Firipin shōnen ga mita kamikaze: osanai kokoro ni kizamareta yasashii

nihonjintachi (Kamikaze seen by Philippine youth: Kind Japanese individuals

engraved in my young heart)

by Daniel H. Dizon

Sakuranohana Shuppan, 2007, 353 pages

Daniel Dizon, born in 1930, met several kind Japanese soldiers and airmen

during his youth when Japan occupied his home country, the Philippines, for just

over three years starting soon after the initial attack on December 8, 1941. The

first half of this Japanese book tells his childhood experiences during the war with his

family in Pampanga Province, and the second half describes his postwar

activities and his opinions on a variety of

subjects such as the reasons why Japan instigated a war. This book written in

Japanese provides no background information as to how Dizon, who does not know

the Japanese language, came to be the author. When asked about this in an

interview in October 2009, he explained that two persons came from Japan to his

home in Angeles City to interview him each day for a couple of weeks in order to

gather material to ghostwrite his autobiography.

The question arises as to the objectivity of this book, actually written by

Japanese individuals, about the positive impressions that Dizon had of Japanese

military men during WWII. However, the story seems to be honestly told without

any blatant attempt to convert the book into a propaganda piece. Dizon clearly

has strong positive opinions about Japanese people he met during the war, which

differ from those of many of his countrymen. However, he does not try to hide

negative acts by the Japanese military, such as a massacre of about 300

Filipinos including women and children, carried out by Japanese troops near

Angeles early in the occupation. Dizon's father, a painter who graduated from

Yale University and had many American friends, generally held a negative view of

the Japanese occupying his country. In contrast, Dizon's independent positive opinions

toward the Japanese seem to have been shaped by his own personal wartime

experiences, regardless of beliefs of family members and fellow

countrymen.

The title of Firipin shōnen ga mita kamikaze (Kamikaze seen by Philippine

youth) does not accurately reflect Dizon's experiences. He met several friendly

Japanese soldiers and airmen, especially early in the Japanese occupation

period. However, he never met a kamikaze pilot during the war, since Vice

Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi formed the first kamikaze unit in October 1944 as the

Allies were invading Leyte, and the kamikaze pilots flew from Philippine

airfields for less than three full months through January 1945. Dizon lived in

an area with many Japanese airfields, including Mabalacat from where the first

official kamikaze squadrons made sorties, but Japanese kamikaze airmen had little or

no time to socialize with the local people during this period when they needed

to prepare quickly for their missions against the invading Allies.

Dizon's deep interest in the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps began in 1965 when

he read an English translation of The Divine Wind (1958) by Captain Rikihei

Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima. The American military personnel who

came to his hometown of Angeles in 1945 talked about Japanese suicide squadrons, but Dizon did

not know anything more about them despite living close to airfields

from which many kamikaze pilots took off. The stories and last letters of

kamikaze pilots included in The Divine Wind left a great impression on him, and he strongly felt that he had

to do something so that Japanese kamikaze pilots could be remembered in the

Philippines. Other Filipinos expressed little interest, but finally in 1974 he

convinced local tourism officials to erect a monument to the Kamikaze Corps at

the former site of Mabalacat East Airfield. The monument had a sign in English with the

words "Kamikaze First Airfield Historical Marker" and had an inscription in

Japanese with the following words, "Airfield where Kamikaze Special Attack Corps

aircraft first took off in World War II."

After erection of the kamikaze monument in Mabalacat, several Japanese people came

to visit Mabalacat and meet Dizon including the widow of Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi and Saburō Sakai, one of Japan's greatest fighter pilots. During the

1970s and 1980s, Dizon gathered information about kamikaze pilots in the

Philippines and collected Japanese military weapons and equipment that later

became part of exhibits displayed in the Dizon Kamikaze Museum, located in a

large room at his home in Angeles City. However, the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo

nearly buried the kamikaze monument in ash. Dizon explained the historical

importance of a new memorial to officials at the Mabalacat Tourism Office, and a

new monument with the Japanese and Philippines flags engraved on a wall was

erected in 2000 at the same site as the original kamikaze monument. In 2004, a

kamikaze pilot statue was erected in front of the wall.

