|

|

|

|

|

|

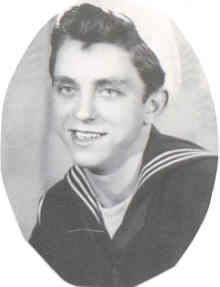

Joe Curgino

Seaman First Class

|

|

|

Little Italy to Okinawa

by Bill Gordon

Joe Curgino, a recent 18-year-old high school graduate who

had never been outside Chicago, entered the US Navy on April 10, 1944. He took

a short train trip with his family from their home in Little Italy, in Chicago's

Near West Side, to Great Lakes Naval Training Station, just north of Chicago

along Lake Michigan. Although he would be near his home for five short weeks of

boot camp, his mother especially worried when her oldest son of a family of two

sons and five daughters would leave the country to fight overseas. The war had

already brought changes to this close-knit family. The children used to attend

Italian language lessons on Saturday afternoon at Mother Cabrini School, where

the nuns even taught the singing cheer of "Viva Mussolini!" to the

students, but these lessons ended abruptly in December 1941 when Italy declared

war against the United States.

One morning in May 2006, my wife and I visited Joe Curgino

and his wife Rose at their spacious split-level home in Bloomingdale, a

northwest suburb of Chicago. Rose also grew up in Little Italy just two blocks

from Joe's home. They wrote letters to each other while he served in the Navy,

and they married in 1949 after a seven-year courtship. This morning Joe agreed to

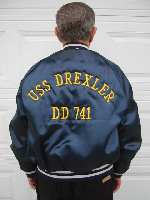

tell us about his service aboard the destroyer USS Drexler (DD-741),

which sank off Okinawa after being struck by two kamikaze planes on May 28,

1945.

Joe and about 60 men, who after completing basic training at

Great Lakes Naval Training Station, went next to the naval base at Norfolk,

Virginia, for training to be part of the crew of a destroyer being built at

Bath Iron Works in Maine. He hated cooking duty in the mess hall, but he still

did his best for the chief cooks. He marveled at Norfolk's many bright stars,

which he had never really seen before due to bright lights in the Chicago area.

About 20 crewmen, including Joe, went to Maine in order to pick up their 376

ft. 6 in. destroyer. He marveled at the many women working hard doing welding

and riveting of ships at Bath Iron Works. They took the ship to Boston Navy

Yard, where the USS Drexler was commissioned on November 14, 1944, with

about 350 officers and crew.

|

|

|

Joe Curgino proudly wears

his USS Drexler jacket

|

|

|

|

Drexler went on a shakedown cruise to Bermuda, where

Joe for the first time away from home spent a lonely Christmas holiday thinking

about family and his mother's delicious Italian cooking. After the destroyer's

crew completed a multitude of training exercises, the ship went to Boston and

Norfolk for repairs and supplies. Back in Chicago, Joe's concerned family had

visited the local Red Cross office to inquire as to why they had not received

any letters from him, but eventually letters arrived that he had been doing

well. Drexler proceeded without delay to the Pacific battlefront via the

Panama Canal, San Diego, San Pedro, and Pearl Harbor.

Joe as Seaman First Class was in the gunnery division and he

had training and assignments on both 5-inch and 40-mm guns. His final post was

at the Mount 42 twin 40-mm guns on the port side. The mount's gun captain

coordinated six men to load, point, and fire the guns. He remembered his

girlfriend both by the photo he carried and by her name "ROSE"

painted on the barrel of his gun. Gunnery Officer Chet Lee, who later went on

to become mission director for six Apollo missions including Apollo 13, always

kept his division busy with drills since a destroyer's guns needed to shoot at

land targets, planes, strayed mines, and other ships.

On February 23, 1945, Drexler departed Pearl Harbor

for Guadalcanal and then on to Okinawa for the invasion of the Japanese island.

