|

|

|

|

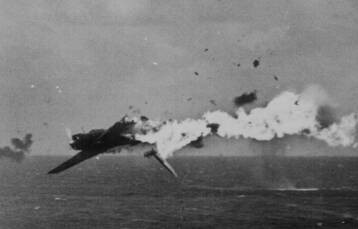

A Jap torpedo bomber breaks apart in flaming ruin while

attempting to crash-dive the carrier Yorktown in the battle of the Philippine

Sea.

(caption from original article)

|

|

|

Japan's Last Hope

by Irving Wallace

Introductory Comments

This article first appeared in Liberty magazine on May 5, 1945.

Although Liberty stopped publication in 1950, at its peak it was ranked

alongside The Saturday Evening Post and Collier's as one of the

top three American feature magazines.

Irving Wallace, a prolific author of both fiction and non-fiction, worked in

the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II. This article, an exclusive from the

U.S. military, was the first big national write-up about Japan's kamikaze

attacks. The following paragraph describes how Wallace got this exclusive for Liberty

magazine (Wallace 1978, 136):

Wallace was privy to the Kamikaze information because at the time he was a

writer for the U.S. Signal Corps under Frank Capra. The Kamikaze material had

been monitored by the Signal Corps from Tokyo radio, translated, and

circulated in the military as classified material. Wallace says that when it

came across his desk, "I saw that it was tremendous stuff. I asked my

superior officers if I could write an article at night—on my own time—on

it. They said yes, and that's how Liberty got the beat."

Casting about for a last desperate weapon to stem the tide of defeat, Tokyo's

war lords have come up with something that goes Hitler one better—human robot

bombs

Radio Tokyo is on the air.

"News flash! News flash from Tokyo! The Imperial

Headquarters announced at two thirty o'clock this afternoon that the Kamikaze

Special Attack Corps has sunk one American battleship, three large transports,

and damaged one battleship or cruiser in Leyte Gulf.

"Our six fliers successfully penetrated enemy

fighter-plane defenses and headed for enemy transports, which were escorted by

battleships and cruisers.

"One of our planes plunged into an American battleship,

and just as the big ship shook from the impact, a second plane crashed into it.

A huge fire soon enveloped the vessel. The four other planes raced toward the

enemy transports. In swift succession they plunged into them, sinking three and

setting ablaze another large ship, which last was seen emitting a pillar of

black smoke.

"Among the six Kamikaze fliers who died in this attack,

three men—Matsui, Terashima, and Kawashima—are not yet twenty years old. The

spirit of these young fliers crash-diving on their objectives is admirable."

This news report—typical of recent daily reports—discloses

Japan's last hope.

With Allied sea and air power slowly strangling Japan, the

Tokyo war lords cast about for some last-resort weapon. They observed that

Hitler had pulled one out of his ordnance hat; but that his V-1 and V-2 robot

bombs, though frightening and damaging, were not enough to stop the Allies.

They decided to go Hitler one better. They had human robot bombs.

Determined to capitalize on the willingness of their young

men to die, the Japanese leaders organized the Navy's Kamikaze Special Attack

Corps. Suicide assaults by Japanese infantrymen and fliers were already

familiar occurrences. But with the Kamikaze, Japan made the first modern effort

by any army or navy to send vast numbers of trained men to premeditated

suicide.

Kamikaze is Japan's god of the wind. The word itself means

"Divine Wind." and it stands for much in Japan. Six and a half

centuries before Nimitz, the mighty Mongol, Kublai Khan, threatened Japan with

300 warships and 200,000 men. At the eleventh hour it happened that a real

wind, a typhoon, bore down on his armada, smashing and sinking it. Ever since,

the Japanese have been taught that when in danger a Divine Wind would save

them.

But this time the Japanese leaders knew they could not

depend on a typhoon. They knew they must create their Divine Wind. And so they

created the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps, dedicated to death—for itself and

Americans.