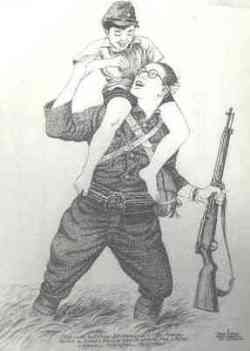

Dizon playing with Army Sergeant

Yamazaki, who taught Japanese

at school (illustration by Daniel Dizon)

Dizon also urged that a monument be erected at the site of Mabalacat West

Airfield, since this was the actual location from where the first kamikaze

squadron led by Lt. Yukio Seki took off on October 21, 1944, but had to return

to base when no enemy ships could be located. In 2004, the

Mabalacat West Airfield

Monument was erected, and the Japanese words on the top of this monument are the same

as those from the original buried monument at Mabalacat East, "Airfield where

Kamikaze Special Attack Corps aircraft first took off in World War II." Dizon's

many efforts to remember the Japanese kamikaze have attracted some controversy in the

Philippines and other countries as certain people believe the Philippines should

not have such monuments to remember the Japanese military, which brutally

occupied the country for about three years. For many years Dizon has defended

his fervent admiration of the Japanese kamikaze pilots' bravery and dedication

in statements such as the following (p. 252), "If proof came out that even just

one kamikaze pilot committed an atrocity against Filipino civilians, then I

would immediately tear down the kamikaze monuments."

The first five chapters cover Dizon's life in roughly chronological order.

Chapter 1 describes how he viewed the

Americans, who occupied the Philippines prior to the Japanese occupation, as heroes especially through the

influence of American comics. Chapter 2 covers the Japanese invasion of the

Philippines from the first attack on December 8, 1941, to the surrender of the

Americans at Bataan in April 1942. He met kind Japanese soldiers who taught

Dizon and other children Japanese songs and who really wanted to learn English

to communicate. He describes a soldier named Takemoto who stopped by his

family's home for lunch with a truck carrying American and Filipino POWs from

Bataan, and he allowed his family to give food and drink to the prisoners. The

stories in Chapter 3 take place during the Japanese occupation of the

Philippines. The Dizon family lived in the center of Angeles Town near a

Japanese base, so Daniel Dizon had many opportunities to make friends with Japanese

soldiers. Dizon, who displayed artistic talent even as a child, drew portraits

of some soldiers stationed at Angeles.

The episodes in Chapter 4 describe the dismal state of affairs of the

Japanese military during the last stage of the war in the Philippines. The book

devotes quite a few pages to the story of a Philippine family that sheltered a

Japanese soldier name Butcho. He deserted from the Army and became like a son to

the Philippine family. Eventually the family was forced to hand him over to the

Americans, and the family never heard from him again. Chapter 5 covers Dizon's postwar activities including his appeals to build kamikaze

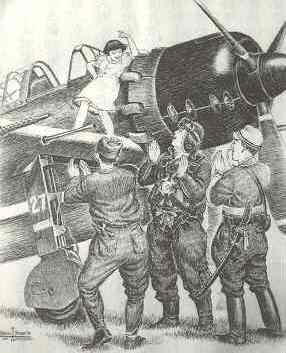

monuments in the Philippines. Dizon's wife Enriqueta tells her wartime stories

in Chapter 6. As an eight-year-old girl, she worked pulling weeds at Porac

Airfield near Angeles from April to September 1944. She knew many Japanese songs

from school, so a Navy officer often asked her to sing and dance on the wings of

a Zero fighter. The chapter includes a drawing by Dizon depicting this wartime

scene (see below). In total, the book includes about a dozen of Dizon's historical

illustrations of wartime scenes and persons during the Japanese occupation. The

book's last two chapters contain sections on a variety of topics with Chapter 7

focusing on why Japan started the war and Chapter 8 explaining Dizon's desire

for true friendship especially between Japan and the Philippines.

Enriqueta (Dizon's wife) singing and

dancing on wing of Zero fighter

(illustration by Daniel Dizon)

The many individuals in the Japanese military portrayed in this autobiography

provide a distinctive depiction of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. The

book also includes about 20 pages of historical photos from both during and

after the war. Daniel Dizon is sympathetic in his portrayal of Japanese military

men and seems supportive of certain arguments supported by Japanese

nationalists. However, he points out some atrocities committed by the Japanese

military during the occupation, but he also calls attention to brutal acts by

Americans and Filipinos. Despite years of opposition and ridicule by many

countrymen, Dizon has remained deeply impressed by the kamikaze pilots'

spirit and courage, and he has held firm in his strong independent beliefs

concerning the historical importance of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps to the

Philippines.

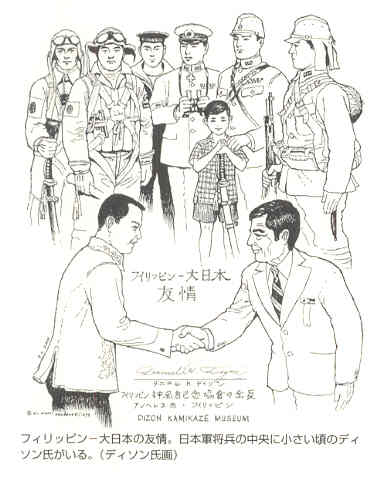

Friendship between Philippines and Greater Japan.

Dizon at young age is in center among Japanese

officers and men. (illustration by Daniel Dizon) |