Joe was amazed at the huge number of warships, including about 16 to 18

carriers, from horizon to horizon just a day or two before the invasion of

Okinawa on April 1. While the land battle raged on the island, Drexler

served at several radar picket stations to protect the main fleet from Japanese

air attacks and also participated in the occupation of Tori Shima, a small

island north of Okinawa. During the early morning on May 28 while Drexler

was at Radar Picket Station 15 about 45 miles northwest of Okinawa, Joe heard

the warning that the ship's radar had picked up a squadron of eight approaching

bogeys (enemy planes).

A handful of combat air patrol (CAP) planes went after the

Japanese squadron, but the first kamikaze plane came in from the starboard

side, crashed into the destroyer at midship near the waterline, and cut off all

power. Although Joe on the port side just glimpsed the incoming kamikaze plane,

he felt the crash jar the ship and went to manual control on his gun mount

since both regular and emergency power had been knocked out. A second kamikaze

plane approached a few seconds later, but it was splashed with direct hits from

one of the ship's 5-in. guns. A third

kamikaze followed closely by a Corsair fighter, passed directly over Drexler,

but the smoking plane recovered just over the water and then banked to come in

at the destroyer from dead ahead in a shallow glide. The plane passed just over

Joe's head and crashed into the port base of the #2 stack.

Nobody gave orders to abandon ship, but the men realized

that they needed to jump as the ship started rocking strongly after the second kamikaze plane crashed into Drexler. Joe went quickly down a ladder from

the gun mount to the lower deck. The ship began listing very fast to its

starboard side. Joe quickly began walking toward the keel of the ship until he

had to jump off into the water. His life flashed in front of him as the sinking

ship's descent pulled him deep into the water. As he broke the surface amidst

fire and oil, he looked right and saw the "741" painted on the ship's

bow disappear into the water. He then looked left and glimpsed his two Italian

buddies Daiuto and Devito for the last time with their arms wrapped around each

other.

A large life raft floated at some distance from him, so he

started swimming under the flames and oil toward it. Although he had no time to

put on a life jacket, he made it quickly to the raft since he had always been a

good swimmer. He was the second man to reach the raft, and he climbed into it

in a daze. The life raft began to be swamped as more men came aboard, so the

coxswain tried to calm the panicked men and ordered those men without wounds

into the water around the raft, where they held onto the sides or onto a rope

attached to the raft. The men floated on their backs to minimize any injuries

if Drexler's depth charges or boilers exploded. The coxswain went back

to save others in the water, but Joe and the other men clinging to the raft

never saw him again.

The men around the life raft remained in the water for well

over an hour until an LCS (Landing Craft, Support) ship picked them up. When

the raft first approached the LCS, it appeared that the ship moved away but

this could have been because Japanese planes still remained in the area. The

LCS crew threw a rope ladder down the side of the ship. Joe's hands froze on

the rope ladder, and a crewmember had to pry his clenched hands from the rope

in order to get him onto the deck. The LCS also picked up a few wounded men

from the destroyer USS Lowry (DD-770), which had helped Drexler

fight off the kamikaze squadron that had attacked the radar picket station. The

officers and crew from Lowry lined the decks and saluted the men leaving

on the LCS in order to pay their respects.

|

|

|

|

|

Painting of Joe Curgino

done by art teacher at

his grandson's elementary school

|

|

|

The non-wounded Drexler survivors made their way back

on three different ships to Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. Drexler's

Executive Officer talked with some of the crewmembers, including Joe, and asked

whether they were ready to go to another ship. Everyone responded "no

thanks" in not such polite terms. While serving his tour of duty on Drexler,

his weight had dropped to 118 lbs. from his normal weight of 135 lbs. Navy

doctors wanted to send him to Warm Springs, Colorado, for rest and

recuperation, but he successfully pleaded with them to go back home to Chicago.

Reports of the sinking were read back home, but the family was unable to find

out what had happened to Joe. He got off the bus at Loomis and Taylor Streets

in the heart of Little Italy, and he began walking the short distance to home.

The neighbors recognized Joe and yelled greetings to him as he walked down the

street. His brother Jim and his sister Mary ran down the street to hug him.