"Today, each of our planes in this Special Attack

Corps," explains Radio Tokyo, "is piloted by one Kamikaze pilot whose

mission is to crash-dive into a warship or transport with the object of sinking

that ship at the cost of one plane and the life of one pilot. . . . Unlike a

mechanical bomb, the living torpedo that has eyes, ears, and brains behind it

is something that cannot be duplicated by any mechanism."

The Kamikaze Special Attack Corps was first thrown into

action two weeks after General MacArthur waded onto Philippine soil with his

infantry veterans.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, German-educated conqueror of

Singapore and Bataan, opposed MacArthur, proclaiming that the Kamikaze would

turn the trick. Even as Leyte fell, he reassured the folks back home in Tokyo.

"That our forces," he said, "with (comparatively) small strength

and small amount of material supplies, were able to achieve such brilliant war

results is all due to the traditional spirit of offering one's life and

carrying out deliberate crash-dive attacks on the enemy. . . . If one of our

fighter planes should bring down one enemy B-29 by a deliberate crash-dive

attack, it would be proportionately one to ten. Then again, if one plane should

sink or damage one enemy aircraft carrier or one battleship, it would be one to

100, 1,000, or 10,000. No matter how the enemy would come against us with his

superiority in materials, if the enemy is met with this deliberate crash-dive

spirit, then it could be concluded that the enemy could be completely

defeated."

Desperately the Kamikaze pilots catapulted their bomb-laden

planes into our warships and supply ships off Leyte, Mindanao, and Luzon. The

American Navy soberly admitted to some losses. The Japanese ecstatically

claimed half of all our shipping. The truth? There is only one truth. Today,

again, we dominate the Philippines. Today we stand astride the Pacific. Quite

obviously Japan's Divine Wind has not been enough.

Yet there is every indication that Japan will, in the near

future, throw her organized Kamikaze suicide fliers against us in greater

numbers. Admitting shortages in everything else, she finds men ready to die her

cheapest effective weapon. What is more, the Kamikaze has caught on in Japan.

The very latest available Japanese newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, and

reports of neutrals show all Japan in a lather over the Corps' exploits.

Domei, the Japanese official news agency, insists that the

people wish to read of nothing else. Japanese dailies front-page a letter from

Colonel Tatsuhiko Kida in which he revels that "his iron-nerved self-sacrificial

pilots, before leaving base on their sure-hit mission, donated all their pocket

money toward the aircraft-construction fund." Reaction to this propaganda

is instantaneous. The Munitions Ministry shrewdly invests the money in towels.

Each towel, featuring the word "Kamikaze" inscribed over a Rising

Sun, is sent to an aircraft-factory laborer. Production goes up.

At the immense steel factories on Kyushu, heavily bombed by

American B-29s, the directors deliver pep talks on the Kamikaze, then order a

"Crash-Diving Spirit Production Month."

The Nippon Newsreel Company floods theaters with shots of

the Kamikaze heroes. Viewing these films, rich Japanese demand inspiring

pictures of the Kamikaze for their homes, and the government promptly

commissions Nippon's leading artists to immortalize the suicide corps in oils.

The air waves add to the intoxication. One radio program

features Captain Etsuzo Kurihara, chief of the Japanese Navy Press Section.

"War cannot be won by the employment of usual tactics," he says.

"Ramming and crashing are the only tactics which can be effectively

applied against enemy vessels. I feel that the great services of the Special

Attack Corps are too sacred to be put into cold figures, but were we to do so,

we could say that this type of tactics is worth ten to fifteen times the

ordinary tactics."

The greatest lift given the legend of the Kamikaze occurs

every two weeks when Emperor Hirohito receives top-priority heroes in the

Imperial Palace. Just before New Year's Day the emperor permitted Lieutenant

Colonel Tsuneyemon Shindo and Major Torashiro Aizawa to crouch before him.

"How do our airmen compare with the Americans?" he inquired. The

humble officers, eyes averted, whispered that Japanese morale was much the

higher; that "the spirit of the men of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps

has yet to find its equal."

