|

|

|

|

Ryōji Uehara (right) on day before sortie from Chiran

Airfield. Next to him is Eiji Kyōtani, also a 56th Shinbu Squadron member.

|

|

|

Last Writings: Hero, Dying in Vain, Reality That Cannot Be Expressed by

Dualism (Isho: Eiyū, inujini ni, nigenron de katarenu jissō)

Researched and written by Shūji Fukano and Fusako Kadota

Pages 358-362 of Tokkō kono chi yori: Kagoshima shutsugeki no kiroku

(Special attacks from this land: Record of Kagoshima sorties)

Minaminippon Shinbunsha, 2016

At Azumino in Nagano Prefecture where abundant fields spread out among the

heart of the mountain peaks of the Northern Alps, there is a monument to Ryōji

Uehara (age 22 at death), an Army Second Lieutenant who died in battle off

Okinawa as a member of the Army 56th Shinbu Special Attack Squadron, which took

off from Chiran Airfield in Chiran Town (now Minamikyūshū City)

on May 11, 1945.

Ryōji was born in Ikeda Town. On the monument, there is inscribed an

excerpt from Shokan (My Thoughts), his last writing that was written and left

behind at the request of news crew member Toshirō Takagi (now deceased) on the

night before the sortie of Ryōji who had joined the Army in December 1943

as part of the student mobilization while he was studying economics at Keiō

University.

"I think liberty's victory is evident." "Although authoritarian and

totalitarian countries may prosper temporarily, it is certainly a plain fact

that they will be defeated in the end."

Japan in those days was steeped in totalitarianism where it was natural for

citizens to give their lives for an "eternal cause" in support of the Emperor

and country. Uehara's distinctive last writing, where he proudly expressed his

opinion as a liberalist, criticized as a traitor or as unpatriotic, was

published at the beginning of the revised edition of Kike wadatsumi no koe

(Listen to the voices of the sea), a collection of writings of Japanese students

who died in war.

"As for me, who is a machine, there is no right to say anything. However, I

only wish that the Japanese people will make my beloved Japan great."

Ryōji, instead of accepting his own absurd death, called for citizens to

realize a new Japan that would preserve its various values. In 2006, the

monument to Ryōji was erected by local volunteers to tell future generations

forever about his thoughts.

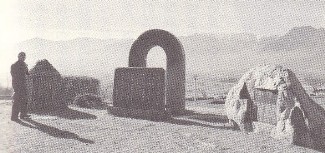

Ryōji Uehara Monument on hill that

looks out on magnificent scenery of

snow-capped Northern Alps and Azumino

Next to Ikeda Town is Hotaka, where Ryōji spent his adolescence. Hiroaki

Nakajima (age 81), a local history researcher who lives in Azumino City, started

a new job as a teacher in 1983 at his alma mater Matsumoto Fukashi High

School in Matsumoto City. At that time he learned that Ryōji graduated from

this school's predecessor, Matsumoto Junior High School under the prewar

education system. He was shocked by Shokan (My Thoughts).

Although Ryōji was a Special Attack Corps member, in what way were such

independent thoughts fostered? From that question Nakajima analyzed in detail

three last writings, which Ryōji left behind by the time of his sortie,

and six types of diaries. He collected testimonies from his younger sisters and

friends, and he explored the process of formation of those thoughts. He put

together the results in 1985 in a book entitled Ā, sokoku yo koibito yo

(Ah, My Country, My Sweetheart).

Ryōji was born as the third son in a family with five children. He had two

older brothers and two younger sisters. His father Toratarō, who was a

practicing doctor, had the following educational principle, "Express your own

thoughts and what you want to say before anyone without hiding anything." He

grew up in a cultured family environment where all family members were fond of

music. Incidentally, his two older brothers who had become military doctors did

not return from the battlefront. The Uehara Family lost all of their three

male children.

Nakajima says, "His grandfather who had significant involvement in

Nagano's Freedom and People's Rights Movement and Ryōji's attendance at

Matsumoto Junior High School and Keiō University, which had independent academic

traditions, shaped his knowledge as a future liberalist."

When Ryōji entered the military, there still was

totalitarianism. In September 1943 when draft deferment was abolished, his first

farewell note that listed his favorite books had these words, "I believe firmly

that serving the country directly will repay indirectly my parents' kindness."

The tone is not that different than a typical soldier in those days.

In his second farewell note, which seems to have been written while

he was in flight school from February to June 1944, he made clear his spirit as

a liberalist, "Liberalism is needed in order for Japan really to continue on

eternally. In Shokan, his third farewell note, he reached the point of

urging the Japanese people to awaken to liberalism.

Nakajima points out, "What opened the bud of liberalism within Ryōji was

the military's absurdity where he was trained to be a 'machine' without feelings

that was robbed of human dignity. That can be seen by looking carefully at his

farewell notes and diaries."

Nakajima realized that in Shokan Ryōji properly used points of

view by precisely distinguishing between first person watakushi (私),

second person wareware (我々) and gojin (吾人), and third person

kare (彼) and liberalist. Gojin, which means watakushitachi

(we) (the same as wareware), was used when Ryōji makes his strongest

declarations in the following two places: "Liberty certainly will be

victorious." "I wish that the Japanese people will make Japan great." [1]

Nakajima comments, "Isn't it that gojin was used with the

understanding that he represented the Special Attack Corps members who could not

object. Ryōji's way of thinking certainly was not unusual, and he suggests

that this thinking was shared by many student soldiers.

Volunteered or coerced? Hero or dying in vain? Until now there has been a

tendency for special (suicide) attacks to be spoken about in terms of an

easy-to-understand dualism. Nakajima questions this, "Have we endeavored to make

our way through the inner thoughts of Corps members one by one and to read and

understand each one's thoughts through what is contained between the lines of

their last writings?" He says, "A uniform way of viewing their thoughts only

leads us further from the truth about special attacks. Even after Special Attack

Corps members' deaths, it has turned out that they are viewed together as

'machines' in the military."

Hiroaki Nakajima

Note

1. This paragraph has been translated literally,

but it appears that the author's use of second person point of view actually means first

person plural (i.e., wareware, gojin, and watakushitachi,

which mean "we").

Related Web Pages

Translated by Bill Gordon

November 2024

HOME >

Stories >

Last Writings: Hero, Dying in Vain, Reality That Cannot Be Expressed by Dualism

|

|