Nishizawa: Japan's Deadliest Combat Pilot—102 U.S. Air Force Kills

by Martin Caidin

Stag, October 1961, pp. 36, 38-9, 70-3

Introductory Comments

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa is generally acknowledged as the

Japanese WWII fighter pilot with the highest number of kills, although the exact

number varies based on source. This story focuses on dogfights during the

first half of his career with no specific mention of any kills between his total of 52

achieved by November 1942 and his final total of 102 kills when he died in

battle on October 26, 1944.

On October 25, 1944, Nishizawa led four Zero fighters that escorted five

Zeros carrying 550-lb bombs of the first official squadron of the Kamikaze Special

Attack Corps. He volunteered the next day for a suicide mission as a Kamikaze

Corps pilot, but Commander

Tadashi Nakajima refused his request due to his inestimable value as an

experienced fighter pilot.

This historical story differs from other far-fetched

stories about kamikaze pilots published in men's adventure magazines in the

1950s and 1960s. The author Martin Caidin, author of Saburo Sakai's

autobiography entitled Samurai! (1957), depicts accomplishments of Japan's greatest ace who flew together with Saburo Sakai in

many aerial battles, but it is not been verified that the battle details in this

article are accurate.

Stag's magazine cover introduces the story with the following quote:

"I led the greatest kamikaze raid." However, this quote never appears in the

story, and in fact no quote from Nishizawa is in the story. Much of the

information about him in this story comes from his fellow fighter pilot Saburo Sakai.

Notes have been added to the story in order to provide comments on

geographical inaccuracies near the end of the page. Click on the note number to go to the

note at the bottom of the web page, and then click on the note number to return

to the same place in the story.

Leading ace of the Imperial's crack Lae Wing, he made the Pacific his

private battleground and any Allied plane that flew across it his personal

target.

There are ten P-40 fighters in a long column, patrolling at fourteen thousand

feet over the vital New Guinea base of Port Moresby. The formation leader

suddenly sights four Japanese Zeros, two thousand feet lower than his own force.

It couldn't be better. He snaps out his orders. Three fighters are to dive

with him to bounce the enemy; the remaining six P-40s will hold their altitude,

ready to come down at once in case there is trouble. He doesn't expect any.

After all, he is in a perfect position to attack: he holds an altitude

advantage, and he has fast-diving, heavily-armed fighter planes. It's just the

kind of situation that any pilot would want—meat on the table.

Smoothly, functioning as a team, the four P-40s roll on their backs and

plummet toward the Japanese fighters. The plan is simple: as the Zeros scatter,

each P-40 pilot will take one, bounce him hard, and end the battle almost as

quickly as it begins.

But it doesn't happen that way, for the P-40 pilots have run into the worst

hornet's nest in all the Japanese Navy. Those aren't rookies in those Zeros;

they're the best that Japan has ever put into the air. Not only are the Japanese

pilots aces, they are the leading aces of the famed Lae Wing, and the Lae

Wing is the crack outfit of Japan's fighter pilots. The pilot's names:

Nishizawa, Sakai, Ota, and Takatsuka. . . .

Even before the P-40 commander sighted the four Zeros, Nishizawa had picked

out the American planes, rocking his wings in signal to the other pilots and

pointing. Each Zero pilot nodded. Ota slid in just a few feet to fly off

Nishizawa's wing; Takatsuka did the same with Sakai. From afar the Japanese

planes never appeared to move. The pilots gave no indication that they were

aware of the P-40s above them.

The heavy American planes plunged at high speed, each pilot ready to fire. At

the last second, just before that moment when the Zeros would be helpless, the

Japanese formation leaped out of the way. But instead of rolling away and

scattering, as the P-40 pilots expected them to do, the Zeros nosed upward in a

swift, almost vertical climb.

