When My Name Was Keoko

by Linda Sue Park

Originally published in 2002 by

Clarion Books

Yearling, 2004, 199 pages

Koreans suffered oppression when Japan ruled their country

from 1910 to 1945. When My Name Was Keoko, a young adult novel based on

the historical experiences of the author's parents, depicts the struggles of a

Korean family named Kim from 1940 to 1945 as Japanese repression became

harsher. Sun-hee and her brother Tae-yul, ten and thirteen years old

respectively at the novel's beginning in 1940, jointly narrate the story of

each family member's own covert efforts to resist Japanese rule. The novel's

title comes from the Japanese law forcing Koreans to take Japanese names. The

Kim family chose the Japanese name of Kaneyama, and Sun-hee and Tae-yul

reluctantly changed their names to Keoko and Nobuo, respectively. This novel

not only provides young readers insight into an often-neglected part of WWII

history but also vividly portrays strong emotional reactions to tyranny.

Linda Sue Park's historical novels have won much critical

praise. In 2002, A Single Shard, a historical novel set in 12th-century

Korea, won the Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to

American literature for children. In 2003, the American Library Association

selected When My Name Was Keoko as a Best Book for Young Adults and a

Notable Children's Book. These awards reflect Park's storytelling talent and

the thoroughness of her historical research. As Park explains in the Author's

Note at the end of When My Name Was Keoko, several stories in the book

come from her own parents' childhood experiences in Korea. Her mother, just like

Sun-hee, used the name of Keoko Kaneyama during Japan's rule over Korea.

Although the Kim family clearly hates the Japanese occupation, the author does

not demonize all Japanese people in the novel but instead presents Sun-hee's

Japanese friend positively and some Koreans negatively as they seek to profit

from the Japanese occupation.

Sun-hee and Tae-yul alternate as narrators of separate

chapters, and many times they both provide individual views of the same events.

They explain Korean customs and historical events in an easy-to-understand

manner that does not detract from the main story line. Tension fills the book,

as each member of the Kim family fears discovery by the Japanese

of their secret resistance to foreign rule. For example, the mother with the

help of her two children hides a small rose of Sharon tree, the national symbol

of Korea, despite Japanese orders to destroy them and plant cherry trees. The

atmosphere of fear intensifies when Sun-hee and Tae-yul witness girls sixteen

and older being forced one day to volunteer for work in textile factories away

from home without even the chance to return home to tell their families

goodbye. Park explains the Japanese use of comfort women in the Author's Note

at the end of the book, but the novel's narrative only hints vaguely at what

might happen to these girls.

The novel starts with the Kim family selecting Japanese names after being forced to register at

the local police station. The Japanese rulers have tried to wipe out Korean culture

by requiring schools to teach Japanese. They have banned teaching of Korean

language and history, printing of Korean newspapers, and conversing in public

in Korean. Sun-hee enjoys writing Japanese kanji and keeps a daily diary, but

her older brother Tae-Yul has much more interest in mechanical things

rather than academic pursuits. They both enjoy conversations with their uncle,

who owns a print shop, but he is forced to flee town because of his support of

the Korean resistance movement. Their father serves as vice-principal of

Sun-hee's school with the position of principal, like all top positions in

Korean society, reserved for a Japanese man.

|

|

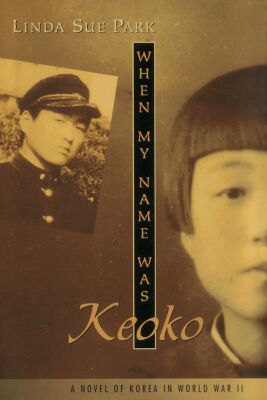

Cover of 2002 hardcover

edition published by

Clarion Books

|

|

|

|

Life for the Kim family becomes harder as the war

progresses. Food shortages lead to the family's eating millet rather than rice,

and the Japanese Army confiscates personal metal items for use in the war

effort. In early 1945, Tae-yul enlists in the Imperial Army and goes to Seoul

for training. He has always had a fascination with planes, and he also realizes

that families of Army volunteers receive better food rations and clothing. In

Tae-yul's seventh week of training, he volunteers for a special attack unit of

kamikaze pilots after he overhears Japanese officers talking derogatorily about

Korean soldiers' lack of bravery. When sent on a kamikaze mission from Japan,

he plans to miss the American ships, but his squadron has to return to base

when they cannot find any enemy targets due to heavy cloud cover. In the

meantime, the Kim family receives a last letter from Tae-yul written the day

before his mission. They believe he has died in battle, but they are overjoyed

when he returns home after the war.

Eleven Korean pilots actually died as kamikaze pilots in the

Army during the Battle of Okinawa [1], but the author's description of

Tae-yul's experiences as a kamikaze pilot contains a few inaccuracies. Park

used two supposed kamikaze pilot memoirs, Kamikaze by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon

Allred and I Was a Kamikaze by Ryuji Nagatsuka, to provide details for

Tae-yul's fictional experience in the Army, but some basic facts still differ from actual

history. Kuwahara's account later was determined to be fictional in the article

Ten Historical Discrepancies. Tae-yul entered the Army in early 1945 and would have had at most five

months of training prior to his kamikaze mission on June 20, 1945. Kamikaze

pilots actually required at least a year of training, including time for basic

training, flight training, and training for a specific type of plane. Tae-yul's

short time period seems even more unbelievable with only two training planes

for 200 men at his base and with training being carried out during a period of

frequent American air raids and lack of fuel.

Park used Nagatsuka's failed kamikaze mission [2] on June

29, 1945, from Kagohara Airfield near Tokyo for details contained in Tae-yul's

mission, although she changed the date and other details. Tae-yul's kamikaze

mission on June 20, 1945, occurs on a date in history when no Army special

attacks happened. During the Battle of Okinawa through June 22, both the Navy

and Army used air bases in southern Kyushu, not the Tokyo area, for kamikaze

attacks. Tae-yul writes in his last letter to his family that he has been

promised that it will not be censored, but this seems impossible since military

officers censored all correspondence from military bases. A letter written by a

Korean would be especially suspected. Nagatsuka writes in his memoir that he

got thrown in the brig for three days for failing to accomplish his suicide

mission [3], but Tae-yul's imprisonment lasts several weeks.

Young adults not only can learn Korean history and culture

but also can understand the value of freedom through reading this excellent

novel. Although the description of Tae-yul's experiences in the Army and a

special attack squadron lacks historical accuracy in several places, the rest

of the book reflects Park's thorough research and her parents' personal

experiences living in Japanese-occupied Korea during World War II. The actions

of Sun-hee, Tae-yul, and the other Kim family members reflect their courage and

love during Japan's attempt to eradicate Korean culture.

Notes

1. Muranaga 1989, 17.

2. Nagatsuka 1973, 179-99.

3. Nagatsuka 1973, 198.

Sources Cited

Muranaga, Kaoru, ed. 1989. Chiran tokubetsu kōgekitai

(Chiran special attack forces). Kagoshima City: Japlan.

Nagatsuka, Ryuji. 1973. I

Was a Kamikaze. Translated from the French by Nina Rootes. New York:

Macmillan Publishing.

|