|

|

|

|

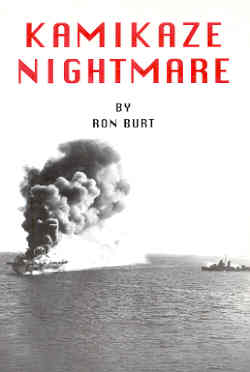

Escort carrier Ommaney Bay on fire after crash by

kamikaze

|

|

|

Kamikaze Nightmare

by Ron Burt

Alfie Publishing, 1995, 218 pages

Thunder and unexpected noises triggered flashbacks of the

"kamikaze nightmare." Pete Burt would shout out "DUCK!" and

then dive under furniture. In the late 1950s, over a decade after going through

four kamikaze attacks, he had a nervous breakdown as he continued to experience

the kamikaze nightmare. Pete suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder for

more than three decades after the war until he experienced his final flashback

in 1977. This book written by his younger brother, Ron Burt, tells the intense,

emotional story of Pete's survival and eventual recovery from a kamikaze attack

that left him unconscious for seven days and required fifty operations over two

years.

Ron Burt, who admits up front to not being

a professional writer, dedicated this book to his brother Pete and to his

shipmates on the escort carrier Ommaney Bay

(CVE-79)

and the light cruiser Columbia (CL-56). Ron Burt

spent several years researching records and trying to contact eyewitnesses to

piece together what caused the kamikaze nightmare. The book starts with some of

their childhood experiences together. As a high school student, Pete enlists in

the Navy at 16 by altering his birth certificate to meet the minimum age

requirement of 17. He becomes a gunner on the escort carrier Ommaney Bay,

where he experiences his first battle engagements

in the fall of 1944 as his ship provides direct air support for the invasion of

Palau and Leyte.

On December 15, 1944, Ommaney Bay's gunners shoot

down an approaching kamikaze plane, which crashes into the water near the ship.

On January 4, 1945, a Japanese Ki-43 Hayabusa (Oscar) hits the ship, and

both of the plane's bombs penetrate the flight deck with violent explosions that

set fire to fully-gassed planes on the hangar deck and that cause water

pressure, power, fuel oil pumps, and bridge communications to fail. The men

below deck have no warning of the incoming plane, and men soon begin to abandon

the blazing ship. Although nearby destroyers pick up over 800 men in the water,

92 men are killed or missing in the sinking of Ommaney Bay.

Pete Burt survives the kamikaze attack on Ommaney Bay,

and he next gets assigned as a lookout on the light cruiser Columbia. On

January 5, the day after being rescued from the water, he watches as kamikaze

planes smash into four other ships. On January 6, a kamikaze plane with an

armor-piercing bomb hits Columbia, causing 41 deaths and 35 wounded (pp. 114-5) [1]. On the same

day, the ship's gunners shoot down three other oncoming Japanese planes after

this deadly attack, and another kamikaze plane nearly misses the ship, spraying

fuel all over the bridge. On January 9, the day that the U.S. invades Luzon from Lingayen Gulf, a Zero

fighter with two 250-kg bombs crashes into Columbia

only 25 feet from where Pete Burt is standing. He describes what happens next

(p. 135):

The explosion carries me thirty feet into a life line. My

body burns with hot shrapnel covering me from head to foot. My left arm is

practically blown to pieces. The muscle rips out from the elbow to my shoulder

exposing broken bones. Hanging halfway over the life line, I lay stunned as

numbness comes over my entire body.

Pete survives but loses consciousness for seven days. The Columbia

suffers 24 dead and 97 wounded from the attack. The last part of the book

covers Pete's long recovery from the kamikaze nightmare, and the final chapter

tells about the his brother Ron's search, starting in 1989, for information and

eyewitnesses about his brother's wartime experiences.

|

|

Kamikaze plane

plunges toward Columbia

on January 6, 1945

|

|

|

|

Numerous remarkable, moving personal accounts from Pete Burt and his

shipmates fill this book. These stories give readers some idea of the great

terror and damage caused by kamikaze attacks. For some events such as the

kamikaze hit on Ommaney Bay, several survivors describe the same event as

they experienced it individually. This technique by the author reveals the utter

confusion and panic experienced by the men below deck who had no warning of the

attack. In another example (pp. 113-4, 142), after the kamikaze hit Columbia

on January 6, the captain gives the order to seal off several compartments

to prevent fire from reaching the ammunition stores. Tears pour out of Pete's

eyes when he realizes the compartments contain two Ommaney Bay

survivors. The 17 dead seamen trapped in the sealed compartments do not get

removed until Columbia returns to Pearl Harbor for repairs.