The lead American fighter broke to the right and pulled up steeply into the

beginning of a loop. Still in the climbing turn, the airplane shuddered as it

ran into a stream of cannon shells. A wing tore off in the high-g maneuver,

sending the fighter tumbling crazily through the air. Score one for Saburo

Sakai.

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa hauled his Zero up almost into a stall, hanging on the

prop. A P-40 moved into his sights, and a long burst of two cannon and two machine

guns turned the fighter into a flaming streamer. The other two P-40s went down

before the guns of Toshio Ota, and Takatsuka.

The Zeros scattered now to the right and left, as the remaining six P-40s,

hovering overhead, raced to the scene—to find empty space before their guns. The

Zeros whirled upward, came around in wicked, tight loops, with P-40s in front of

their cannon. Nishizawa, Sakai, and Ota hammered a fighter apiece out of the

air; Takatsuka's quarry rolled and dived away.

Regrouping, the Zero pilots climbed and flew back toward Lae. It was quite a

fight: seven out of ten P-40s shot down, without a bullet hole in any of the

Japanese fighters. But how could the P-40 pilots have known what they were

running into.

The date of the air battle was May 7, 1942, and the four Japanese pilots had

made what they called a "dream sweep," on a reconnaissance mission from

Lae to

Port Moresby. When they took-off from Lae, their combined kills already were

great enough to command attention of all Japan. Saburo Sakai, with combat in

China, the Philippines, Java, and Lae, had scored 22 kills to become the leading

ace of Japan. Nishizawa, with barely a month in combat against the American and

Australian planes at Moresby, had chalked up 13 kills. Ota had scored 11;

Takatsuka trailed with nine.

Saburo Sakai went on to become Japan's greatest living ace with an officially

credited total of 64 kills in aerial combat. But it was Hiroyoshi Nishizawa who

was to be honored as the greatest Japanese fighter pilot of all time, the only

Japanese ever to reach the astounding figure of more than 100 kills (unofficial

count 102) in aerial combat.

Petty Officer Nishizawa received his baptism in combat as a pilot of the Lae

Wing. Only the most gifted and promising Navy fighter pilots were assigned to

this wing. It operated originally from Formosa to the Philippines, and

spearheaded the air battles that broke the back of Allied resistance in Java.

In April of 1942, Naval Captain Masahisa Saito led a group of Zero fighters

to a newly established air base at Lae, on the eastern coast of New Guinea,

where the designation Lae Wing became official. Lae-based Zero fighters flew

escort for twin-engined bombers staging out of Rabaul. During their stay at

their lonely airbase they got more than enough attention from American bombers

flying from Port Moresby's complex of airdromes only 180 miles away.

Some of the wildest air fighting of the Pacific War took place within this

area, a stretch of combat that had strangely evaded the attention of the

historians. The two types of American fighters based at Moresby were the P-39

Airacobra and P-40 Tomahawk and Kittyhawk models, airplanes the Japanese pilots

disdained as being greatly inferior to the agile Zero.

Lae was a miserable, wretched mudhole. It had a single dirt runway just 3,000

feet in length. Originally hacked out of the New Guinea jungle by the

Australians, the strip was served by a small seaport, the only feature of which

was a small Australian freighter, gutted and battered, lying around in the

harbor bottom.

On three sides of the runway towered the rugged mountains of the Papuan

Peninsula. The strip ran at a right angle from the mountain slope almost down

to the water. By the beach was a small aircraft hangar, riddled with bullets and

bomb fragments, and filled with the wreckage of three old Australian planes.

The Japanese operated the Lae airstrip much as their soldiers operated in the

field—severe austerity. There were no hangars, no maintenance shops, not even a

control tower. The men, pilots and members of the ground crews, slept in crude

shacks hastily thrown together from trees cut down at the edge of the field.

