Kuroshio no natsu: Saigo no shin'yō tokkō (Kuroshio summer: Last

shin'yō special attack)

by Eidai Hayashi

Kōjinsha, 2009, 277 pages

Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan by radio message at noon on

August 15, 1945. At about 7 p.m. on the following day, several huge explosions

at the Navy's shin'yō explosive motorboat base in Yasu Town (now part of Kōnan

City) of Kōchi Prefecture killed 111 men (including 23 shin'yō crewmen) in the

128th Shin'yō Special Attack Squadron and

wounded many others.

The book Kuroshio no natsu: Saigo no shin'yō tokkō (Kuroshio summer:

Last shin'yō special attack), published in 2009 more than 60 years after the

event, investigates in detail the following questions: Why did the accident

occur at Yasu? What was the source of a report that the enemy fleet was heading

north toward the Japanese main island of Shikoku? Why did the young shin'yō boat

crewmen prepare to sortie? This historical study on a little known

incident delves deeply to find the answers to these questions, but ultimately

many uncertainties remain about what exactly happened and what led up to the

accident.

The author Eidai Hayashi interviews many Shin'yō Special Attack Corps

survivors and other accident eyewitnesses in his search for answers to what

happened at Tei Base in Yasu Town. The interviewees include several Japanese Navy veterans who served

at shin'yō bases other than Tei Base. He also consulted numerous

written sources in his research as evidenced by about 50 works listed in the

bibliography. Hayashi has authored many books related to Japan's wars and former

colonies such as Taiwan and Korea, and he is the recipient of several literary

awards. His prior publications include two well-researched books about Japan's

tokkōtai (Special Attack Forces): Jūbaku tokkō sakuradan ki (Heavy

bomber Sakura-dan special attack plane) (2005) and Rikugun tokkō shinbu ryō: Seikansha no

shūyō shisetsu (Army special attack Shinbu barracks:

Detention facility for survivors) (2007).

The author in the beginning does not clearly lay out either the book's purpose and

scope or the methods he used to obtain information, but the book cover gives

the main questions he tries to answer in the book. However, even despite these

main questions, some parts of the book seem to have little relationship with the

explosions at Tei Base that killed 111 men. However, most of these parts not

related to Tei Base will appeal to someone interested in Japan's Shin'yō Corps as

Hayashi covers details of other shin'yō bases located in Kōchi Prefecture.

A two-page insert in front has historical photos of the plywood shin'yō boat,

which had a one-man Model 1 and a two-man Model 5. The shin'yō boat was powered

by a truck engine, and it carried 250 kg of explosives in its bow. The boats were

suicide (special attack) weapons in which crewmen lost their lives as the boats

exploded when hitting enemy ships. The book includes over 30 other photos

of shin'yō squadron members, current locations of the shin'yō bases, and other

subjects.

|

|

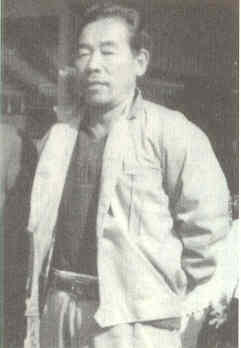

Toyoji Kunita, former 128th Shin'yō Squadron member who received

serious injuries from fire at Tei Base in Yasu Town. Author Eidai Hayashi

could not interview Kunita since he had passed away before the start of the

research.

|

|

|

|

The book's contents are organized clearly into six chapters with each chapter

divided into several parts. After an Introduction that gives a background on

shin'yō bases in Kōchi Prefecture and a summary of the accidental explosions at

Tei Base in Yasu Town on August 16, 1945, Chapter 1 presents the shin'yō special

attack weapon and general background on shin'yō crewmen. Almost all crewmen

received their training at Kawatana Torpedo Boat Training School in Nagasaki

Prefecture. The young men selected to become shin'yō crewmen were

almost all aspiring aircraft crewmen of 17 and 18 years of age in the Navy's Yokaren

(Preparatory Flight Training Program) at Tsuchiura Air Base and Mie Air Base.

Chapter 2 introduces several shin'yō bases that were established in Kōchi

Prefecture on the Japanese main island of Shikoku. Each squadron with about 150

to 200 men was assigned to a single base along the coast. Each squadron had

either about 50 Model 1 one-man shin'yō boats or about 25 Model 5 two-man

shin'yō

boats, so the number of shin'yō crewmen totaled about 50 for each squadron. In

addition to the 128th Shin'yō Squadron at Tei Base in Yasu Town, this chapter and

the rest of the book covers in some detail the following squadrons: 49th Shin'yō

Squadron at Nomi Base, 50th Shin'yō Squadron at Usa Base, 127th Shin'yō Squadron

at Urato Base, 132nd Shin'yō Squadron at Koe Base, and 134th Shin'yō Squadron at

Kashiwajima Base. Tunnels were dug in the rocky hills and cliffs surrounding the

bay where each squadron was located in order to hide the shin'yō motorboats from

detection and attack. The chapter provides maps of the different shin'yō bases

that show the location of the tunnels. There is also a detailed

explanation of the organizational structure of the shin'yō bases, since this has

importance in trying to understand the source of miscommunications that took

place on the day of the explosions at Tei Base. The Kure Naval District's 8th Tokkō (Special Attack) Sentai based

at

Saeki in Ōita Prefecture included two Totsugeki Units based in Kōchi Prefecture:

the 21st with headquarters in Sukumo and the 23rd at Susaki Bay. Tei Base, along

with bases at Nomi, Usa, Urato, and Muroto, were part of the 23rd Totsugeki Unit

in the northern part of Kōchi Prefecture. The 21st Totsugeki Unit included

shin'yō bases in the southern part of the prefecture and also included some bases

in Ehime Prefecture. The 128th Shin'yō Squadron at Tei Base had 171 total members

including 7 officers, 48 crewmen, 31 maintenance workers, 14 headquarters

personnel, and 71 other base workers.

