Leaves from an Autumn of Emergencies: Selections from the Wartime Diaries of Ordinary Japanese

by Samuel Hideo Yamashita

University of Hawai'i Press, 2005, 330 pages

Eight ordinary Japanese living during World War II in the home islands,

except for two men in the military who also served outside Japan, wrote the diary

selections included in this book. The diverse writers include two upper

elementary school students who evacuated to the countryside to escape fire

bombings of the large cities, a Tokyo housewife who had doubts early in the war

about the Japanese military's resources to wage war in scattered and distant

places, a Kyoto man in his mid-70s who had operated four billiards parlors but

by 1945 had only one open, an Army soldier in Okinawa who hid out in the hills

from the invading Americans until one month after surrender had been announced

by the Emperor, and a secretary in Tokyo who kept a record for her employer

while he served in the military. One diarist, Yasuo Itabashi, died in a special

(suicide) attack as a Kamikaze Special Attack Corps member on August 9, 1945.

Another diarist, high school student Shōko Maeda, worked

at Chiran Army Air Base in Kagoshima Prefecture for over three weeks to assist

special attack pilots in cleaning their barracks, doing laundry, and mending

clothes. Samuel Yamashita succeeds in his aim for the book, which is to

offer a "glimpse of how the war affected eight ordinary Japanese people and how

each responded" (p. 11).

The valuable 40-page Introduction discusses the following ten themes from the eight

diaries:

- Support for the war

- In 1943, complaints began about community councils and neighborhood

associations

- Political attitudes also changed in 1943/1944

- In 1945, home-front diarists began to lose confidence in armed forces

- Beginning in late 1944, unmistakable deterioration of home-front morale

- Social conflict and tension surfaced as Japanese lost faith in leaders

and morale sagged

- Began to contemplate defeat as early as 1944

- Japanese children readied for final battle that would decide fate of

homeland

- Willingness of Japanese servicemen to die

- Announcement of Japan's surrender came as complete surprise to only some

Japanese

Although the Introduction begins the book, it seems preferable to read the

diaries first so that themes can be identified by one's own examination of their

contents. The diary translations include footnotes that assist in understanding

the context and language. Many diary entries describe food shortages, especially

near the war's end, with common people barely able to survive on limited rations

and what could be purchased on the black market. Reading diary entries can be

unexciting, since sometimes references to events and persons are not clear, and

often the writing deals with rather mundane matters. Regardless, readers will be

rewarded by finishing these eight diaries by a much better understanding of how

normal Japanese people lived and thought during World War II.

Yasuo Itabashi's diary starts on February 18, 1944, the month when he left

the Japanese home islands for Pacific air bases such as Truk from where he flew

combat missions. Although he died in a kamikaze mission on August 9, 1945, his

last diary entry below is dated four months earlier on April 8 (p. 79).

April 8, 1945, clear

In the morning we practiced dropping thousand-kilogram practice bombs.

One bomb was twenty meters off the target, and a second misfired.

The engines of our planes were in great shape, and we

were in good spirits.

Preparations for the attack.

This time—I'm definitely not

expecting to return alive.

No, it's not that I don't expect to return

alive. I simply intend to body-crash, and thus my dying can't be avoided,

can it?

I'll get myself ready, write my last letters, and make

arrangements for the things I'll leave behind.

In the end, my life will have been twenty-two years

long.

I'll smear the decks of enemy warships with this

teenager's blood. It'll be wonderful!

The book includes the three last letters that Itabashi wrote in April to his

parents (shown below) and his siblings (pp. 79-80):

Parents,

Yasuo is happy and will go off to die laughing.

All I can do is aim my aircraft, and it may not be

something I can laugh about, but I expect to be laughing at the moment I

crash. In any case, please try to imagine this.

I wasn't able to do anything filial and apologize for

this.

Next, about my financial affairs, please use all my

money to pay the cost of constructing a plane.

Thank you for all the things you did for me.

I'll seem a complete stranger if I say this, but from

the bottom of my heart, thank you for your many kindnesses.

Japan definitely will win!

I will happily go off dreaming of the day of victory.

Please put up a good fight until the day of the final

victory.

Finally, I pray for my honorable parents' good health.

Good-bye

Attached to the

No. 1 Attack Air Group

Superior Flight Petty

Officer Itabashi Yasuo

Itabashi's diary presents several difficulties in truly understanding his

feelings about his wartime experiences, but the diary excerpt above shows that

he fully supported special attacks even though they resulted in death. The diary

entries generally do not give the location, which sometimes makes it difficult

to understand certain comments since he moved so many times between air bases

around the Pacific and Japan. Itabashi did not continue his diary for the four

months between the time he transferred to Kokubu Air Base in southern Kyūshū,

apparently for a special attack, and the time when he actually took off in

kamikaze squadron, so readers only get his initial reaction to the news of his

assignment and do not know whether his views changed. Itabashi's diary entries

have time gaps as long as several weeks, so at times they seem to jump abruptly between topics. In contrast, the diary of Seiki Nomura, the soldier who hid out

in Okinawa from enemy troops and did not realize the war had ended includes

entries almost every day from August 2 to September 14, 1945, which makes it

easy to follow his thoughts and emotions during this period.