Ground motorized transport consisted of an ancient, captured American

automobile, which several mechanics had managed to rebuild into working

condition. The entire combat garrison consisted of 200 sailors who manned the

flak guns and maintained a perimeter guard at the edge of the jungle. One

hundred maintenance men, 30 pilots, and a half-dozen staff people completed the

roster. A comparable American installation would probably have had more than

3,000 men.

The daily routine varied only according to the dictates of weather or

American bombs. Each morning, at 2:30 a.m., the maintenance crews started to

work on the fighters. One hour later the pilots were awakened. After breakfast,

six of them went to the airstrip where they stood by six Zero fighters, warmed

up and ready for take-off, guns loaded and hot. These comprised the interceptor

defense of Lae. There was no radar, there were no patrols, but the Zeros could

be—and often were—rolling in seconds.

Even the combat routes became standard. To reach the Port Moresby area—a

prime target of Japanese bombers with its airfield and shipping facilities—the

Zeros and bombers had to cross the Owen Stanley Range which reached to 15,000

feet. Over the ridgeline, water lay before them, and then Port Moresby.

By April 11th, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa had already chalked up a confirmed total

of ten American fighter planes shot down in combat. On this day he added to his

total. Nine Zeros, making a fighter sweep to Moresby, caught four Airacobra

pilots unawares, and came out of the sun as a broad, sweeping scythe. The

brilliant ace Saburo Sakai, leading the formation, shot down two of the P-39s.

Nishizawa blew the wing off another to reach 11 kills, and Toshio Ota scored the

fourth kill of the day. The battle, beginning as it did with a dive out of the

sun, ended in just about five seconds

Nishizawa in the spring of 1942 was 23 years old. His record and performance

in combat proved so impressive that Saburo Sakai, then Japan's greatest ace,

personally selected him, along with Toshio Ota, to fly as a team. As the leading

aces of the Lae Wing, they became famous in the Japanese Navy as the "cleanup

trio."

"Hiroyoshi Nishizawa did not simply fly his airplane," Sakai explained to me

after the war, "he became a part of the Zero, welded into the fibre of the

fighter, an automaton which functioned, it seemed, like a machine capable of

intelligent thought. He was the greatest of all Japanese fighters.

"He was devoted to his life as a fighter pilot. You must understand this to

understand the man—everything else was subordinated to this role."

The man who was to become the Ace of Aces of Japan simply did not look his

part. Indeed, Nishizawa appeared to be in need of a hospital bed. He was five

feet eight inches, but his weight of only 140 pounds gave him a gaunt look. He

was prone to tropical skin diseases and terrible attacks of malaria.

But no matter how Nishizawa may have appeared on the ground, in the air he

was magnificent. His wingmen worshiped him. Strangely, Nishizawa remained aloof

from friendship. Only Sakai and Ota could, on rare occasion, penetrate his cold,

seemingly unfriendly, reserve. Often Nishizawa would pass an entire day without

any more conversation than was necessary to respond to a query or an order from

a superior officer. He would not meet the overtures of even his closest friends,

the men with whom he lived and fought.

Leading ace of the Imperial's crack Lae Wing,

he made the Pacific his private battleground and any

Allied plane that flew across it his personal target.

He was a "loner," disdaining friendship, silent, almost like a pensive

outcast rather than an object of veneration.

Nishizawa lived for only two things: to fly and to fight. Once he took wing,

he underwent a startling transformation. His reserve, his aloofness vanished. To

the pilots of the Lae Wing he became the "Devil."

He was totally unpredictable in the air, and no other pilot could do with the

Zero what Nishizawa would command, and receive, from his agile fighter. His

aerobatics were at once breathtaking, brilliant, impossible, and heart-stirring

to witness.

His eyesight was phenomenal. He could spot planes off in the distance long

before they were sighted by the other pilots, and this is an invaluable aid in

battle. Throughout his career, Nishizawa was never caught unawares by the enemy.

In the last two weeks of April 1942, Nishizawa, already an ace several times

over, ran into the doldrums. In this period, strangely enough, both Nishizawa

and Sakai failed to score a kill, despite several major air battles. If moody

before, Nishizawa was now positively black with anger.