Chapter 3 discusses the situation with the various shin'yō squadrons in Kōchi

Prefecture after the Emperor's announcement of surrender on August 15, 1945.

Orders came from the 23rd Totsugeki Unit headquarters for the squadrons to be

ready to sortie against enemy ships, since there was still a fear that the

mainland could be subject to an imminent enemy attack. The five squadrons in the

21st Totsugeki Unit are thought to have been in much the same situation as they

were ready to sortie in their shin'yō motorboats whenever an order would come.

The young crewmen had been ready to die in shin'yō boat attacks when the

Emperor's radio message of surrender was heard. Many of them at various bases

after drinking that night made comments among themselves that they still wanted

to sortie in order to make suicide attacks. The officers at Koe Base had to order crewmen

of the 132nd Shin'yō Squadron in Tosashimizu to halt such plans to sortie as a group and remain

on alert to be ready to sortie if orders were given.

Chapters 4 and 5 represent the heart of the book where Hayashi addresses

the questions posed on the book cover. Chapter 4 starts with the official

account of the accident as published in the Yasu Town History, which states that

during the afternoon of August 16 an order by telegraph arrived: "The enemy

task force is heading toward Tosa to land on the home islands, so immediately

make preparations to sortie." All squadron members took their boats from the

tunnels and lined them up along the shore, but when the engines were being

adjusted, spilled gasoline suddenly ignited and one of the boats burned up.

Orders were given for the men to take cover. There were attempts to put out the

fires and to return to the boats after a few minutes when it seemed safer, but

the boat fuel tanks overheated and caused huge explosions. This accident

destroyed 23 of the squadron's 25 Model 5 two-man shin'yō motorboats, and 111 men

died along with many injured. Hayashi then summarizes the results of several

personal interviews of the few squadron survivors and other eyewitnesses still

living. The eyewitnesses have some discrepancies between their stories, but they

talk mostly consistently of multiple explosions, the smell of gasoline in the

air, and running to a nearby tunnel to take cover. The author repeats several

times in the book that the Navy never conducted an official inquiry as to what

happened at Tei Base, which probably was due to the state of confusion that

existed within the Navy right after cessation of hostilities. The two survivors

who knew the cause of the fire before the explosions had both passed away by the

time that Hayashi started his research on the shin'yō boat accident at Tei Base,

so it appears that the cause can never be known with certainty.

|

|

|

|

Shigeo Nagoya, former 128th Shin'yō Squadron

member who drove men seriously wounded in Tei Base explosions to the

Japanese Red Cross Hospital in Kōchi City.

|

|

|

Chapter 5 presents several different incorrect reports related to the

accidental explosions at Tei Base. One was the supposed sighting of the

enemy fleet, but the original source of this report is not clear, and naval

reconnaissance flights from Kōchi Air Base did not confirm this sighting. Another false report

indicated that the masts of 13 enemy warships, which appeared to be cruisers, had

been sighted 25 kilometers south of Kōchi City. This message came by urgent

telegraph from Kōchi Naval Air Group to the 23rd Totsugeki Unit headquarters

in Susaki before 6 p.m. on August 16, 1945. Therefore, when pillars of fire were

sighted in the direction of Yasu Town, the 127th Shin'yō Squadron members at

Urato Base initially thought in

error that

the enemy bombardment had begun and that their shin'yō motorboats would sortie

soon to attack enemy ships off Shikoku

Island. In another incident, the 134th Shin'yō Squadron at Kashiwajima Base along

with the 21st Totsugeki Unit in Sukumo did not clearly understand the Emperor's

message of surrender, so they remained ready to sortie. Coincidently, an accident

similar to the one at Tei Base occurred at Kashiwajima Base at about the same

time. Gasoline apparently caught

fire at Kashiwajima Base and led to an explosion in one of the tunnels, but this accident destroyed

only three shin'yō boats and slightly injured one person in comparison to the Tei

Base accident with 111 men killed, many injured, and 23 boats destroyed. This

chapter also goes into theories behind the mysterious disappearance of

Lieutenant Junior Grade Seisaku Takenaka, commander of the 128th Shin'yō

Squadron, during and after the explosions at Tei Base, but a definitive

conclusion is never reached, although we know from the book's last chapter that

he was not injured and returned home to Ōsaka soon after the incident.

Chapter 6 covers the repatriation of shin'yō squadron members. Parents who

heard the news of their sons' deaths had a difficult time in understanding why

they were killed in such an accident when the Emperor already had declared an

end to the war on the previous day. Each year there is an annual memorial

service at Yasu on August 16 to remember the 111 men who lost their lives in the

accidental explosions. A monument was erected on the former base site on August 16, 1956,

but Hayashi points out that the history engraved on the monument contains

several mistakes. For example, the monument states that 111 men of the 9th

Shin'yō Squadron lost their lives on August 16, 1945, but actually the correct

squadron is the 128th Shin'yō Squadron. Apparently the person who wrote the

history for the monument mistakenly picked up "9th" from the 9th group of

shin'yō

squadrons formed at Kawatana Torpedo Boat Training School. Squadron leader

Seisaku Takenaka had the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade, but the monument

history incorrectly states his rank as Lieutenant.

This thoroughly researched book demonstrates how difficult it can be to

conclude with any degree of certainty what happened exactly in a specific

historical incident, especially when most of the eyewitnesses have passed away.

Related Web Pages

Shin'yō Corps monument to the 111 men

who died for their country at Tei Base

(in former Yasu Town, Kōchi Prefecture)

|