Hours seemed to elapse. I called again. Gradually a numbness settled and I

began trying to visualize what had happened. A big bomb. The Americans had

dropped a new bomb. Was it the atom bomb? While flying I had received repeated

radio warnings from the enemy in Saipan. They had told us to surrender, stating

that the greatest power the earth had ever known was to soon be unleashed on

Japan.

How ironical the situation seemed! I could die where I was and no one would

ever know exactly what had become of me. A suicide pilot dying on the ground

only minutes from home. Such an ignoble way to die! I almost laughed.

Perhaps no one would ever dare approach Hiroshima. Maybe all of Japan was

gone. What a thought–no more Japan! No, of course not, I was dreaming. Suddenly

I gave a start.

Dust had sifted through the hole and there were sounds. I yelled with all my

strength. No answer. I yelled again.

"Be patient," a voice came. "I'm removing the boards!" Wonderful words. As I

waited, the thought came that perhaps I'd been there for days.

Sounds increased–more voices. Finally the weight was lifting, darkness

changing to light.

"Are you all right?" voices came. "Easy, easy–better not move!" But I began

to get up while the whole world teetered. What a weird, swirling vision–I fell.

Arms caught my body and lowered it to the earth.

"What happened?" I rasped.

"We don't know. A new enemy weapon. Maybe it was an atomic bomb."

"You'll be all right," another intoned. "Just stay here until you regain your

strength. No broken bones. You'll be all right."

They were soldiers from the army hospital, and they started to go. "Wait!" I

became frightened. "Don't go!"

"We must," came the reply. "Hiroshima is in ruins. Everyone is dead or

dying."

I learned that I had been buried for nearly six hours, from 8:15 a.m. until

2:00 p.m. It was impossible to determine the extent of my injuries, but after

thirty minutes in the open air I felt better. As I stood swaying, my vision

improved, opening a nightmarish spectacle.

People have attempted to describe Hiroshima after the atomic blast on that

fateful August 6, 1945. No one has completely succeeded. What happened was too

far beyond human experience.

Certain broad pictures burn as vividly in my mind today as they did

then–scenes of a great metropolis reduced to a fiery rubble pit while 129,558

human beings were killed, crippled or missing, all within the few ticks of a

watch.

An odd black rain was settling and I realized that my directions were gone.

About me, the land was leveled. Cries, groans and wails emanated from

everywhere. Unbelievable! My vision was still too blurred to discern people

distinctly.

Shiratori Street was buried with houses, folded and strewn like trampled

strawberry boxes. Bodies were all about. In the distance, the stronger buildings

still stood, charred and skeletal, some of them listing, ready to topple. Fires

rampaged.

Groggily, I gazed through the filter of grey at a sick sun, then at the

ground where I'd been buried. Vaguely I realized that fate had taken a turn in

my favor. A cement water trough used in case of fire, about the size of an

office desk, had stood against the house opposite the blast. Falling directly at

its base, I had lain in a pocket that formed a right triangle, partially

protected from the collapsing walls. Simultaneously, the walls had shielded me

from the explosion, heat wave and radiation which had turned grass nearby to

ashes. Some of the concrete had actually melted. Sand and mortar had settled in

the trough, forcing it to overflow. The remaining water had utterly evaporated.

A quick personal examination indicated eyes badly swollen, skin on my hands

and arms baked, a bruised right calf, cuts and contusions.

I hobbled slowly off and within a short distance found a pile of bodies. One

or two people were alive, struggling to get free. A body rolled from the heap

and a head emerged. The face was covered with cuts and its single eye blinked at

me. The nose was gone and the mouth writhed soundlessly.

"Here, here, I'll help you," I said and began removing the cadavers. I tugged

at a dead arm and fell backward. The flesh from the elbow down had sloughed off

like a baked potato peeling in my hands, leaving the glistening bone.

Battling nausea, I continued my task, freeing the prisoner. A few people

assisted but others merely looked on futilely. The moaning about me increased

and I moved on.

Within a few seconds I saw a man whose lower half was pinned beneath a beam.

Half a dozen people were grunting, and prying with levers. As they dragged him

free, blood gushed from his bowels and he died. His hips to his ankles had been

mangled, but the beam's pressure had prevented external bleeding.