On April 29th, in response to a blistering assault by American twin-engine

bombers against the Lae airdrome, six fighter pilots, including Nishizawa and

Sakai, went out for a surprise strafing attack against the Moresby airdrome.

To forestall the American anti-aircraft fire, the Zeros cleared the mountain

ridge at 16,000 feet, barely a thousand feet over the top of the Owen Stanley

Range. Then, instead of continuing at altitude, they passed the crest and pushed

over into steep dives.

Forming a triangle they plummeted toward the unsuspecting base, hitting the

field in a wide, howling sweep at treetop level. Fighters and bombers had just

been fueled and bombed in preparation for a mission. On their initial pass,

catching the Americans completely by surprise, the Zeros flamed three fighters

and a bomber, made three more strafing runs, and then beat it for home. Without

any opposition in the air there were no kills scored. The success of the

strafing runs failed to placate Nishizawa, and in his black mood he was

completely ignored by his fellow pilots.

On the succeeding mission, nine Zeros flew a sweep to Moresby for another

strafing run. But not today—nine P-39s and P-40s on patrol were waiting for the

Japanese, ready for battle.

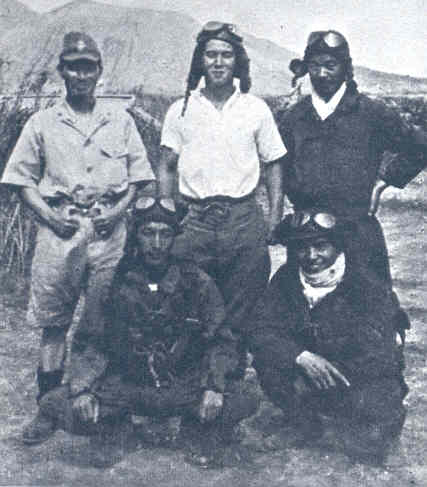

Nishizawa (front row, right) shown with

other members of the famed Lae Wing

(photo and caption from p. 38 of story)

The American fighters broke out of a circle and roared head-on at the Zeros.

In the wild scramble that followed, Saburo Sakai was the only Japanese pilot who

scored, with three kills that boosted his total well ahead of his fellow aces.

Two Zeros went down, but it was a fight that favored the Japanese. Despite

several occasions when he hammered away at the rugged American fighters,

Nishizawa returned to Lae "empty-handed." That night he refused to eat.

The next morning, May 2nd, the Zeros went back. The eight Japanese fighters

encountered thirteen patrolling American planes, but had the extraordinary good

fortune to close the distance between the two forces without being sighted.

First to spot the enemy ships, Nishizawa rocked his wings in signal; abruptly

smoke burst from his exhausts as he advanced his throttle to overboost power and

broke from the Zero formation. The others followed his lead as he swung around

in a wide turn, coming up to the American formation from the left and rear,

still without being seen!

Before the American pilots ever knew the Zeros were in the air, the Japanese

hit them like an avalanche.

Nishizawa screamed in, swift and turning. On his initial pass he led slightly

a trailing P-40; his cannon shells exploded the fighter's tanks. Immediately the

American planes scattered, but the evasion was too late. Nishizawa locked onto

the tail of a P-39; the American flipped on his back and dived at full power.

Anticipating the maneuver, the Japanese ace rammed the stick forward, raking the

Airacobra as the airplane flashed before the Zero's guns.

The battle had in these few seconds become a wild, swirling melee. Even as

Nishizawa's cannon scored his second kill, a P-40 locked on his own tail.

Against the Zero, there is simply no opportunity for maneuvering. Nishizawa hit

the throttle and hauled the stick back in a swift motion. The Zero flicked up

and around in an unbelievably tight loop. The Japanese pilot came out of his arc

on the tail of the P-40, pouring bullets and cannon balls into the cockpit.

