Advance Force Pearl Harbor

by Burl Burlingame

Naval Institute Press, 1992, 481 pages

Many books have been written about the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor, but few give much attention to the role that Japanese submarines

played in the attack. The title of Advance Force Pearl Harbor suggests

this book will tell the history of the 25 Japanese submarines, including five

with attached midget submarines, in the Advanced Expeditionary Force that

participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The book does cover this subject

quite thoroughly, although in a disjointed fashion, but the topics discussed in

this history at times stray far afield from the title.

Burl Burlingame, journalist with the Honolulu

Star-Bulletin since 1979, has been interested in the Pearl Harbor attack

since childhood, when he started to read everything he could find about the

incident. This thoroughly researched book contains an extensive bibliography of

primary sources and over 300 photos and diagrams. Although Advance Force

Pearl Harbor has some drawbacks in organization and focus, the book contains

the most thorough coverage on Japanese submarine involvement in the Pearl

Harbor attack of any English-language book published to date.

The author devotes many pages to the preparation, execution,

and aftermath of the five midget submarines' operations during the Pearl Harbor

attack. This topic extends from the first chapter to the last one, but much of

the book's other material deals with battle action that occurred far away from

Pearl Harbor or long after the attack on December 7, 1941. For example, one

chapter near the end includes several pages about the March 1944 slaughter of

civilian sailors aboard the Dutch freighter Tjisalak carried out by the

I-8 submarine, which participated in the Advance Force for the Pearl Harbor

attack. The scope of the book becomes less focused in the last half, which

includes topics such as Japanese submarine attacks off the U.S. West Coast and against small, far-flung Pacific islands.

The huge number of names, places, ships, and events makes

this book difficult to read in places. In addition, the author often breaks up

longer stories into several pieces and includes many pages of unrelated

material in between these parts. This technique makes it even more difficult to

follow a narrative involving many people and other details. For example, the

story of the sinking of the freighter Lahaina by the Japanese I-9

submarine on December 11, 1941, and the survival of 30 men who reached Hawaii

after ten days in a lifeboat gets divided into three major parts with dozens of

pages in between (pages 146-7, 293-9, 336-7).

Advance Force Pearl Harbor includes many personal stories of Japanese and

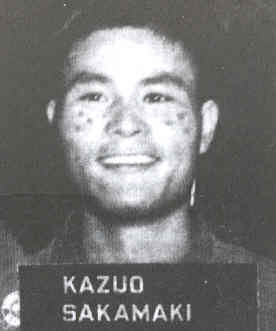

American participants at Pearl Harbor and later in the war. Kazuo Sakamaki, the

pilot of one of the midget submarines and America's first POW of WWII,

receives attention throughout the book. Chapter 5 introduces each

crewmember of the five two-man midget submarines that participated in the Pearl

Harbor attack. Chapter 11 describes the release of the midgets from the mother

submarines carrying them and includes the last writings of some of the

crewmembers, including the following poem by Lieutenant Naoji Iwasa:

As the cherry blossoms fall

At the height of their glory,

So, too, must I fall

That men may call me

A flower of Yamato,

Though my bones lie scattered

In the bleak wilderness

Of strange and distant lands.

Chapters 12 to 19 constitute the heart of the

book with a description of battle action of Japanese submarines and

American warships around Pearl Harbor. Sakamaki's midget had several mechanical

problems, including a non-functioning gyrocompass, so he and his crewman

Kiyoshi Inagaki could not control its direction. They eventually abandoned the

midget after setting explosives to scuttle it, but they failed to explode. The

small craft ran aground and was recovered so that Navy Intelligence could

investigate this Japanese secret weapon and its contents. Inagaki died on the

way from the midget submarine to the shore, but Sakamaki was captured after

washing up on the beach.

|

|

POW Kazuo Sakamaki

with cigarette burns on cheeks

|

|

|

|

Nobody knows exactly what happened to the other four midget

submarines after release from their mother ships since no crewmember survived.