Dazed, I continued. People were moving like half frozen insects, holding

their bodies or clasping their heads. An extraordinary number were naked. Some,

mostly the women, tried to cover themselves. Others were totally oblivious. I

realized that my own clothes were in tatters.

Once a woman called me. She lay on the ground, unable to rise. Attempts to

help her were useless, for my very touch caused agony. Her body was blistered

past recognition. Her hair had been burned to charcoal and not only the skin,

but layers of flesh were peeling from her like old wallpaper. One side of her

throat was scathed and laid open so that I could see the delicate filament blood

vessels pulsating with tortured blue life.

I stumbled on–lost. Innumerable forms appeared, all suffering from the same

hideous skin condition. Leper-like, they were falling apart.

Eventually I found myself before the remains of the Yamanaka Girls' High

School. At 8:15 about 400 girls had assembled in rows on the school grounds to

receive the daily announcements prior to beginning classes. Like a sickle in a

flower bed, the blast had laid them out, stripping off everything but their

belts. Watches, rings and buckles, the heat had embedded into their flesh. The

school medals worn about their necks were burned in between the breasts.

Many parents were examining the bodies. I watched a mother bury her face

against a father's chest, watched as her body racked with sobbing.

I saw expressions beyond grief and despair, heard the hysterical wails, saw

blank faces.

Efforts at identification were futile, for the young bodies were utterly

charred. Teeth projected–macabre grins in flattened featureless faces. Four

hundred girls, seared like hogs. The burned odor, like the combined smell of

fertilizer and fish, cloyed in my nostrils and I held my stomach.

Later, exhausted and in a state of shock, I was picked up by one of the

trucks from Hiro and transported to the base. As we neared the Ota River, I saw

people in throbbing blotches along the shores. Thousands sprawled along the

banks, their groans blending in an ominous dirge.

Countless numbers lay half in the water, trying to cool themselves. Some had

died that way, face down. The Ota was filled with living and dead. Many had

drowned. Corpses bobbed near the shore or washed along with the current.

Mothers, fathers, aged and infant–the bomb had used no discrimination.

During the following 36 hours I stayed at the Base. My skin had turned red

and smarted terribly. My eyes hurt and my body ached–a prelude to a lengthy

illness which left me bald for months and a radiation sickness which still

lingers.

At that time, more than any other, I felt a hatred for the Americans. Had I

been flying and spotted an American plane I would have done my utmost to crash

it. My life seemed of no importance.

When I returned to my barracks, several Kichigai were arguing with Sukebei

about the status of the war. Russia had declared war on Japan.

Since the bomb, all Tokkotai missions had been temporarily cancelled by the

Daihonei [13]. We were to do nothing until further

orders and each man felt a growing tension [14].

On August 14, a friend rushed into the barracks. He'd just returned from a

reconnaissance. "Kuwahara," he whispered. They say that Japan will surrender

tomorrow. The Emperor will announce Japan's surrender! The air is full of it."

At noon the next day officers and men were assembled in the Mess Hall before

the radio, mute as stones. Part of the delivery was static, but the rest was

audible enough for us to determine what was happening. The Emperor was

officially announcing the surrender of Japan!

His proclamation, like the atom bomb flash, left everyone stunned, and it was

an instant until the explosion occurred. I looked at the stricken faces, watched

the expressions alter. Suddenly a cry went up and one of the Kichigai leaped to

his feet. "Those American chikusyo (beasts)! May God condemn them! Revenge!

Revenge! What are we waiting for? Are we babies? Let us strike before it is too

late! We are expendable!" His gesture knocked cups crashing from the table.

"We are expendable!" rose the cry. A core of men sprang up and would have

rushed to their planes if the Commander had not intervened.

After we had returned to our barracks, motors groaned overhead–the screech of

diving planes, followed by two sharp explosions. We rushed forth to see flames

crackling on the airstrip. Sergeants Kashiwabara and Kinoshita had quietly

sneaked to their planes following the furor and became some of the first

Japanese to suffer death rather than the humiliation of surrender.

Other suicides followed. Several officers placed pistols in their mouths and

squeezed the triggers. Men committed harakiri, bit off their own tongues and

hanged themselves.