According to the two diary entries below (p. 64), Itabashi was assigned to,

rather than volunteered for, a kamikaze squadron in the Philippines. Later diary

entries, only three between November 15, 1944, and January 3, 1945, reveal

nothing more regarding his reactions to this assignment to a kamikaze squadron

and explain nothing as to why he did not actually make a kamikaze attack in the

Philippines.

November 8, 1944, clear

[first paragraph omitted]

There are few pilots left. The division leaders flew

off to Kokubu Air Base. I went to the First Air Fleet Headquarters in

Manila, and my fate had been decided.

November 15, 1944, clear

I learned I'm in the same divine wind special-attack squadron as Second

Lieutenant Kunihara and Sergeant Asao Hiroshi, which surprised me.

The 503rd Air Group has been decimated. There are just

a handful of survivors. Like the others, I'll go off on a special attack.

Everyone wants to join his friends. I'm just amazed by the strange tricks

fate plays on us.

Itabashi's most serious reflection regarding his impending death in a special

attack is the following diary entry over three months after his assignment to a

kamikaze squadron in the Philippines (pp. 69-70):

February 22, 1945, cloudy, light rain

[first ten paragraphs omitted]

The day when I offer up my small five-foot frame is

approaching. When I catch up with my war buddies, I won't be late. I'll just

exhaust my death power and advance to annihilate the enemy. A sea eagle

[Navy pilot] wrote the following verse:

Though I don't regret my body's scattering,

My thoughts are on the future toward which the country moves.

The poem has a logic. I find it congenial. Yet what sort of state will

exist without victory? Will the Yamato people still exist if we're

completely defeated? We'll give up our lives for the sake of victory. Happy

and laughing, we go off to crash — one plane, one ship —

and there is nothing quite as powerful as the decision to die. What are

physical objects? One absolutely doesn't expect that things fashioned by

human hands can't be destroyed by human hands. When all is said and done,

victory resides in the self. This is simply a story of my giving up my life

to lead the way to victory.

The next month Itabashi volunteers for a special attack squadron, and the

following day he is transferred to an air base in Chiba Prefecture, but it is

not certain that the transfer came about based on his request (p. 72):

March 8, 1945, cloudy

In the morning I went to the Naval District Personnel Office, told them

my situation, and asked them to decide on my next assignment.

I telephoned the personnel office at the Naval Aviation

Department and requested a special-attack unit.

March 9, 1945, cloudy

In the morning I received an order to transfer to the No. 1 Air Attack

Squadron of the 601st Air Group at Katori Air Base. After lunch I finally

left my group.

[last two paragraphs omitted]

Itabashi's diary, which ends on April 8, 1945, never indicates specifically

that he became part of a kamikaze unit. However, the following entry may signify

that he will be part of a kamikaze unit, since Kokubu Air Base in southern

Kyūshū is one of the bases used for the first mass kamikaze attack on the

American fleet on April 6 (p. 79):

April 7, 1945, clear

At long last, we received the order we've been waiting, and hoping, for.

We'll go to Kokubu. The appointed day is the day after tomorrow.

Banzai! I'll do it!

This will be to avenge my several hundred war buddies

from the 503rd. I'll do it. I'll be decisive!

According to fifteen-year-old Shōko Maeda's diary,

the special attack pilots at Chiran Air Base treated her and her classmates with

kindness. On April 2, 1945, she writes, "Although the pilots themselves will

perish together with the enemy ships, they were cheerful as they talked to us,

worried about our futures, and warned us not to die in vain." She honestly

describes her feelings such as in the following sentence, "Miyazaki told us

stories about philosophy, but I couldn't understand what he was saying, and my

head began to spin" (p. 225). On April 12, her diary entry describes the

background for a famous newspaper photograph of Maeda and her classmates as they

waved branches of cherry blossoms at the pilots as they took off (p. 230):

April 12, 1945

[first paragraph omitted]

We picked as many cherry blossoms as we could and ran

back as fast as our legs would carry us, but the planes had gone to the

starting line and were about to begin taxiing down the runway. They were far

away, and we were sorry we couldn't run out to them. Motoshima's plane was

late and went to the starting line right in front of us. Then the squadron

leader's plane took off. It was followed by planes piloted by Okayasu, Yagyū,

and Mochiki. The Type 97 fighters wagged their wings from left to right, and

we could see smiling faces in all the planes. The plane piloted by Anazawa

from the Twentieth Jinbu [Shinbu] Squadron passed in front of us. When we

waved branches of cherry blossoms as hard as we could, the smiling Anazawa,

his head wrapped in a headband, saluted us several times.

