|

|

|

|

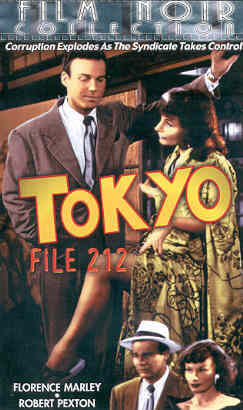

Videocassette Cover

|

|

|

|

|

|

DVD Cover (Alpha Video)

|

|

|

|

Tokyo File 212

Directed by Dorrell and Stuart McGowan

Cast: Florence Marley as Steffi Novak

Robert Peyton as Jim Carter

Katsuhiko Haida as Taro Matsudo

Reiko Otani as Namiko

Satoshi Nakamura as Mr. Oyama

VCI Entertainment, 1951, 84 min., Video

Jim Carter, an American Army intelligence agent, visits Japan undercover as a

journalist to try to disrupt a Communist group that is trying to assist North Korea during the Korean War. Tokyo File 212 was filmed entirely on

location in Japan during the American occupation, and many Japanese had

production and acting roles. The movie has many interesting shots including

street scenes, nightlife, train stations, Haneda Airport, a charcoal-powered

car, a geisha song, a street festival, and the Takarazuka Revue at the Imperial

Theater. The video's back cover states "the clichés come thick and fast in this

story of Japan's underground in post WWII." Despite this drawback, a few implausible

actions by certain characters, and some stiff dialogue in places, the film does

have a fairly fast-paced plot and a surprise ending.

An American agent named Jim Carter comes to Japan to try to find his former

college classmate, Taro Matsudo, who has become mixed up in Communist agitation.

Taro's father, a high-level Japanese government official, explains to Jim that

his son became very confused when his kamikaze pilot training was cut short by

the announcement of the war's end. Jim gets assistance from Steffi Novak, whose

sister is being held prisoner by the North Koreans, and he also enlists the help

of Namiko, a dancer in the Takarazuka Revue who has loved Taro for many years

despite his shady behavior after the war's end. In the end, Taro commits a

quick-thinking act of suicide that saves Jim, Steffi, and his father and brings

down the the local Communist group boss named Mr. Oyama.

A laughably unrealistic four-minute flashback scene portrays Taro's education

to become a kamikaze pilot. The 25 or so students in the kamikaze class watch US

Navy films of kamikaze attacks that were not even released until after the end

of WWII. Taro's father describes his son's kamikaze training, although it is

unclear how he found out since they have been estranged ever since the war's end

(22:15 - 26:15):

That shows how he has changed, but I can understand it for I watched the

change take place, not only toward you but toward me and everything else

that was once important to him. You see, Taro was trained to be a kamikaze

pilot. Day after day, hour after hour, he sat in a classroom studying just

one subject, how to die—not how to die in the manner expected of a soldier,

but how to commit suicide.

In planes loaded with high explosives, they were trained to hurl

themselves into battle with only one thought in mind: to reach their

objective. That their own lives would be forfeited wasn't important since

they were taught that self-destruction was the only real glory. It was a

fantastic training but deadly thorough. Nothing was overlooked which would

play on their emotion and obtain the desired result.

The movie's flight students appear to have completed their training to be

kamikaze pilots without ever stepping out of the classroom. The young men at the

kamikaze school look like robots who have been brainwashed. Taro fearfully

watches the film clips of kamikaze aircraft crashing into ships, but then he and

the other students jump up and yell like children in a delayed reaction after an

aircraft carrier erupts in flames and smoke due to a kamikaze crash. Taro's

father continues his description of the far-fetched school:

When an ordinary student graduates, he is given a diploma. When a

kamikaze student graduates, he is given funeral rites, which enshrine him as

a Japanese god. Fingernail clippings and locks of hair were placed in the

envelopes as symbolic remains of the living dead, and they drank a portion

of sacred wine to give them immortality. After that, they were ready for

their first mission and their last. But Taro found it unnecessary to

complete the rites. Japan had surrendered.

At the announcement of surrender, Taro throws his wine glass and breaks it on

the table (real kamikaze pilots would have drunk sake or water from small

sake

cups rather than wine glasses), and he leaves the classroom in a daze. His

father explains to Jim that Taro never came home after that day and that he had

no idea where he was until he had seen his picture one day in the newspaper.

The actions of the characters of both Taro and Namiko have unclear motives. The film never mentions why Taro ended up in the kamikaze training

school, since it seems like he would have mixed feelings if he had attended an

American university. He seems to be much too old to be training as a pilot,

since Japanese WWII pilots usually were in their late teens or early

twenties, but the actor who plays Taro was 40 years old. The movie never

explains why Taro remained depressed and in confusion for over five years after the

end of the war and then somehow got involved with Communist activities.

Namiko portrays a sweet innocent woman who loves Taro, but it seems quite

strange that she has kept so committed to him for many years even though he has

not reciprocated in any way since his days in training as a kamikaze pilot. The

following speech by Namiko to Taro sounds more like propaganda for the

accomplishments of American occupation forces than the words from a woman in

love:

Please, Taro, you think we are blind, but it is you who cannot see. In

the old Japan, did the farmer ever own his land? Could the worker demand

fair treatment? Was the voice of the lowest as strong as that of the

highest? Those things are good, Taro. Why would you destroy them?

Tokyo File 212's many scenes in Japan under American occupation make it

interesting from just an historical perspective, but this B movie has enough

plot and humorous moments (some unintentional like the kamikaze pilot school) to

make it an enjoyable watch.

Graduation ceremony at kamikaze pilot school

|