Then, while all Japan thrilled to its emperor's interest in

his lowly subjects, there came another tidbit, of humbler origin but even more

exciting. This one was reported in the daily newspaper Asahi, dated January 12,

1945:

"A small box containing ashes and a portrait,

accompanied by a letter addressed to a certain air unit commander, arrived by

parcel post at the front lines. The sender was one Motoko Kunimitsu of Shiode

village, mother of Sublieutenant Kunio Kunimitsu, who unfortunately was killed

in line of duty last fall at that particular air base.

"The mother's letter reads as follows: 'I have a great

deal of compassion for my son who had his heart set upon becoming a member of

the Special Attack Corps. If it is at all possible, will you kindly allow his

ashes to join the Special Attack units? It is my most sincere desire that his

ashes, at least, carry out a body-crash brilliantly, and as soon as possible.'

"What arduous spirit for the mother to offer her dear

child to decisive battles in the skies! The unit commander was deeply touched

by this letter. So now, hugged snugly in the arms of his comrades, the ashes of

the sublieutenant will take off from the homeland, never to return."

This daily dosage of outrageous hokum not only hypos the

home front, but baits thousands of young men into volunteering for certain

death.

Of course, the basis for the Kamikaze is Japanese

fanaticism. There are many explanations for that. The most satisfactory is

state Shinto, the so-called religion of Japan, the "way of the gods."

Shinto is thoroughly politics, the spearhead of Japanese Fascism. It preaches a

perverse morality that condones rape, murder, the stab in the back. It tells

the Japanese they are the holy people, superior to all others on earth, and

that one day they and their emperor must rule the rest of the civilized world.

Above all, Shinto makes human life cheap, cheering its young men with the

promise, "To die for the emperor is to live forever."

For almost a century the young men of Japan were prepared

for this task of sacrificing their lives to the divine mission of the state. On

the ground, the Japanese soldier dared not retreat. "We do not even have a

bugle call for retreat," a Japanese major told this author in Tokyo a year

before Pearl Harbor. In action, the Japanese soldier had to live the legend of

the three human bombs of Chapei, soldiers who carried dynamite into Chinese

barbed-wire entanglements and blew themselves up with it.

It was not until ten years ago that this suicidal

indoctrination was first channeled into flying. At that time Japanese

militarists toyed with the idea of developing special aviators to plunge

dynamite-packed planes into enemy warships. The plan was shelved, and suicide

crash-dives occurred only when Japanese pilots found their planes shot out of

control. Instead of dumping their bomb loads, they often dived into the nearest

available military objective. Reports on these irregular desperation dives

began to filter back to Tokyo. Japanese leaders learned that often they were

successful. This revived again the old idea of an organized and trained suicide

corps.

The Japanese Navy was the first to prepare such a force.

Drawing 100,000 volunteers from its naval aviation schools, it formed the

Kamikaze Special Attack Corps. A short time later the Japanese Army

carbon-copied the Kamikaze with suicide fliers of their own—the Banda Special

Attack Corps.

The average Kamikaze volunteer, a graduate of the Air

Military Academy, is five feet three inches tall and weighs 118 pounds. He is

between nineteen and twenty-five years of age. Before seeing action, he is put

through a short preparatory course. On the first day of it a movie shows him

how other Japanese heroes have sacrificed themselves for the emperor. He is

persistently lectured on the three qualities each Kamikaze flier must possess:

First, absolute obedience. Second, complete devotion to duty. "This means

intellectual conclusions must not be made." Third, thorough knowledge that

any given assignment must be carried out successfully. "Death counts as

nothing before the importance of the completion of one's duty."

There is an unwritten law that Kamikaze trainees must not

discuss or philosophize on the subject of life and death. They are kept busy:

classes, flying, sports. The favorite sport is kendo, a Japanese pastime

involving two men attired like baseball catchers who belabor each other with

bats. The instructors regard kendo as a good exercise for suicide flying.

