In the Wake of Jellybean

by Ray Novotny

Self Published, 2005, 354 pages

Seven Japanese kamikaze aircraft attacked the American destroyer USS Hyman

(DD-732) on April 6, 1945, the date of the largest mass kamikaze attack of World

War II. The ship's gunners, sometimes with assistance from other ships, shot

down all of the attacking planes except one. The fourth plane, a Zero fighter,

managed to crash into the ship between the stacks even though heavily damaged by

gunfire. Former Hyman crewman Oscar Murray described the Zero that hit the

ship (p. 240):

My General Quarters station was as a gunner on a 20-mm anti-aircraft gun. I

wonder if things would have been different had I been able to fire another two

seconds at the Japanese plane that struck and nearly sank us. He was so close.

The head of the pilot turned toward us as he struck the stacks. Just before

striking the ship, I, or others, shot off his left wing but the plane's momentum

carried him into the ship. The plane's explosion, along with its gasoline, blew

away the area between the two stacks almost to the waterline, and with most of

the forward torpedo mount. Flaming gasoline flowed in all the surrounding areas,

burning or killing many below and several above deck.

As I followed the plane, my gun came to a complete stop, abruptly halted by the

gun stops designed to prevent guns from rotating too far and doing damage to the

ship's superstructure. By then he was out of sight and immediately struck the

ship. Normally, Japanese planes exploded upon a direct hit but this one didn't.

Had I or others been able to hit him with more rounds, perhaps he would have

done so, I will never know: I know we did our best.

At Hyman's decommissioning ceremony in 1969, Captain Horgaard described the explosion after the plane crash (p. 352), "A very

heavy and devastating explosion took place at the scene 1 minute and 42 seconds

later, probably from bombs carried by the plane." However, some in the crew had

a different theory on the explosion (pp.217-8):

The Director crew carefully watched the fourth Kamikaze before it crashed into

the ship. They reported the plane did not appear to carry an external bomb,

however, an extra fuel tank was visible. One wing was shot off by 20-mm and

40-mm automatic guns at about 800 yards, setting the plane on fire. It then

veered aft toward the midship section and struck both smokestacks, smashed into

the forward torpedo tube mount and tore off the starboard tube barrel with its

torpedo; the other four torpedoes were never found.

Even Captain Horgaard had a similar opinion about the delayed explosion in

his action report prepared soon after the kamikaze attack (p. 261), "Resulting

fire around forward torpedoes apparently exploded one warhead causing extensive

damage."

The crash by the kamikaze plane and the subsequent explosion killed 12 and

wounded 41 men aboard Hyman. On the same day, the nearby

destroyer Howorth

(DD-592) also got attacked by multiple kamikaze aircraft, and one hit the ship

causing 9 deaths and 14 wounded.

Author Ray Novotny served as an Electrician Second Class in Interior

Communications aboard Hyman from her commissioning in June 1944 to early 1946

when she returned to the States. This privately-published history published

sixty years after the end of WWII contains many stories, which give the book its charm. The book generally follows

the chronological history of the destroyer Hyman with interesting digressions

and personal observations. The book's center section has 22 pages of

photographs. The title comes from Hyman's code name of Jelly Bean as the

flagship for ships that were firing on Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo

Jima.

The book's information on Japan's kamikaze operations contains quite a few

errors. Novotny asserts that a few Japanese pilots "chose to land safely in the

sea and risk the possibility of capture over the certainty of death" (p.263),

but no documented case exists where a kamikaze pilot voluntarily chose to land

safely in the sea rather than complete his mission, although a few

pilots did have to make forced landings in the sea when their planes developed

engine problems or had been hit by enemy fire, and the men managed to survive to

the end of the war. On March 18, 1945, the carrier Franklin did not get hit and

severely damaged by kamikaze aircraft as stated in the book (p. 200) but rather

got hit by two bombs dropped from a dive bomber on March 19. Japanese names

frequently get misspelled (e.g., Mushai instead of Musashi, Kamikazi instead of

Kamikaze, Shinyu instead of Shin'yō when referring to suicide torpedo boats). The

Japanese pilots who participated in kamikaze attacks during the Battle of

Okinawa are referred to inaccurately as Kikusuis or Floating Chrysanthemum (p.

