Kaiten: Japan's Secret Manned Suicide Submarine and the First American Ship It Sank in WWII

by Michael Mair and Joy Waldron

Berkley Caliber, 2014, 363 pages

Michael Mair's father John served aboard the auxiliary oiler

Mississinewa (AO-59) for six months from the ship's commissioning to her

sinking by a kaiten manned suicide torpedo on November 20, 1944. John survived

his ship's sinking by jumping 20 feet from the burning deck to a clearing in the water

blazing with burning oil and by swimming to the nearest rescue boat sent from another ship.

For many years his son Michael thoroughly researched Mississinewa's

story, mainly through interviews of surviving crewmen but also by examination of

written sources such as U.S. Navy Action Reports. About half of the chapters in

this book tell the history of the oiler Mississinewa, and the other

chapters provide background on the kaiten human torpedo program along with

details about the kaiten pilot who sank Mississinewa while anchored in

Ulithi Lagoon.

When the 3,418 pounds of explosives loaded into the front part of the kaiten

manned torpedo exploded after hitting Mississinewa's starboard side at

0545 on November 20, 1944, the oiler became engulfed in flames and burned out of

control. The water with flaming oil around much the ship made escape difficult

for those who remained alive after the initial explosion. The 5-inch/38 caliber

gun magazine blew up at 0605, and Mississinewa disappeared beneath the

surface of Ulithi Lagoon at 0905. The kaiten attack killed 63 men and wounded

many more out of total crew of 278 men.

The book's most memorable parts give numerous harrowing eyewitness accounts

by Mississinewa survivors and the other ship crewmen who rescued

survivors or who witnessed the initial explosion and frightening aftermath. They

describe the confusion and terror after the kaiten's explosion, desperate

attempts to get off the blazing ship, frightening experiences in the oily water

with flames on top, daring rescues by boats sent from nearby ships, and

crewmen's feelings after being rescued until they finally reached the California coast and

their homes. A few personal stories surprisingly mention men who could not

swim, which obviously led to their panic with the ship ablaze and sinking into

the water. The story below, put together based on interviews with the crewman

involved, the Mississinewa captain, and a crewman from another oiler

anchored nearby, provides one example of the many accounts included in the book

(pp. 185-6):

Only one man on the ship's bow survived. At 0545 that morning Eugene

Cooley had awakened the moment his skivvies caught fire and scorched his

skin. He heard a dog's frantic barking coming from under the starboard

3-inch/50 mount and saw the ship's mascot, Salvo. A wave of flame swept over

the starboard mount, causing Cooley to forget about saving the dog and find

an escape route. The roar of flames behind him convinced the New York boy to

abandon ship. Without hesitation, he dived headfirst from the bow into the

flaming water. The cool salt water took away some of his fear, allowing him

to remember basic water skills. He splashed the flames away, gulped for air,

and dived deep, splashing again each time as he rose to the surface for a

breath. At last he cleared the flames several yards from the bow, surfacing

for the last time amid oil and roiling smoke. Cooley flipped over on his

back, choking as his lungs ingested smoke, and nearly blind from oil that

burned his eyes. Mississinewa had disappeared behind a black curtain.

He distanced himself from the flare-ups caused by fresh AV gas feeding the

fire and heard a voice through the din; a small boat from Mascoma

suddenly appeared, and two pairs of hands hauled the exhausted boy aboard.

Mississinewa rolls to port, slipping from sight

Several survivors mention the Kingfisher floatplane that came in close to the

flaming oil and saved them. Three months after Mississinewa's sinking, the

Kingfisher pilot, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Blase Zamucen, and his radioman

Russell Evinrude received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal from the Commander of

the First Carrier Task Force, Pacific, in the name of the President of the

United States. Zamucen's citation reads (p. 225):

For distinguishing himself by heroism in the rescue of survivors of the

burning, torpedoed ship. While piloting a cruiser based airplane, he saw the

ship torpedoed. He instantly turned his plane and flew low over the then

blazing ship and seeing survivors struggling in the burning oil near the

ship, with no boats in the vicinity, immediately landed his plane to affect

rescue. He taxied the plane to within 20 feet of the blazing oil in spite of

the intense heat, smoke, and exploding ammunition and threw a buoyed line to

the men struggling in the oil near the flames. Upon towing one group clear

of the increasing ring of flames he again approached close to the flames and

towed a second group to safety. After the second trip, boats approached the

fire and he resumed his station on antisubmarine patrol. His utter disregard

of his own safety was at all times in keeping with the highest traditions of

the United States Navy.