After arriving home, his mother and father cried with joy that their oldest son

had returned home.

The Navy provided each survivor of Drexler's sinking

with a 30-day leave. He did not see Rose on his first day home since he was not

in good physical shape, but he enjoyed seeing her many times during his leave.

With Joe's mother serving him Italian home cooking every day, he quickly gained

30 pounds. Shortly prior to the announcement of Japan's surrender (within a few

days of the war ending), Joe reported for reassignment to active service at the

Naval Armory in Chicago. Days later, Joe was reassigned to Navy Pier in

Chicago. Then shortly after that, he was reassigned to St. Louis where he

worked at the Separation Center at Lambert Field. There he had the chance to

attend a couple of baseball games where he could root for his favorite Chicago

Cubs against the St. Louis Cardinals.

After many months at Lambert Field, he was reassigned to Glenview Naval

Air Station in a suburb of Chicago. He had a bus accident while stationed

there, so he thought he would receive a reprimand for it when called to see the

admiral. However, the admiral surprised Joe with a personal presentation of a

Letter of Commendation that was awarded to the men of Drexler for their

bravery. Then he was sent to Great Lakes Naval Training Station for discharge in

June 1946. Even with his admirable service record aboard Drexler, he

never received his final paycheck from the Navy despite repeated inquiries.

Although Joe had told his family many times the story of Drexler's

sinking and other incidents in the Navy, he never had the chance to tell the

history of his naval service from beginning to end until this morning in May

2006. Even though over 60 years had passed, he vividly remembered the details

of the sinking. Deep emotions still remain from the traumatic event. While

telling his story, he paused and wept a few times such as when he recalled the

deaths of his two Italian friends, the salutes by the men of destroyer Lowry

to pay respects to Drexler survivors on the LCS, and the warm homecoming

greeting by his family. As he talked, he made the sign of the cross several

times to show his gratitude to God for allowing him to survive and his

remembrance of 158 Drexler shipmates who died in the sinking.

Before my wife and I left after the

interview, Joe and Rose took us on a tour of their home and backyard. We

discovered how interested and actively involved their three children, Andrew,

Grace, and Roseann, and their five grandchildren have been in his story of

surviving Drexler's sinking. A pencil drawing of Drexler, together with

a brief history of the destroyer, hangs proudly in their family room. He told

us his son Andrew had an artist draw the ship and gave it as a gift. His

daughter Roseann contacted Bath Iron Works in Maine to obtain photos of the

destroyer’s construction as well as launch photos for the ship's history

published by the U.S.S. Drexler

(DD-741) Survivors Reunion Association. She also arranged to have the American

flag flown on December 7, 2001, at the USS Arizona

Memorial at Pearl Harbor in honor of her father and Drexler's crew. She

even wrote to President Bush in March 2006 to try to get the government to

officially honor Drexler's crew, but

there has not yet been a response.

In June 2001, Joe visited his grandson

Anthony Viola’s fifth-grade class at Oriole Park Elementary School on the

Northwest Side of Chicago. He spoke to the students about his wartime

experience, showed them photographs, and answered some good questions. He showed us a painting of him done by the school's art

teacher based on his wartime photographs.

Anthony's class later also sent him a poem signed by all the students to express

their thanks:

The class in room two-zero-nine

would like to share with you a

little rhyme

Thank you for visiting us

and coming to discuss

The memorable experience you had

you wonderful and precious

granddad!

May your past experiences make you

stronger

may you live a whole lot longer

Thank you for taking a trip down

memory lane

we're sorry you might have experienced

much pain

We send lots of wishes to you

we're glad you can tell your

stories from WWII

We understand your terrible

hardship

we wish your name could be on

another battleship

You showed us pictures of WWII

we offer a salute to you

It's too bad your belongings were left behind

but always remember you are

one-of-a-kind!

Please feel free to come back

and tell us another amazing

flashback

We don't want to say good-bye

because you are such a terrific guy

|

|

|