The Big E: The Story of the USS Enterprise

by Edward P. Stafford

Dell, 1962, 512 pages

The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) participated in 20 of 22

major battles during the Pacific War. The exciting history of The Big E

describes the exploits of this aircraft carrier and her air group until she got knocked

out of the war by a kamikaze aircraft attack on May 14, 1945, during the Battle

of Okinawa. Enterprise and her air group downed a total of 911 Japanese

planes and sank 71 ships during the war.

The author Edward P. Stafford, after commanding a subchaser in World War II,

served as destroyer escort Abercrombie's First Lieutenant and later as

Executive Officer until May 1946, just before the ship was decommissioned. He

has authored other books including Far and the Deep: The Submarine from U-Boat to

Polaris (1967), Little Ship, Big War:

The Saga of DE343 (1986), and Subchaser (1988). His World War II

naval experience contributes to The Big E's realistic depictions of

battles and shipboard activities.

This classic ship history has been highly acclaimed since its original

publication in 1962 by Random House in hardback and Dell in paperback.

Ballantine published two separate editions in 1974 and 1980. As evidence of the

book's enduring popularity, the U.S. Naval Institute published new editions of

The Big E in 1988, 2002, and 2016. Although the 1962 Dell paperback

edition used for this book review lacks photos, more recent editions of the book

include photos. The Dell edition does have a map of the western Pacific Ocean to

show locations of significant actions of Enterprise during World War

II.

The Acknowledgments and Biographical Notes sections in back summarize

Stafford's meticulous research, which included examination of Enterprise's Deck Log and

official Action Reports and War Diaries. He also interviewed numerous former

officers, crewmen, and air group members. In addition, he used about 100

questionnaires returned based on a solicitation that was coordinated by the historical

board of the USS Enterprise Association in the years just after World War

II. The depth of the stories included in this history reflect Stafford's

comprehensive research. He focuses on the history of the ship and her air

group, and he does not mention many personal stories

The last chapter entitled "Tomi Zai" has four pages about the Japanese

kamikaze attack that heavily damaged Enterprise. The final moments are

described below (pp. 497-499):

But from the navigating bridge, as the pretty, deadly, brown-green Zeke

with the big bomb under its belly slanted down over the port quarter, it

looked as if he would overshoot and crash to starboard. The enemy pilot must

have thought so too, because halfway up the deck he rolled left through the

forward elevator. In the next split second, while the sounds of torn timbers

and tortured metal were still at crescendo, the bomb roared off five decks

down, and incredulous watchers on nearby ships saw the Big E's Number One

elevator, the cap of a heavy pillar of gray and white smoke, soar 400 feet

into the sky, hang for a second and fall back into the sea.

…

Enterprise was badly hurt. Fire towered redly under the black

smoke that filled the hole where the forward elevator had been. Flames

filled the forward end of the hangar deck and licked at the ammunition

supply for the forward five-inch guns on both sides. The flight deck was

blasted up three feet aft of the demolished elevator. Other fires smoldered

in clothing and bedding in the ruined officers' quarters around the elevator

pit. The gasoline system was wrecked, its pressure main crushed and three of

the four tanks leaking. The forward guns were out of action. There were

twenty-feet holes in her decks down to the third. Watertight integrity

forward was nonexistent. With her buckled deck and gaping elevator hole she

could no longer operate her planes. Worst of all, her holes and her smoke

marked her as a cripple for the other Kamikazes closing the force.

…

Seventeen minutes after she was hit, Enterprise had her fires

under control and in another thirteen minutes they were out. Never, during

that time, did she leave her assigned station in the formation. But she was

down seven feet by the bow and up three by the stern with the 2,000 tons of

water that had entered through the ruptured fire main and had been poured

onto her fires. Pumps of all kinds were rigged, and in thirty-six hours her

trim had been restored to normal.