212), but Kikusui was rather the name used by the Japanese to refer to the ten

mass kamikaze attacks rather than the pilots themselves.

The book's last chapters describe how Hyman's men handled the surrender of Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) and Kosrae (formerly Kusaie), two small islands now

part of the Federated States of Micronesia. The crew spent three months on these

tropical islands and became friends with the natives who lived in this paradise. The

government of Pohnpei invited Hyman veterans and their spouses to the 50th

anniversary of their liberation from the Japanese. The author and nine other

Hyman crewmen returned to Pohnpei in September 1995 to celebrate Liberation Day,

when they were recognized and honored by the natives for their key role in the

island's history. The book's center section has four pages of historical

photographs related to the liberation of Pohnpei and Kosrae and five pages of

photographs of the 1995 return to Pohnpei by ten Hyman veterans.

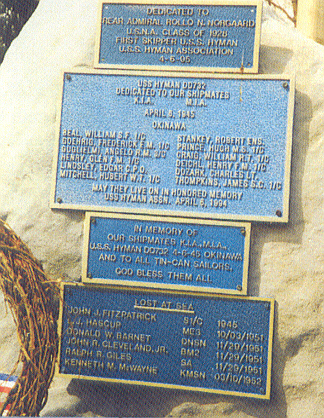

Hyman Memorial Stone and Plaques

April 6. 1995, New Castle, IN

In the Wake of Jellybean contains many vignettes of what actually happened

during the war with no attempt to glorify the crewmen's actions. One story tells

about the harsh punishment meted out by the captain when a crewman hit an

officer with his fist when given an order to go topside and perform a routine

task. Another gives the author's reactions to a suicide committed by a Hyman

crewman during the Battle of Iwo Jima, when the destroyer played a key role with

her spotlight and guns in support of the Marines' climb up Mount Suribachi. The

story is given below in its entirety due to the difficulty in obtaining this

self-published book (pp. 172-5):

0600 HOURS. The HYMAN was steaming north, close to the base of Suribachi.

Another destroyer was following behind in HYMAN's wake, less than a mile away.

An intercom call came to the I.C. Room from the stern lookout reporting a

problem with his sound-powered headset. After providing him with a replacement

set, we engaged in some banter for a few minutes.

Over the lookout's shoulder, my attention was caught by a small, round object

floating past, a few feet off the port stern. It appeared to be a human head. A

hard look confirmed it was one of the crewmen. I blurted out to the lookout,

even though he stood only a few inches away, "Man overboard!"He wheeled in the

direction I was looking and immediately called the bridge on his headset. The

ship continued moving; there appeared to be no acknowledgment of the urgent

message. "Call again!" I shouted once more. "The bridge got the first message.

They said the ship trailing us would pick him up."

Several of the crew joined us to watch the man overboard. Slowly, ever so

slowly, the head drifted further away in the ship's wake. The victim, whoever he

was, made no attempt to swim, shout, or signal distress. It was a head floating

away in the gray, murky water near the base of Suribachi.

When about half-way between the two ships, the overboard crewman, facing the

HYMAN, held up one arm for a few seconds, as if to wave goodbye, then quickly

disappeared beneath the surface. The body was never recovered.

Startled by what we had just witnessed, I proceeded to the port side midship. A

group of off-duty crewmen, some seated on the deck, were casually talking among

themselves. They appeared unconcerned about anything.

"Did anybody see what happened," I asked.

A couple of them answered, as though irritated, "Yeah," one of them replied, "He

jumped overboard."

I asked for details, "How did it happen? Who was it?"

"It was Fitzgerald," one of them finally answered. "He was off watch—a gunners

mate. Without talking to anyone he calmly walked over to the port rail where we

were shooting the breeze. He lifted himself onto the rail, balanced himself

against a whaleboat davit, turned, glanced around, and toppled overboard,

without saying a word."