Possibly to bring some type of closure to the nightmare

suffered by his brother, the author makes a few statements and

conclusions that do not seem supported by available evidence. For example, Ron

Burt states without qualification that the pilot who attacked the Columbia

was Shigeru Kojima. However, a representative of the Japanese National

Institute for Defense Studies wrote in a letter to Burt, "As you know, it

is very difficult to determine who struck what ship in kamikaze suicide attack

especially in 1945, . . . " (p. 202). Seven pilots of Zero fighters

died in kamikaze attacks on January 9, 1945, in Lingayen Gulf (Tokkōtai

Senbotsusha

1990, 143; Hoyt 1983, 165), but Burt concludes on the identity of the

pilot based only on limited information in the letter.

Even more incredible is the author's conclusion regarding

the hairstyle of the kamikaze pilot who attacked Columbia. Pete Burt

claimed for several decades that the pilot was a woman, so his brother Ron tried

to investigate why he would make such a claim. Pete describes the approaching

kamikaze pilot, "Here is this Jap Zero coming at us. Fire from the engine

streams along both sides of the fuselage. The Zero is only about fifty feet

above the surface of the water. I observe all of this in just a matter of a

split second. The pilot and I look at each other" (p. 134). The representative

of the Japanese National Institute for Defense Studies also wrote to Ron Burt

that Japanese warriors in the past wore their hair long, but Imperial Navy and

Army soldiers almost always had their hair cut short. Some pilots were permitted

somewhat longer hair. Based on this very limited information and from the "split

second" observation of his brother, Ron Burt makes the claim that the kamikaze

pilot, Shigeru Kojima, allowed his hair to grow long after being assigned to a

kamikaze unit. Burt alleges (p. 132) the pilot's "hair protrudes several inches

below the helmet" and "hangs almost to his shoulders," but no evidence exists

other than his brother's memory of a fleeting glance at the pilot before he

crashed into Columbia.

The American eyewitnesses to the kamikaze attacks provide

other interesting insights in this book. The U.S. Navy men in the Philippines

referred to the kamikazes as "suicide planes," since at that time

they did not know the name given to the pilots by the Japanese. Before Pete

Burt experienced any kamikaze attacks, he and his shipmates used to discuss the

safest place on a ship when a kamikaze hit. The general consensus was that

every inch of the ship was vulnerable, so the kamikaze nightmare constantly

haunted the American fleet in the first part of January 1945.

Kamikaze Nightmare

not only tells about the damage and terror inflicted on the American fleet off

the Philippines but also the tragedy and ultimate recovery of a man who

suffered his own personal kamikaze nightmare.

On July 10, 2023, the Naval History and Heritage Command published the

following article, "Wreck

site identified as World War Two carrier USS Ommaney Bay (CVE 79)."

Note

1. The entry for USS Columbia in the

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships states that 13 were killed and 44

were wounded, but these figures may refer to only the casualties from the second

kamikaze plane to hit the ship on January 6, 1945, rather than both planes.

Sources Cited

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Department of

the Navy, Naval Historical Center. Web site: <http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/>

Other web site: <http://www.hazegray.org/danfs/>

(June 3, 2007) (link no longer available).

Hoyt, Edwin P. 1983. The Kamikazes. Short Hills, NJ:

Burford Books.

Tokkōtai Senbotsusha Irei

Heiwa Kinen Kyōkai (Tokkōtai Commemoration Peace Memorial Association). 1990.

Tokubetsu Kōgekitai (Special Attack Corps). Tokyo: Tokkōtai Senbotsusha

Irei Heiwa Kinen Kyōkai.

|