Oil, Fire, and Fate: The Sinking of

the USS Mississinewa (AO-59) in WWII by Japan's Secret Weapon

by Michael Mair

SMJ Publishing, 2008, 642 pages

This WWII ship history stands in a class by itself. Michael Mair, son of a

USS Mississinewa (AO-59) crewman, performed an overwhelming amount of

research to write this book. He spent ten years conducting extensive interviews with

survivors of this auxiliary oiler that sank when hit by a kaiten weapon at

Ulithi Atoll on November 20, 1944. In addition, Mair contacted others associated

with the Japanese kaiten attack and Mississinewa's sinking, including

members of the Kaiten Association in Japan and veterans of ships at Ulithi Atoll

who assisted in the rescue of Mississinewa crewmen.

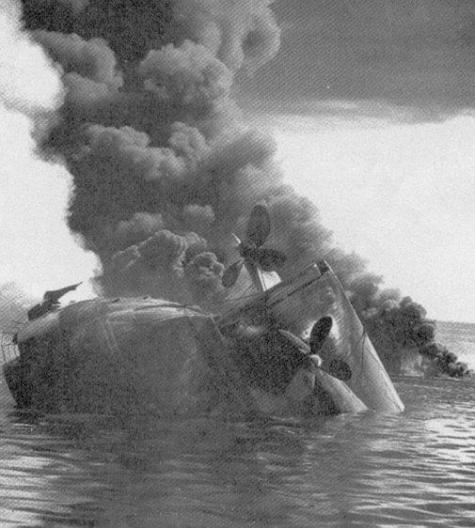

Two Japanese I-class submarines carrying four kaiten apiece participated in

the attack on the American anchorage at Ulithi. Before sunrise on November 20,

1944, I-47 successfully launched all four kaiten while I-36 got

off only one with the other three jammed in their racks on top of the submarine.

The kaiten piloted by Sekio Nishina, co-creator of the kaiten human-guided

torpedo, hit Mississinewa at about 0545. The oiler loaded with fuel exploded,

flames started spreading rapidly, and crewmen quickly recognized that the fire

could not be controlled. Nearby ships sent out small boats that rescued many men

who escaped the flaming waters around Mississinewa, but 63 crewmen lost

their lives in the kaiten attack.

After two short opening chapters, the first summarizing the kaiten attack on

Mississinewa and the second about the buildup of the US oiler tanker

fleet, most of the book's 14 chapters in general chronological order follow a similar pattern. In each chapter

the author describes experiences of various individual Mississinewa

crewmen or other persons connected with Mississinewa. Unforgettable

chapters include the one where crewmembers describe what happened right after

the kaiten exploded and the final one where survivors return home. A few chapters have a

different format. Chapters 8 and 9 provide background on kaiten weapons and on

the Kikusui mission in which kaiten attacked Ulithi. Chapter 13 analyzes what

happened to each of the five kaiten weapons launched by submarines I-36 and

I-47.

Due to the huge number of eyewitness accounts in this lengthy

history, a complete index at the end of the book greatly aids anyone who wants to find stories about

specific individuals. Forty pages of End Notes include the names of countless

veterans interviewed by Mair. The book also has many wartime photos,

including several of the flaming and smoking Mississinewa. The extended

Epilogue, consisting of two parts written by Chip Lambert, tells about the

discovery of the sunken Mississinewa in April 2001 and the actions taken to deal

with oil leaking from the ship.

Account after account of the aftermath of the kaiten's hit on Mississinewa

refer to certain aspects of the disaster. Many survivors talk about droplets of hot

oil raining down on them. Also, quite a few personal stories mention

non-swimmers, many who stood frozen in fear at the ship's rail not able to jump

overboard. Several mention a Kingfisher floatplane that saved several crewmen. The pilot, Blase

Zamucen, received a Navy and Marine Corps Medal with a citation that included

the following words: "He taxied his plane to within twenty feet of the blazing

oil in spite of the intense heat, smoke, and exploding ammunition and threw a

buoyed line to the men struggling in the oil near the flames. Upon towing one

group clear of the increasing ring of flames he again approached close to the

flames and towed a second group to safety."

Japanese sources, including the Kaiten Association Chairman and the former

navigator of the submarine I-53, provided much information for the

chapters on kaiten and the Kikusui mission. These sources also assisted in

understanding what happened to the five kaiten launched at Ulithi Atoll. The

background chapter on kaiten uses several extended quotes from Yutaka Yokota's

wartime memoir, The Kaiten Weapon (1962), to describe kaiten training and battle

operations. The two kaiten chapters also have several wartime photos, including

the four-man kaiten crews aboard I-36 and I-47.

Chapter 13, "The US Navy Strikes Back," objectively and thoroughly analyzes

both American and Japanese evidence related to what happened to the five kaiten

launched at Ulithi Lagoon. Mair avoids jumping to conclusions but rather

recognizes in several cases that the fate of each kaiten and its pilot cannot be

determined with complete certainty. In addition to the kaiten piloted by Nishina

that sank Mississinewa, this chapter summarizes the fates of the other four

kaiten (pp. 476-80):

- One rammed and sunk by USS Case (DD-370) at 0538

- One depth charged by USS Rall (DE-304) in Urushi Anchorage at

0653

- One detonated on reef and recovered by US Navy 1/2 mile (0418) or two

miles south of Pugelug Island (1132)

- One detonated on reef south of Pugelug Island and sank back into sea OR

was depth charged and sunk by USS Rall (DE-304) in northeastern

Urushi Anchorage

In contrast to the conclusions above, after I-36 and I-47 returned to Kure

Naval Base, the Japanese Navy exaggerated the battle results of the Kikusui

mission by estimating that three aircraft carriers and two battleships had been

sunk.

The huge number of details included in this ship history makes this book very

difficult to read from cover to cover. On the other hand, some persons, such as

someone associated with Mississinewa, may view these details as the

book's strength. Although many personal stories are quite fascinating, the many

names make it nearly impossible to remember individual crewmembers from one

chapter to another. However, some descriptions of events provide fascinating

details, such as King Neptune's Court where Shellbacks who previously had crossed the

equator take revenge on the Pollywogs who had never been across the equator. In a

humorous event, two Pollywogs try to hide in the potato locker to escape the

wrath of the Shellbacks, but their hiding place gets discovered, and they

receive additional "punishment" when brought before King Neptune's Court. On the

serious side, the collection of personal stories about escapes from the burning ship provide a vivid picture of the panic, horror, and tragedy faced by

Mississinewa crewmen.

Although the book has many wartime photos, it lacks maps and diagrams. The

many place names mentioned make it difficult without maps to visualize the movements of

Mississinewa. Page 477 finally shows a detailed map of the

Ulithi Atoll, but Mississinewa had arrived there more than 200 pages

earlier. One page earlier in the book has a picture of a Navy intelligence map

of Ulithi, but the names of the individual islands are so small that they can

barely be read. The book does not have a diagram of the layout of an auxiliary

oiler, which would be helpful to understand how crewmembers escaped from the

ship after being hit by the kaiten.

The depth and breadth of research included in Oil, Fire, and Fate make this

ship history one of the best written so many years after the end of WWII. The

numerous personal stories based on interviews by the author convey the spirit

shared by Mississinewa's crew and the tragedy that took place so quickly

when the Japanese kaiten rammed into the ship.

Mississinewa's twin screws visible before going under water

|