The Wonderful World of John Duffy: An Autobiography

by John Duffy

Privately published, 1992, 185 pages

John Duffy joined the Navy in December 1940 for six years. He served aboard

the heavy cruiser Louisville (CA-28) for over four years from February 1941 to

April 1945 as a gun turret trainer. The first third of Duffy's autobiography

deals with his wartime experiences aboard Louisville including two hits by

kamikaze aircraft on consecutive days in January 1945. The last chapter returns

to the kamikaze attacks when Japanese media interviewed him in 1995 about a

piece of the kamikaze plane's wing that he recovered from the second hit. The

chapters in between contain some fascinating stories from his work as a civilian

tugboat captain in and around New York Harbor, creator and seller of Duffy

Player Pianos, captain of sightseeing yacht that took trips around New York

City, and pilot of barges and cargo ships.

One day in November 1944, Duffy experienced the first kamikaze attack on the

heavy cruiser Louisville. He had a close call when a Japanese plane missed

hitting the ship's bridge and crashed into the sea alongside where he had been

walking. The blast threw him into the side of gun turret 1 that he had just

left, and one of his shipmates momentarily thought he had disappeared. It turned

out that he did not get hurt and only got wet on his backside, but he never

forgot that close call.

On January 5, 1945, a kamikaze aircraft crashed into gun turret 2 as

Louisville was in route to Lingayen Gulf on Luzon Island in the Philippines to

support the planned invasion there. One crewman was killed, and 52 others were

wounded [1] including Captain Hicks who was badly burned. During the following

morning, Louisville led the way into Lingayen Gulf and fired on shore targets

with her two remaining gun turrets and in the afternoon returned for more shore

bombardment. Late in the afternoon six kamikaze planes attacked Louisville.

Although most were shot down, the fourth one made it through the antiaircraft

fire and crashed into the starboard side at the communications deck. The attack

killed 32 men and wounded 125 others [2], and the severity of the damage forced

Louisville to retire to Mare Island Navy Yard for repairs. Duffy left Louisville

in April 1945, but the ship returned to fight the Japanese again during the

Battle of Okinawa. On June 5,

1945, Louisville got hit a third time by a kamikaze aircraft, which killed 8

men and wounded 37 others [3].

John Duffy received an individual commendation from Louisville's Commanding

Officer for the action taken during the kamikaze attack of January 6, 1945, in

which he "displayed outstanding diligence, skill, bravery, and intelligence in

combating fires and rendering aid to the wounded." He was in charge of 60 1st

Division men, and the following three paragraphs describe his actions in his own

words (pp. 49-50):

All of a sudden, the ship shuddered and I knew we were hit again. I was in

charge of the 1st Division men and I yelled. "We're hit, let's go men!" I was

the first man out the Turret door followed by Lt. Commander Foster and Lt.

Hastin, our Division Officer, then a dozen more men. The starboard side of the

ship was on fire from the focsle deck down. One almost naked body was laying

about ten feet from the turret with the top of his head missing. It was the

Kamikaze pilot that had hit us. He made a direct hit on the Communications

deck.

As the men poured out of the turret behind me they just stood there in shock.

Explosions were still coming from the ammunition lockers at the scene of the

crash. We could see fire there too. Injured men were screaming for help on the

Communications Deck above us. I ordered two men to put out the fire on the

starboard side by leaning over the side with a hose. That fire was coming from a

ruptured aviation fuel pipe that runs the full length of the forecastle on the

outside of the ship's hull. That fuel pipe was probably hit by machine gun

bullets from the Kamikaze just before he slammed into us.