Click! . . . when we turned and looked behind us, it

was the cameraman taking our pictures. When every one of the special-attack

planes had taken off, we just stood there for a long time, gazing at the

southern sky, which seemed to go on forever. Tears welled up in our eyes.

[last two paragraphs omitted]

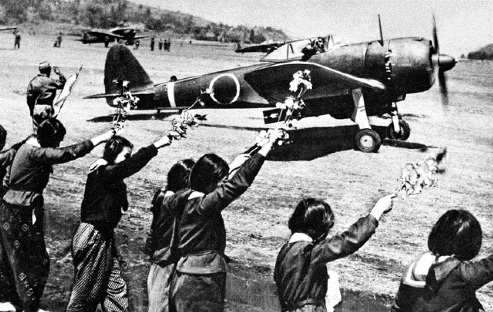

Chiran High School girls wave branches of cherry blossoms

at departing special attack pilot Toshio Anazawa (April 12, 1945)

The two chapters on kamikaze pilot Yasuo Itabashi and high school

student Shōko Maeda have several factual errors. Yamashita's

introduction to Itabashi's diary and a note on the chapter's last page state

that he took off on August 9, 1945, from Kokubu Naval Air Base on the southern

island of Kyūshū as a member of the No. 4 Mitate (Great Shield) Special Attack

Squadron and was killed in action in Kingazan Bay off Okinawa (pp. 51, 80).

Actually, he took off from Hyakurihara Naval Air Base, located in Ibaraki

Prefecture about 50 miles northeast of Tokyo and over 600 miles northeast of

Kokubu [1]. No "Kingazan Bay" exists in Okinawa, but

a Japanese source [2] indicates that Itabashi's squadron

died in battle east of Kinkasan (an island) in Miyagi Prefecture, about 1,100

miles northeast of Okinawa. Although Itabashi's next to last diary entry dated

April 7, 1945, indicates that he was going to Kokubu, and in April kamikaze

attacks were directed exclusively toward Okinawa where the American fleet had

invaded, four months later in August the American fleet had moved and several

sorties of kamikaze squadrons were made from air bases near Tokyo.

Yamashita's introduction to Itabashi's diary states that

his older brother Origasa died in a special attack in November 1944, but

Japanese sources that provide complete listings of men who died in special

attacks [3] do not mention Origasa Itabashi's name,

and even Yasuo Itabashi's diary entry dated November 28, 1944, does not mention

that he died in a special attack, "I heard from Superior Flight Petty Officer

Nishide, just back from Manila, that my older brother Origasa died recently in

an attack on an aircraft carrier" (p. 65). Most likely Origasa Itabashi died in

a conventional air attack. Yamashita also states that Yasuo Itabashi "saw action

for the first time" in 1943 when "training at several air bases in Kyushu" (p.

51), but it is unclear what this could refer to since the Allies did not attack

the Japanese mainland directly until the following year other than the Doolittle

air raid on Tokyo in April 1942.

The translation of Maeda's diary uses the name Jinbu

Squadrons to refer to the Army's special attack squadrons that took off from

Chiran Air Base, but the correct spelling is Shinbu Squadrons. Maeda's diary

entry on April 12, 1945, mentions that the 20th Jinbu (should be Shinbu)

Squadron had Type 97 fighters, and a footnote incorrectly states that these were

Nakajima B5N1 Type 97 Carrier Attack Bombers, which the Allies called the "Kate"

(p. 230). This was a Navy plane, so Army pilots from Chiran would not be flying

such an aircraft. The 20th Shinbu Squadron members carried out their special

attacks in the Nakajima Army Type 97 Fighter (Ki-27), nicknamed Nate by the

Allies.

Shōko Maeda, first row right, and

two classmates in spring 1945 (p. 223)

Notes

1. Hara 2004, 241; Osuo 2005, 231.

2. Hara 2004, 241.

3. Hara 2004, 138-9, 144-51;

Osuo 2005, 160-66.

Sources Cited

Hara, Katsuhiro. 2004. Shinsō kamikaze tokkō: Hisshi

hitchū no 300 nichi (Kamikaze special attack facts: 300 days of certain-death, sure-hit

attacks). Tōkyō: KK Bestsellers.

Osuo, Kazuhiko. 2005. Tokubetsu kōgekitai no kiroku (kaigun

hen) (Record of special attack corps (Navy)). Tōkyō: Kojinsha.

|