That same day, Admiral Matoi [15] Ugaki,

Commander of the Navy's Fifth Air Fleet, and a group of his officers became the

war's final Tokkotai. In a calm, fixed manner they taxied their Suisei bombers

down the strip at Oita and were last seen heading into the clouds for Okinawa.

The deaths at Hiro precipitated bitter arguing. Men of the Sukebei faction

contended that it was stupid to fight longer, that there was nothing to be

gained by dying. The Kichigai maintained that life would not be worth living,

that the Americans would torture and kill us anyway. The least we could do, they

said, would be to avenge the terrible crimes at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On the morning of the 18th, Hiro's Commanding Officer announced that the

propellers were being removed from our airplanes. All arms and ammunition except

enough for the guards were placed under lock and key.

The ensuring days were some of the strangest in Japan's military history. The

disparity which had so long existed between officers and men began to disappear.

Officers who had dealt unjustly with their men fled by night and were never

heard of again. Several of them were killed trying to escape.

Heavy guard was posted around warehouses and installations to prevent robbery

by military personnel and even civilians who ferreted through the fences.

Violence flared through the base. Kichigai and Sukebei bickered and carried on

gang wars.

It was on the 21st that I read the bulletin board near the mess hall: "The

following named men to be discharged, effective 23 August." Part way down the

list was, "Cpl. Yasuo Kuwahara."

It was as if someone had knocked the breath from me. Somehow I felt that it

was a mistake. But it was true–my discharge was soon confirmed on freshly cut

orders. It was true!

In two days I would be a free man. I couldn't believe it–that it would be

over. I still feared death. Wasn't it true that at Kochi and Oita airfield, they

had not yet taken propellers from their planes? And weren't efforts being made

by certain of the military to continue the war? The danger would increase if the

Kichigai elements became dominant. Secret meetings were held by both groups. I

was still awaiting a set of death orders.

More than ten years later I learned that on August 8, 1945, I was to have

been part of a final desperation attack, involving thousands of men and planes [16].

The great bomb which had killed so many of countrymen had saved me.

Despite my doubts and fears, the remaining days passed more calmly than I'd

anticipated. Early on the 23rd of August, I donned a new uniform. For a long

time I looked at myself in the mirror–at the golden eagle patches on my

shoulders. I was somehow looking into an unfamiliar face. It was the face of a

boy sixteen years old. I had grown young again. It was all over. All over! I

repeated the words endlessly.

The night before I left the base, a dozen of us–and close friends–dined on

sukiyaki in the billet of a Lt. Kurotsuka. There had been toasting with the sake

and each man had cut his own hand and drunk the blood of his comrade's in a

token of brotherhood [17].

Kurotsuka, an assistant commander for the Second Squadron, had been a peace

lover, but a valiant and beloved leader by all the men.

His final words to us were: "We have lost a material war–but spiritually we

are not vanquished. Let us not lose our spirit of brotherhood and let us never

lose the spirit of Japan.

"We are aged men in one sense. And yet we are very young and the future

stretches before us. It is for us now to dedicate ourselves not to death but to

life–to the re-building of Japan, that she may one day be a great power, yet

stand respected as a power for good by every nation.

"For what men, my comrades, in all this world, will ever know war as we have

known it? Or what men will ever cherish peace as we shall cherish it?"

The sake glasses were raised high.

Notes

1. The book indicates the date of the kamikaze

attack of Kuwahara's squadron as June 10, 1945 (Kuwahara 1957, 162).

2. A kamikaze pilot did not cut off an entire

little finger before his final mission, since this obviously would have made

piloting the plane much more difficult. There is no other published account of

such a practice. Often a Japanese pilot would send a lock of hair or fingernails to his

family.

3. The book does not indicate that kamikaze pilots

"had their last affairs" with these girls who gathered to see them off.

The book indicates that the girls gathered at Ōita Air Base (Kuwahara 1957,

147-9), not Kagoshima Air

Base as described in the magazine story.

4. The book describes Kuwahara's improbable escape

to Taihoku Air Base in Formosa (Kuwahara 1957, 157), but this article only

states he limped back to base, which most likely means Oita Air Base from where

he originally left to accompany the 12 men in the kamikaze squadron.

5. Air groups did not practice suicide dives even

before the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps was formed in October 1944. The first

kamikaze attack, which took place in the Philippines,

is not mentioned until later in the story.