That made three, and it was an exultant Nishizawa who flew back in a happy

ratrace with the other Zero pilots to Lae. Sakai scored two kills and the other

pilots shot down three fighters between them. It was a rout: hit without

warning, trying to maneuver after the Japanese had bounced them, the Americans

failed to down a Zero.

By the third week in May, Nishizawa's toll had climbed to 20 kills, making

him an ace four times over. Ever trying to dream up some new idea that would

foster continued dogfights, Nishizawa planned a special "dance" he wanted to

perform over the Allied field at Moresby. He drew Sakai and Ota aside one night

at the field and explained his plan. The next morning was scheduled for an

escort mission to Moresby. After the attack, the three pilots would "slip back"

to the enemy base and "do a few demonstration loops right over the field." The

usually dour Japanese ace chuckled: "it will drive them crazy on the ground."

Sakai and Ota stared in disbelief at Nishizawa—he actually seemed happy.

Led by commander Tadashi Nakajima, a force of 18 Zero fighters escorted a

heavy force of bombers in a major strike at the Allied installations. The raid

proved, however, a dismal failure. With ample warning of the strike, the

Americans and Australians dispersed their bombers, and the attack did little

more than dig holes in the runways.

In the air the story was different. Three American fighter formations pounded

in a rush at the Zeros. The Japanese planes turned to meet their adversaries

head-on. The clashing forces exploded into widely scattered individual

dogfights, exactly what the Zero pilots wanted. Nishizawa got one, to bring his

score to 21. Sakai, always pushing, always methodical, flamed two American

fighters to reach a tally of 29 kills. They were the only Japanese pilots to

score. Two Zeros went down.

After the battle, escorting the bombers on their return to Rabaul, Sakai

indicated by hand signals to Nakajima that he was going after some enemy planes

far below the Japanese formation. Nishizawa and Ota dove away with him. The

three reformed at 12,000 feet and returned to Moresby.

They found empty skies. Sakai slid back his canopy, motioning closer the

other two planes until the three Zeros were wingtip to wingtip. He raised his

hand over his head, described a ring with his thumb and forefinger, and then

raised three fingers. Both pilots waved in acknowledgement: three loops, all

tied together.

Sakai nosed down, Nishizawa and Ota flying as though the three airplanes were

one. Picking up speed, he eased back on the stick. The three Zeros went up and

over on their backs, soaring around in a precision loop. Twice more the fighters

went up, around, and down—and no enemy fighters, no flak!

Nishizawa rocked his wings, pointing down. He wanted to do the loops again,

this time starting the maneuver at six thousand feet. Down went the three

fighters, and three more times they whirled through the loops. There was still

no response from the base. The three disappointed Japanese headed home.

Just after nine o'clock that night an American bomber flashed low over Lae.

Caught by surprise, the Japanese were stunned when the bomber raced away without

dropping bombs or firing its guns. But a white object had plummeted from the

airplane, falling to the ground directly in the center of the runway. It was a

message container knotted inside a towel.

The message read: "To the Lae Commander: We were much impressed with those

three pilots who visited us today, and we all liked the loops they flew over our

field. It was quite an exhibition. We would appreciate it if these same pilots

returned here once again, each wearing a green muffler around his neck. We're

sorry we couldn't give them better attention on their last trip, but we will see

to it that the next time they receive an all-out welcome from us."

It was signed by a group of fighter pilots at Moresby. Nishizawa, Sakai and

Ota laughed long into the night . . .

More and more, the Americans smashed at the Lae airstrip with B-25 and B-26

bombers, and Japanese pilots began to score a mounting toll of the twin-engined

raiders. May 24th went into the record books of the Lae Wing as a "slaughter."

Eleven Zeros got into the air fast enough during an attack to hit six B-25s

which had come in on the deck. Nishizawa and Ota each flamed a bomber. Off

Salamanua, the remaining pilots shot down three of the remaining four bombers.