Although there was no easy access to the deck above us, I ordered several men

to scale up the side of the bulkhead (wall) and aid the badly burned victims who

were standing there like zombies. I also ordered three men to crawl under the

rear of Turret 1's overhang, open the hatch there, and get the additional fire

hose from Officers Quarters. These three orders were given only seconds apart

and everyone responded immediately, but when they got near the dead Jap's body,

which was lying right in the way, it slowed them down. I yelled, "Carl Neff,

grab his legs." As I leaned over the body, I noticed that all he had on was the

wrap-around white cloth in his groin area. I then grabbed him under the arms and

lifted. When I did this, his head rolled back and his brain fell out in one

piece onto the deck as though it had never been part of his body. I told Carl,

"Right over the side with him." Then I immediately went back and scooped up his

brain in both hands and threw it over the side. To the men who had no

assignment, I shouted, "Get scrubbers and clean up this mess."

Duffy brought home a piece of the wing from the kamikaze plane that hit

Louisville. The piece had Japanese characters on it that indicated the

plane was a Suisei dive bomber (Allied code name of Judy). Fifty years later, a

reporter from the Yomiuri America newspaper visited his home to interview him

about the kamikaze attack and the piece from the wing. The story about Duffy

appeared in the newspaper on August 18, 1995, with a photograph of his holding the

piece of the kamikaze plane's wing (see photo below).

John Duffy in 1995 with piece of

Suisei dive bomber that crashed

into USS Louisville on January 6, 1945

In the ten days following the publication of the article about John Duffy in

the Yomiuri America, a team from Nippon TV News International Corporation

interviewed him twice in his home. Based on these interviews, in December 1995 a

7-minute segment about Duffy was broadcast in Japan. The book's last chapter

includes a transcript of the second interview. The following two questions and

answers from that interview provide some insight into Duffy's feelings about the

kamikaze attacks (pp. 179, 180, 183).

QUESTION: Mr. Duffy, where was your ship, the USS LOUISVILLE, when the

Japanese kamikaze hit on January 6, 1945?

ANSWER: We were in Lingayen Gulf, Philippine Island Luzon, and after

bombarding shore installations, the ship turned and headed out of the Gulf. So,

we were in the Gulf when we were hit that day.

In speaking about the kamikaze pilot you are looking for I must tell you

this: The crew of the LOUISVILLE was very experienced. We had been through 3

years of war. We had been part of the invasions of most of the islands before we

came to Japanese held Philippines. We had earned 12 bronze battle stars before

your kamikaze came in and made that direct hit which caused us to retire. All

the men on the LOUISVILLE were heroes for my country, just as your pilot was a

hero for Japan. Your kamikaze pilot only gets one shot, whereas, we had shot

down many planes and had seen many splash around the ship.

QUESTION: Many of our pilots were as young as you were at that time. They loved

their country and believed in victory, so they attacked. How do you feel about

that?

ANSWER: Well, they were brave men to do what they did. Some were successful,

some were not. But they kept coming, and we kept coming.

In January 1996, Duffy received a video tape copy of the 7-minute segment

shown during a Japanese news broadcast. He describes his feelings about the

suggestion to have

contact with the dead kamikaze pilot's sister (pp. 184-5):

Included [in the video] were scenes at my home, and of the suicide plane hitting my ship,

where the plane (a JUDY) came from, and information about the Kamikaze Pilot.

Finally, they showed a visit to the dead pilot's Aunt, and to his younger

sister.

It was not easy for me to hide my true feelings, but 50 years have passed

since that bad day in my life. When Nippon TV asked if the dead pilot's sister

could write to me, I said, "I prefer she did not write to me. I pray and I weep,

for my shipmates who lost their lives serving their country."

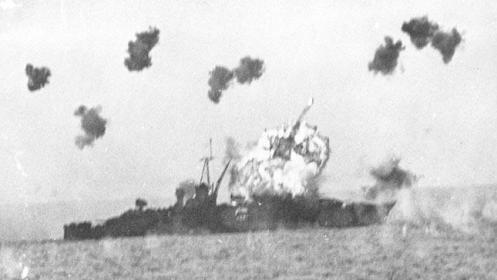

USS Louisville (CA-28) hit by kamikaze plane

in Lingayen Gulf, Philippine Islands, on January 6, 1945

(photographed from USS Salamaua (CVE-96))

At the very end of the book Duffy includes a letter to the President of the

Louisville Reunion in which he describes the request that he received to give

back the piece of the wing to the relatives of the pilot who flew the plane:

Aug 30, 1996

Dear Glen Garnhart,

Yesterday I received a phone call from Japanese importer Mr. K. Tatsuno in

Fort Lee, NJ. He is the man who used to train Kamikaze pilots in my continuing

story.