The book's narrative does not clearly describe the fate of each midget submarine,

but Burlingame in 2002 wrote an article entitled "First to Die"

in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin that summarizes the current status of historical

research related to these four midget submarines. More than one hour before the

aerial attack on Pearl Harbor at 6:45 a.m., the destroyer Ward (DD-139)

fired the first shot of the Pacific War at the conning tower of one of the

midget submarines. Ward dropped depth charges that sank the midget

(according to 2002 article, most likely the one piloted by Ensign Akira Hiroo

from the I-20 mother submarine). Within an hour after the first Japanese planes

attacked Peal Harbor, the destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) rammed a midget

submarine inside the harbor after the midget fired two torpedoes. Subsequent

depth charges succeeded in sinking it (according to 2002 article, most likely

the one piloted by Lieutenant Naoji Iwasa from the I-22 mother submarine). In

1960, another midget submarine (according to 2002 article, most likely the one

piloted by Lieutenant Junior Grade Shigemi Furuno from the I-18 mother

submarine) was recovered from Keehi Lagoon and is now on display outside the

Etajima Museum of Naval History. The last midget submarine, piloted by

Lieutenant Junior Grade Masaharu Yokoyama from the I-16 mother submarine, has

not yet been discovered. However, Chapter 15 has a very interesting photo and

an enlargement of a section of the photo that may show a midget submarine

firing a torpedo during the aerial attack. Burlingame speculates in his 2002

article that this may have been the I-16 midget submarine. On December 8 after

midnight, Yokoyama radioed the message of "successful surprise

attack" to the I-16 mother submarine, but it is not known what happened to his midget

submarine after radio communication ceased at 1:11 a.m.

The nine crewmen to die in the five midget submarines that

attacked Pearl Harbor were the first members of Japan's Special Attack Forces.

The phrase "special attack" in Japanese indicates the suicidal nature

of their mission, and much later in the war the Special Attack Forces included

other suicidal weapons such as kamikaze planes, kaiten human torpedoes, and

explosive motorboats.

Admiral Yamamoto wanted provisions to be made for the rescue of the midget sub

crews, and the mother submarines that carried the midgets were to wait at a

rendezvous point seven miles west of Lanai. However, the designation of the

five midget subs as a Special Attack Flotilla and the crewmen's writing of last

letters to their families showed that they had almost no hope of survival.

Kazuo Sakamaki felt that he had failed in his responsibilities. Upon

his capture, he said that he wanted to commit suicide as the honorable

act for a Japanese Naval officer, and he wrote on December 14, 1941, as part of

a long letter, "Thus I betrayed the expectations of our 100,000,000

(people) and became a sad prisoner of war disloyal to my country." Before

getting his POW photograph, he pressed a lit cigarette into his cheeks and

branded six small circles on his skin making the shape of a triangle on each

cheek. He stayed in various POW camps on the mainland U.S. until the end

of WWII. After the end of the war, Sakamaki joined Toyota as a clerk and

eventually became an

executive and the head of Toyota's subsidiary in Brazil.

The nine midget submarine crewmen who died were

promoted two ranks and were honored as war gods. The Japanese propaganda

machine could make public the previously unknown secret weapon since Sakamaki's

midget had been captured. Many Japanese Naval leaders had been against

deployment of the midget submarines, since they could have alerted Americans of

an impending attack. Despite the glory bestowed by the Japanese press on the

Special Attack Flotilla members for their heroics at Pearl Harbor, they had

little or no battle success even though Japanese propagandists attributed

battleship USS Arizona's

sinking to a torpedo fired from one midget submarine. In the book's last chapter,

Burlingame summarizes the reasons for the midgets' lack of success: "The

midget submarines failed at Pearl Harbor due to a triple-punch. Their own

inexperience and too-brief training period, Pearl Harbor's difficult waterways

and the alert, dogged response of American destroyers mitigated against

success."

|

|