"On the moment of clashing in kendo, students are not allowed to close

their eyes. They learn the spirit of killing with certainty."

Most Japanese believe a close relationship springs up

between Kamikaze instructors and their one-shot pupils. Japanese sob sisters

reinforce this belief in the daily press. Recently a Tokyo newspaper, the

Yomiuri Hochi, interviewed Colonel K. Tomomori just after he'd learned that

most of his students had plunged to their death. Said the account:

"Colonel Tomomori's emotion was deep. 'I am overcome by

tears of joy,' he related, as teardrops welled in his eyes."

The first trained Kamikaze fliers went into action off Leyte

in November, 1944, wearing special Rising Sun headbands. These were gifts from

General Gen Sugiyama, War Minister of Japan, who in prewar days forced English

men and women to strip naked in Tientsin. On each band was printed his

farewell: "Congratulations on Daring Enterprise and Sure Victory."

Along with their headbands, the Kamikaze carried into battle

a new song. They were supposed to sing it as they pointed their planes at

American ships. It went:

On land, the Fierce Tiger, General Yamashita;

On sea, Blood-and-Iron Okochi,

Behold the powerful line-up!

The thunder of righteousness makes the world tremble.

Where'er our Special Attack Corps go,

We, the hundred million, follow.

Come on, Nimitz! Come on, MacArthur!

If you do, we'll send you both

Headlong down to hell!

During the first forty-eight days of action off the

Philippines, the Kamikaze and Banda Special Attack Corps claimed the sinking of

113 American supply ships and warships. Since the American Navy did not confirm

it, this figure is not to be accepted as fact.

As the fight for the Philippines progressed, Tokyo's foreign

correspondents' daily reports were all variations on the same theme. In every

story one Japanese plane crashes and sinks an American warship. When the claims

of the Kamikaze are tabulated, it will be found they claim to have destroyed

every ship in the U.S. Navy and merchant marine—plus those scheduled to be

launched up until 1955!

But though the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps failed to save

the Philippines, its units will continue to be utilized to the very end. Its

young men will be thrown into the skies over the Chinese treaty ports, over

Formosa and the Bonins. Most of all, the Kamikaze will be employed against our

warships and bombers as they close in on the Japanese home islands.

In fact, because all else has failed, the Japanese are using

Kamikaze and Banda crash divers over Tokyo in an attempt to halt our B-29s. An

elite air unit called the Shinten, which means "shock troops of

heaven," was organized "for the express purpose of destroying the

B-29, the enemy's vaunted high-speed, high-altitude plane, by crashing into

them." This unit is under the command of General Prince Higashi-Kuni.

Our Army Air Forces have admitted a few losses through

rammings over the Japanese homeland. But the Japanese lavishly claim dozens.

One of their typical claims, dated December 5, 1944:

"Without firing a shot, Corporal Masao Itagaki dashed

against the last plane of a formation of eleven B-29s in the midst of the

enemy's fire net. His plane was hit with bullets and enveloped in flames.

Undaunted, he rammed his plane against the main wing of the B-29, clipping it

off. At that instant he was thrown from his plane. When he regained

consciousness, he found himself under a parachute which had opened up."

The Japanese insist the Kamikaze will save Japan. They say,

from Shanghai's radio station XGRS, "No mechanical device nor invention

exists today in the United States for opposing this Japanese method for

obtaining victory. Therefore the outcome of the war in the Pacific is already

determined in favor of Japan." In the Algemeine Zeitung the Germans echo

this Japanese confidence in the efforts of the Kamikaze.

The Kamikaze won't save Japan any more than it saved the

Philippines. It may cause some damage, some loss of life, but our planes and

carriers and battleships will continue to knock most of these suicide raiders

out of the sky before they complete their missions.

Source

This article comes from a reprint on pp. 137-49 of the following book:

Wallace, Irving. 1978. Some Interesting People and Times.

Edited by Nat LeMar. New York: Dale Books.

|