I Was a Kamikaze

by Ryuji Nagatsuka

translated from the French by Nina Rootes

Macmillan Publishing, 1973, 212 pages

Some people wonder who could have written a book titled I

Was a Kamikaze, since the common perception is that all Japanese kamikaze

pilots died carrying out their suicide missions. Although no kamikaze pilot

survived crashing into an American ship, many others in kamikaze attack corps

survived. Some turned back due to bad weather or mechanical problems with their

outdated planes. A small number of escort plane pilots, who protected the

suicide attack planes, managed to escape the superior enemy fighters. Many Navy

and Army airmen, trained and ready for suicide attacks, disbanded after hearing

the Emperor's radio message to surrender. Ryuji Nagatsuka, a kamikaze pilot in

the Japanese Imperial Army, relates his experiences and feelings as he faced

death.

While a student of French literature at the University of

Tokyo, Nagatsuka entered the Army in 1944 as a cadet pilot. The book's parts

cover the three stages of his time in the Army. Part One deals with his basic

flight training, where he learned details of Japan's desperate military

situation. Part Two describes his training to fly fighters and his squadron's

two attempts to use their fighters to engage superior U.S. B-29 bombers. Both

times he returned with negative results for which he felt inexpressible shame.

Part Three relates his volunteering for the Special Attack Corps. He made a sortie with a group of eighteen fighters, but twelve returned to base because

bad weather made it impossible to locate the American fleet. The commanding

officer considered their action to be equivalent to desertion and a discredit

to the squadron, so the pilots were punched in the face, put under arrest for three

days, and forced to copy out the emperor's decree on military conduct.

I Was a Kamikaze was first published in France in

1972, and the English translation came out the following year. Surprisingly, no

Japanese version of this book exists. Since Nagatsuka wrote this book more than

25 years after the actual events, a few parts seem like he is looking back on

past events rather than describing his feelings and opinions at the time. For

example, when he first arrives at flight training school, the squadron leader

gives a long lecture of five pages filled with names and details of the war

situation. This speech appears to be more the results of the author's

subsequent background research for the book rather than what a brand-new cadet

pilot would remember. However, Nagatsuka's description of his suicide mission

has a real immediacy that will grip the reader. Before copying the emperor's

decree when put under arrest after returning to base, he secretly wrote in a

diary all of this thoughts during his two-hour flight.

A fascinating feature of this book is the depiction of the

author's conflicting emotions as he contemplates his impending death.

Nagatsuka's thoughts on death waver. At times he resolves that he will

willingly sacrifice his life for his family and countrymen, but at other times

he wants to continue to live rather than carry out a senseless suicide mission.

When he suffers contempt from the other men at the base after returning from

his suicide flight, he ponders the foolishness of the principle that a suicide

pilot should not return to base even though the only alternative would be to

futilely plunge into the sea without hitting an enemy ship.

|

|

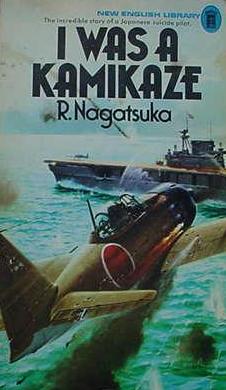

New English Library edition

|

|

|

|

In contrast to the commonly held image of kamikaze pilots

volunteering for suicide missions based on fanatical loyalty to the emperor,

Nagatsuka never thought of the emperor as the reason for his sacrifice. He

fought in whatever way he could, including joining a kamikaze special attack

corps, in order to protect his family and friends from the enemy. American

B-29s dropped incendiary bombs on Tokyo, his hometown of Nagoya, and other

major cities, killing tens of thousands of civilians and destroying hundreds of

thousands of homes. He willingly set out on a suicide mission for his family

and for his country's people, but certainly not for the emperor.

The author not only relates his history during the war, he

also provides his opinions, sometimes emotional ones, on several subjects for

which he does not have direct support or experience. For example, Nagatsuka states

emphatically that corporal punishment rarely occurred in the Army air force. He

rails against the "vile distortion of the truth" contained in a book

that described brutal physical violence committed by officers against cadet

pilots at Chiran, an air base in southern Japan from which many Army kamikaze

pilots made sorties. However, he never served at that base, and he also describes

his being punched in the face by a superior in a couple of separate instances.

The two Japanese characters (kanji) for "kamikaze"

(meaning "divine wind") can be read in two ways: "kamikaze"

or "shinpu." Nagatsuka speculates that nisei

(second-generation Japanese-Americans) in the U.S. military were the first to

use the pronunciation "kamikaze" to describe the special attack suicide

squads because "they did not know how to read Japanese correctly and so

pronounced the two Japanese characters for Divine Wind in a more vernacular way

[kamikaze]" (p. 142). He cites no support for such an assertion. Although

Shinpu was the official name given to the first unit formed in the Philippines

in October 1944, people in Japan both during and after the war frequently read

the two kanji as "kamikaze." The pronunciation "kamikaze"

was used frequently to refer to the "divine wind" that destroyed the

Kublai Khan's Mongol fleets invading Japan in 1281, so this pronunciation was

the most familiar one to Japanese people.

Nagatsuka's in-depth account of his fears and inner

struggles as he faces impending death makes I Was a Kamikaze a valuable

primary source to understand the psychology of the kamikaze pilots.

|