"Did you know he was going to jump? Did anyone try to stop him?" There was a

long pause. A couple of crewmen were obviously irritated by the inquiries. I

repeated the questions.

"We knew he was going to jump." Another one contemptuously added, "Fuck him. If

he wants to kill himself, let him." The others expressed similar deprecating

remarks, and seemed to share the same attitude.

I was surprised and disappointed by the indifference to the death of a shipmate.

Had the battle conditions we already experienced made these men so callous they

could watch calmly as another crewman took his own life? Why was no attempt made

to stop Fitzgerald? I would have an answer, but not that day.

Later that morning other facts came out. Fitzgerald had exhibited signs of

extreme depression and nervousness since D-DAY, February 19. He was said to be

agitated, openly frightened, and expressed a strong premonition of death. Only

the day before he had fired on one of our own planes and had to be relieved. He

was clearly a victim of "battle fatigue," or "shell-shock" as it was named

during WWI.

It was difficult to comprehend the negative feelings of the men who witnessed

the suicide. They evidenced no remorse over their own unwillingness or failure

to save the victim. Indeed, there appeared to be an air of contempt. The more

the witnesses talked, the more apparent became their lack of concern.

Aboard the HYMAN, there was unexpressed code of conduct: It was important—in

fact, criminal—not to show or express fear in dangerous situations. The

Hispanics have a word for it: Machismo. It was essential for the safety of the

ship and crew that each man behave in a calm, professional manner, and not

exhibit fear. Emotional expressions were acceptable, but showing fear was not.

Self-control was not only expected, it was necessary to safety and discipline.

No one ever explained how to behave under the danger and stress of battle

conditions. It was something that, somehow, was picked up. Was it a result of

strict training, discipline, or camaraderie that made the crew act the "right

way?" Probably all three.

The second day of the Iwo invasion, the ship was off the western shore. A chow

line, waiting for lunch, had formed in the forward passageway. Suddenly, a huge

plume of white water erupted close to the bow. The enemy had our range. But it

was a single shot, no more.

As the water fountain soared, skyward, the conversation stopped for only as long

as it took the water to collapse back into the gray sea. The crewmen exchanged

knowing glances, and then resumed their conversations without missing a beat or

making a comment about the near miss.

My unspoken reaction was: This is a cool bunch of cookies, kids really, but

cool. It was a comfortable feeling being with such an unflappable bunch of guys.

Why hadn't the crewmen who witnessed Fitzgerald's suicide acted to prevent him

from leaping overboard? It was because he exhibited weakness, an unforgivable

condition in battle; the crew had only contempt for this character flaw.

To be weak or undependable in warfare is an invitation to die. If comrades can't

be depended upon, it could result in death. The Navy trains and drills sailors

constantly to be knowledgeable and dependable; there is no other way. The unfit

are usually weeded out early in the training process, but a few sometimes slip

through.

The negative feeling about Fitzpatrick's death was so strong that it wasn't

until 1997 when his name was added to the HYMAN's Memorial Rock in New Castle,

Indiana. Each year, as I look at the list of honored dead, I am reminded of the

sad circumstances of his death. It is not a comfortable feeling to see his name

listed among those crewmembers killed by enemy action. But in a real sense, he

was no less a victim than the other crewmen; he, too, paid the ultimate price by

taking his own life under the most adverse conditions.

USS Hyman Memorial and seven Plank Owners at 60th

Anniversary Memorial Ceremony (April 6, 2005) in New Castle, IN

(L to R) Ray Novotny, Bob Moldenhauer, Paul Hommel,

Leo Carroll, Ed Heffner, Harry Greene, Dick Leitch

Hyman was one of four ships in DesDiv (Destroyer Division) 126. The other

destroyers were Mannert L. Abele (DD-733),

Purdy (DD-734), and Drexler

(DD-741). During the Battle of Okinawa, kamikaze attacks sank both Mannert L.

Abele and Drexler, and Purdy got hit by a kamikaze plane that killed 13 and

wounded 27 men.

Ray Novotny pauses to remember lost shipmates at

60th Anniversary Memorial Ceremony (April 6, 2005)

|