The Big E, with her competence, had also had luck. The enemy bomb had

exploded in a storeroom full of baled rags, in the vicinity of stored sheets

of heavy steel hull plate, smothering a large part of the shrapnel. The

Number Two elevator had been in use at the time of the hit and the men who

would normally have been in the forward were well aft and out of the way.

Her casualties had been light for such heavy damage, thirteen killed and

sixty-eight wounded. Eight men who were blown overboard were promptly picked

up by the destroyer Waldron, some standing, comfortably drying out,

on a fifteen-foot section of the elevator.

For over 50 years, it was thought mistakenly that Enterprise had been

hit by a Zero fighter pilot named Tomi Zai. This name was determined incorrectly

from information found in a pocket when his body was found (p. 499). Kan Sugahara, a graduate in the 77th class at the Japanese Naval Academy at

Etajima, was instrumental in the determination of the correct identity of the

kamikaze pilot who hit the carrier Enterprise. He examined Japanese records of

Kamikaze Corps Zero fighter-bomber pilots who died on May 14, 1945, and

concluded that (Shunsuke) Tomiyasu had to be the same person named Tomi Zai by the

Americans based on the similarity of the kanji (Chinese characters) in the names

and based on Tomiyasu's sortie time from Kanoya Air Base. See web page on Shunsuke Tomiyasu

for related information.

On April 11, 1945, a Japanese Suisei Dive Bomber (Allied code name of Judy) hit Enterprise. The following paragraph describes the hit

(p. 486):

To the gunners in the two port quarter 40-millimeter mounts it seemed a

personal duel. The Judy was headed directly for them, desperately trying to

crush and burn the gun tubs full of sailors by his own death. They had

learned that their only chance was to take his plane apart with their

bullets before it reached them. They stuck to their weapons, hammering at

the Judy until it filled the world before them, hit and disintegrated in a

roar and blast and sudden silence like the end of the earth. A seaman was

blown overboard and two more fell with broken legs and arms. The Judy's wing

had hit between the two mounts. His engine dished in the hull plating, and

his bomb grazed the ship's side and detonated under the turn in the bilge,

shaking her as a terrier shakes a snake. Two hundred and twenty-five feet

from the explosion, high on the island a few feet forward of the mast, the

structural supports for the big SK air search radar were snapped, and it

ground to a stop. The yardarms whipped so violently that the starboard one

snapped off six feet from the end and fell, dangling by its guy wires and

fouling the surface search antenna. Four pedestal mounts for the propeller

shaft bearings were cracked. The after mounts of two of the four generators

were fractured. Mercury was washed out of the bowl of the master gyro

compass in Central Station, splashed onto electrical connections and badly

overloaded the circuits. Eight fuel tanks were ruptured, and 150 tons of

salt water flooded into the torpedo blister through the breaks in the skin

in the ship. A few guns lost electrical power. Loose gear flew, and secured

gear broke loose and fell on men below, as the massive flexural vibrations

whipped through the ship.

Stafford makes a few negative comments about Japanese kamikaze pilots that

reflect attitudes of many American veterans and citizens when the book was

published in 1962. For example, "There was something inhuman, something

homicidally insane, about the Kamikaze, which violated the instincts of the

American sailors" (p. 443). In another place, he refers to "fanatical,

half-trained pilots" in the Kamikaze Corps (p. 482).

In August 1945, Navy Secretary James Forrestal praised the aircraft carrier

Enterprise as "the one ship that most nearly symbolizes the history of

the Navy in this war." The many feats vividly described in The Big E demonstrate

why the ship deserved such acclaim.

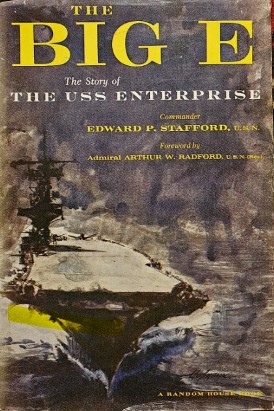

Hardback cover of Random House's

original publication in 1962

|