The last time I spoke to him in his office was in January of 1996. I had

asked him if he would translate my Japanese Kamikaze tape into English. I gave

him a Japanese copy to work with and a blank cassette tape. He said he was busy

but I left him the tapes anyway.

Now here he is 8 months later, with a translation for me and also a letter

from the dead kamikaze's sister from Japan. He said he could translate that

letter too.

I had previously told Nippon TV I did not want any contact with his sister.

It is my belief that Tokyo has contacted Mr. Tatsuno to ask if they could have

the piece of wreckage of the plane for the pilot's relatives.

When the request was made, I said, "NO." Mr. Tatsuno asked, "Why?"

I said, "That piece of wreckage reminds me of my dead comrades."

He said something like, "The war is over, return this piece so this man can

go to heaven."

I said, "No, never."

He then started to preach about all the war related items that have been

returned to Japan. I stopped him when he started to talk about the atomic bombs

being dropped on Japan.

I said, "Let's not argue, you ain't getting it, and that's final."

Some of you gunners will be at the Portland reunion and it was you men that

put the holes in this plane. The Japanese say, "It is painful to see the many

bullet holes." And you men should be proud to say you left your mark on purpose.

I have had bad dreams over the years. I picture my 32 dead comrades locked in

a room and they are very angry. They hate what the kamikaze did to them.

I turn to you my shipmates, "Should I return this piece of wreckage, or may I

keep it. I'll abide by your decision- - - - - -maybe."

God bless you all, and the ones you love.

Your Shipmate,

John Duffy

UPDATE: At the USS LOUISVILLE reunion which was held Sept 2, 1996 until Sept

8, 1996, all hands present were polled and were very vocal in their decision

that I should NOT give the piece of wreckage I have, back to the Japanese.

CASE

CLOSED.

These excerpts illustrate John Duffy's strong emotions five

decades after the kamikaze plane crashed into his ship in Lingayen Gulf.

Although the book's copyright year is 1992, the last chapter on visits to

Duffy's home by the Japanese media in 1995 obviously were written later, so most

likely this privately published book had a second printing with the added

chapter. The front of the book has a slip of paper entitled "UPDATE: November

1997," which explains that a Ms. Hino from Japan also contacted Duffy when

writing a book. She asked him questions about kamikaze, but he just told her

"she would find all my answers in my book." He received a copy of her 1997

children's book Tsubasa no kakera: Tokkou ni chitta kaigun yobi gakusei no

seishun (Wing fragment: Youth of Navy reserve students who died in special

attacks). The book covers the lives of several Japanese Navy pilots, and its

title comes from the wing piece in John Duffy's possession. The book includes

photographs of the heavy cruiser Louisville and Duffy's holding the

kamikaze plane wing fragment. Hino explains in the book that the Suisei

dive bomber piloted by Tadasu Fukino from Mabalacat Air Base hit Louisville

on January 6, 1945.

Notes

1. Page 48 gives these numbers. Rielly (2010, 319)

states 59 men were wounded. 2. Page 50 gives

these numbers. Rielly (2010, 161, 319) states the kamikaze attack killed 36 and

wounded 56 on January 6, 1945. 3. Rielly 2010, 289,

324. Sources Cited

Hino, Takako. 1997.

Tsubasa no kakera: Tokkō ni chitta

kaigun yobi gakusei no seishun (Wing fragment: Youth of Navy reserve

students who died in special attacks). Tōkyō: Kōdansha.

Rielly, Robin L. 2010. Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A

Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships, by Aircraft

and Other Means. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

|