M. A. Mitscher,

Vice Admiral, U.S. Navy

Earlier chapters cover the creation, development, and testing of the kaiten

weapon by Hiroshi Kuroki and Sekio Nishina. The weapon was based on the Type 93 torpedo, nicknamed the Long Lance. Kuroki and another kaiten crewman died in a training accident

when their kaiten torpedo got stuck in the bottom of Tokuyama Bay on September

6, 1944. Nishina carried Kuroki's ashes with him from Ōtsushima Kaiten Base when he led the Kikusui Unit to

make special (suicide) attacks against American ships. Two Japanese I-class

submarines carried four kaiten apiece to attack American ships at the Ulithi

anchorage. Before sunrise on November 20, 1944, submarine I-47 successfully

launched all four kaiten, but submarine I-36 got off only one while the

other three jammed in their racks on top of the submarine. The kaiten piloted by

Nishina hit Mississinewa, but the other four kaiten did not hit any

ships. During the war a total of 106 kaiten pilots lost their lives including 15

men killed in training accidents.

The main sources used by the authors to describe the Japanese kaiten program

were published English translations (Kaiten Weapon (1962)

by former kaiten pilot Yutaka Yokota and I-Boat Captain (1976) by former

I-47 submarine commander who carried Nishina and three other kaiten

pilots to Ulithi) and information provided by Japanese contacts familiar with

kaiten operations such a former kaiten pilot Toshiharu Konada, who was

Chairman of the Kaiten Association for many years. The book has a ten-page

Bibliography that demonstrates the thoroughness of research for the book.

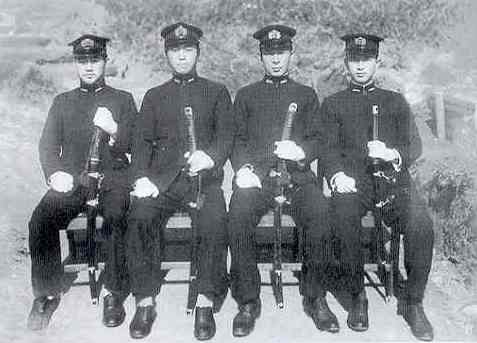

(Left to right) Kaiten pilots Ens. Akira Sato, Sub. Lt. Sekio

Nishina, Sub. Lt. Hitoshi Fukuda, and Ens. Kozo Watanabe

were carried to their Ulithi launch point by submarine I-47

After an exciting Prologue that

introduces the kaiten attack at Ulithi, the first three chapters get the book

off to a slow start with general information about attack submersibles, the

Pearl Harbor attack, and the Battle of Midway, which seem to have little

direct relevance to the book's main theme. The book's subtitle refers to the kaiten as

a submarine, but it is more appropriately termed a torpedo. The kaiten manned torpedo

was launched from a mother submarine, but it was not an actual submarine with the

ability to maneuver independently underwater over a wide range. The confusion

starts in the Prologue when Nishina's kaiten is described as "a tiny manned

submersible carrying a torpedo just launched from its mother submarine" (p. 3).

In reality, the kaiten is a torpedo itself and does not carry a separate

torpedo. A little later the kaiten weapons are referred to as "special attack

submarines" (p. 11) even though this phrase more properly refers to the Japanese

midget submarines that carried out tokkō (special attack)

operations throughout the war. The authors confusingly refer to kaiten attack on

Mississinewa as the "first suicide attack by a Japanese submarine pilot"

(p. 18), but this more appropriately refers to nine midget submarine pilots who

lost their lives during the Pearl Harbor attack, since they expected to lose

their lives during their attack mission that had been designated as tokkō

(special attack).

Many WWII ship histories get told by a former crewman, but this book has

snippets from numerous Mississinewa crewmen with no central character.

The Japanese side of the attack is presented in much the same way with

quotations from many different sources, but in some places the authors make

assumptions about the kaiten pilots' thoughts and feelings that are not warranted such as an overemphasis on their dedication to the Japanese emperor.

For example, the final thoughts of kaiten pilot Sekio Nishina, who died in the

attack on Mississinewa and who did not radio back any messages during his

attack run, are presented as follows (p. 3): "He thought of his life and he

thought of his death. He thought of the men who would follow after him, inspired

by his success, and the family he had left behind in his island nation. Most of

all he thought of the emperor and the sacred mission to save his country. All

these fragmented images flashed through his mind in seconds, then he was

consumed by the task of holding his craft on course." Of course, nobody

really knows

what Nishina thought during the last minutes of his life as his kaiten entered

the lagoon at Ulithi and headed toward Mississinewa.

The middle of the book contains 16 pages of historical photographs including

kaiten weapons and pilots and the oiler Mississinewa and crewmen. A detailed map of Ulithi Atoll

shows locations of

key U.S. ships when the kaiten attacked, and another map indicates the five kaiten torpedoes' most likely

routes and final points where they were destroyed based on available evidence. Michael

Mair researched for many years and collaborated with Minoru Yamada, navigator of

submarine I-53, in order to determine where the two submarines launched the five

kaiten and what happened to the kaiten after they left the mother submarines.

The known evidence is clearly presented to arrive at what most likely happened,

but in the end the fate of each of the five kaiten cannot be determined with complete

certainty. One appendix tells the story of underwater dives that resulted in the

eventual finding of the sunken oiler in 2001, and another appendix tells about

the dive in 2013 by Mair to explore the underwater remains of Mississinewa.

|