6. The figure of 5,000 total kamikaze planes

between October 1944 and August 1945 is overstated. Yasunobu (1972, 171) puts

the total of Navy and Army special attack planes at 2,503. Some kamikaze planes

had three crewmen such as the Ginga bomber (Allied code name of Frances).

7. The figure of 2,000 direct hits by kamikaze

aircraft on US ships is overstated, but sources vary on the number of ships hit.

Rielly (2010, 324) states 407 ships were hit. Inoguchi (1958, 234) states that

kamikaze aircraft sunk or damaged 322 ships.

8. Neither the Army nor the Navy sent special

attack (suicide) squadrons to the southern island of Kyūshū for final training.

Instead, the squadrons were sent to these forward bases after they had trained

at air bases north of Kyushu, primarily on the main island of Honshū. Kagoshima

was not the largest suicide base. Actually, only 12 men in special attack

squadrons made sorties from Kagoshima Air Base during the entire war. On March 11, 1945,

the 12-man crew of a Type 2 Flying Boat made a sortie from Kagoshima as one of the

lead planes in the kamikaze attack by Ginga bombers on American ships

anchored at Ulithi Atoll. An American patrol bomber shot down the flying boat.

9. The book has a slightly different version of

the kamikaze pilot who crashed his plane into a hangar at a Formosa air base. In

the book, Kuwahara escapes to Taihoku Air Base in Formosa, and he witnesses this

incident (Kuwahara 1957, 160-1). In the story from Cavalier magazine,

Kuwahara returns to Oita Air Base, and the base commander finds out from some

type of communication about this incident.

10.The Cavalier magazine story mentions a

B-29 bombing of Okayama in early August 1945, but such an attack did not occur

in this time period. The B-29 bombing of Okayama took place on June 28-29, 1945

(Bradley 1999, 88-91).

11. The time of "mid-August" in the magazine

story is inconsistent with the book's chronology, which mentions August 1 as the

date of his last reconnaissance flight and his sister's visiting the base.

12. It is implausible that Kuwahara could stop

by unannounced to have a social visit with a friend who worked at the Army

Headquarters in Hiroshima.

13. In contrast to the story's statement that

all Tokkōtai (Special Attack Corps) missions were temporarily cancelled, they

continued after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Special attack planes that made sorties and did not return to base totaled 14 on

August 9, 14 on August 13, and 9 on August 15, mainly from Navy air bases at

Hyakurihara in Ibaraki Prefecture and Kisarazu in Chiba Prefecture (Hara 2004,

240-2).

14. When Kuwahara returned to Hiro Air Base

after the bombing of Hiroshima, the magazine story says that he and others on

the base were to do nothing until further orders, but the book states that he

made an unlikely two-hour reconnaissance flight over Hiroshima on August 8 to

survey the damage caused by the atomic bomb (Kuwahara 1957, 180-2).

15. Matoi is the incorrect given name for Vice

Admiral Ugaki. It should be Matome.

16. There is no evidence from other sources that

Japan planned a final desperation attack with thousands of men and planes to

take place on August 8, 1945.

17. Japanese people do not have any such custom

of drinking blood of another person in token of brotherhood. There is no other

published account of such a practice among Japanese airmen in WWII.

Sources Cited

Bradley, F.J. 1999. No Strategic Targets Left.

Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company.

Hara, Katsuhiro. 2004. Shinsō kamikaze tokkō: Hisshi

hitchū no 300 nichi (Kamikaze special attack facts: 300 days of certain-death, sure-hit

attacks). Tōkyō: KK Bestsellers.

Inoguchi, Rikihei, and Tadashi Nakajima, with Roger Pineau.

1958. The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II.

Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Kuwahara, Yasuo, and Gordon T. Allred. 1957. Kamikaze.

New York: Ballantine Books.

________. 2007. Kamikaze: A Japanese pilot's own

spectacular story of the famous suicide squadrons. Clearfield, UT:

American Legacy Media.

Rielly, Robin L. 2010. Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A

Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships, by Aircraft

and Other Means. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Yasunobu, Takeo. 1972.

Kamikaze tokkōtai (Kamikaze

special attack corps). Edited by Kengo Tominaga. Tōkyō: Akita Shoten.

|