On August 2nd, Nishizawa made his first kill of a four-engined B-17 bomber,

an airplane that had frustrated his many other previous attacks, and which was

considered at that time to be the most dangerous American warplane in the skies.

The break for Nishizawa came over Buna at 12,000 feet.

Flying in a formation in which every Japanese pilot was an ace, he came in

against his target in a gradual, closing climb, rolling steadily as he poured

cannon shells into the fuel tanks. A splash of flame showed. Within seconds the

entire wing of the B-17 was ablaze, sending flames into the fuselage and the

bomb bay. The explosion that followed flipped the Zero through the air as if it

were a toy.

In the continuing battle, three Airacobras responded to radioed calls for

help from the B-17s. One American fighter came down in a screaming, full-power

dive, pouring cannon shells into a Zero which vanished in a ball of flame. As

the P-39 came around after a long pullout, Nishizawa rolled into him, his

shells entering the cockpit and killing the pilot. Sakai and Ota each scored a

kill to down the remaining Airacobras, but not before one of the American pilots

blasted Sueyoshi, Nishizawa's wingman, out of the air.

The Japanese ace fell into a bitter mood of self-accusation, blaming himself

for Sueyoshi's death. For several days he snapped at anyone who spoke to him.

But then, a week later, came electrifying news. Guadalcanal had been invaded by

the Americans. The Lae Zeros were to be sent out against the invasion force.

On August 7th, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa was officially credited with the shooting

down in the air of six American Navy F4F fighter planes, to go into the history

books of Japan as one of the handful of Japanese pilots ever to accomplish so

tremendous a feat. This toll was second, throughout the entire war, only to the

ace Kenji Okabe. In 1943, Okabe, over Rabaul, set the all-time record of seven

kills—F4F Wildcats, TBF Avengers, and SBD Dauntlesses. But Okabe took off and

landed three times during the day to fly three separate interception missions.

Nishizawa's six air kills were made after a long fight, against fighters, in a

long and sustained air battle.

The only other Japanese pilot of the Lae Wing to score that day was Sakai,

who was officially credited with shooting down an F4F and an SBD, and two TBFs.

(Official U.S. Navy records reveal that two TBFs were badly damaged during a

fight with a single Zero, but after sustaining and extinguishing fires, made it

back to their carriers. The claims were made not by Sakai, who was terribly

wounded in the fight, but by his wingmen.)

The battle over Guadalcanal was the beginning of the end for the famed pilots

of the Lae Wing. Saburo Sakai returned to the field with bullet fragments

imbedded in his brain, and blind in one eye. He was ordered back to Japan for

surgery. Within a few days, most of the Zero force was transferred to Rabaul.

From here, Nishizawa, now the leading ace on combat duty, led mission after

mission against American Navy and Army air units in the Solomons.

In November of 1942, with 52 kills to his credit officially, Nishizawa was

ordered back to the home islands. Here he had the opportunity to visit with

Sakai, recuperating from his operations. Nishizawa's toll in the air placed him

close to, but not yet exceeding, Sakai's own performance in the skies. But now,

blinded in one eye and out of the fighting, there was no question that Sakai

would eventually relinquish his position as the leading Japanese ace to

Nishizawa.

Or so it seemed. But Nishizawa had been assigned to the Yokosuka Training

Wing as a pilot-instructor. He chafed at the bit, and begged reassignment to the

Philippines. The day before leaving, during his visit to Sakai, he was forced to

tell his friend that almost all the great pilots of Lae—Ota, Sasai, Yonekawa,

Hatori, and the others—had been lost in battle. Of the original group of 80 Zero

pilots, only nine, including Sakai and Nishizawa, were still alive.

On October 25th, 1944, the Japanese Navy flew the first officially ordered

kamikaze attack of the war against the American fleet near Suluan in the

Philippines. Five Zero fighters flew as the "suicide" airplanes, each carrying a

single 550-pound bomb, and escorted by four Zero fighters flying as escort,

commanded by Hiroyoshi Nishizawa. The great Japanese ace, now with an accredited

total of more than 100 air kills in combat, led the fighters through skies

swarming with American planes that far surpassed the older Zeros in speed and

performance. Nishizawa took the kamikazes through and around storms. Following

his orders to the letter, he circled and watched the five suicide pilots push

over into dives from which they would never pull out. Then he returned with his

flight to the Zero base at Mabalacat on Cebu [1].

That night he volunteered to lead the kamikaze mission on the following

morning. Commander Tadashi Nakajima, who had been his superior officer at Lae,

refused permission.

"He told me," explained Nakajima shortly after the war, "that he was

convinced that he would soon die. He insisted that he had a premonition of

death. He felt that he would live no longer than a few days more.

"I wouldn't let him go. A pilot of such brilliance was of more value to his

country behind the controls of a fighter plane than he would be diving into an

enemy carrier, as he begged to be permitted to do. Nishizawa was an inspiration

to every Japanese pilot."

Even as the kamikazes began swelling to a terrifying torrent of death and

destruction against the American fleet, a new shipment of Zero fighters arrived

at Clark Field. Nishizawa was ordered to fly several other fighter pilots in a

transport plane to Clark, from where they would ferry the Zeros back to

Mabalacat [2]. Before leaving the base, Nishizawa watched in silence as the ground

crew wired a 550-pound bomb to his own fighter, which was flown on a kamikaze

mission by Naval Air Pilot 1st Class Tomisaku Katsumata (who dove successfully

into a deckload of armed and fueled American planes on the deck of a carrier off

Surigao).

Early on the morning of October 26th, 1944, Nishizawa was at the controls of

the old and unarmed transport that took off from Mabalacat for Clark Field.

Somewhere over the jungles of Cebu [3], skimming the treetops to avoid patrolling

American Navy fighters, the lumbering Japanese transport was spotted by a group

of Hellcats. The swift Grummans dove out of the sky, streaking after their

quarry.

There was never any doubt of the outcome. For several minutes, perhaps, the

consummate skill of Hiroyoshi Nishizawa staved off the inevitable. But there was

nothing, really, that he could do. The streamers of tracer bullets from the

Hellcats bracketed the old transport with their flashing lines. Bullets tore

into the bodies of the pilots in the cabin, smashed into the engines,

pounded the wings, slashed open the fuel tanks with fingers of fire. Twisting,

dodging, skidding and slipping wildly, Nishizawa at least made the enemy fighter

pilots marvel at their quarry.

And then it was over. A mushrooming ball of flame speared through the trees,

leaped upward from the jungle as the Hellcats arced around in climbing turns.

No one among them would ever know if he was the man to send to his death the

brilliant Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, Ace of Aces of the Imperial Navy of Japan, victor

over more than one hundred American aircraft shot down in battle.

Notes

1. Mabalacat is located on Luzon Island, not Cebu

Island. Cebu is far to the south of Mabalacat.

2. This makes no sense, because Clark Air Field

is next to Mabalacat.

3. Both Clark and Mabalacat are next to each other

on Luzon Island, and Cebu Island is far to the south. Therefore, it is not

possible for Nishizawa to have been over the jungles of Cebu on an extremely

short flight between Clark and Mabalacat. Several Japanese sources clarify that

Nishizawa was flying from Cebu Air Base to Mabalacat Air Base and was shot down

over Mindoro Island, which makes sense geographically. Inoguchi (1958, 61)

explains that Nishizawa was flying from Cebu Air Base to Clark Field when he was

shot down in the transport plane in which he was a passenger, not the pilot.

Source Cited

Inoguchi, Rikihei, and Tadashi Nakajima, with Roger Pineau.

1958. The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II.

Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

|