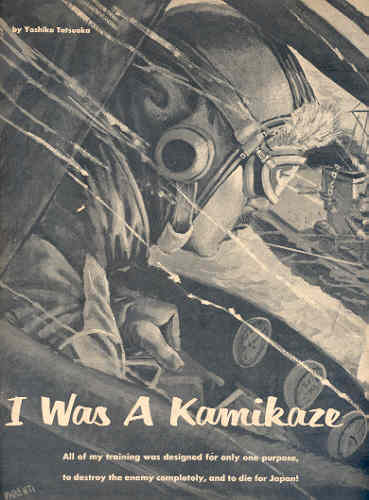

I Was A Kamikaze

by Yoshiko Tatsuoka

War Story, July 1957, pp. 54-9

Introductory Comments

"I Was A Kamikaze" is about a Japanese fighter pilot

who trains for a kamikaze mission but never goes on one before the war's end.

This story is clearly fictional despite the magazine War Story's presenting

it as being true. Inexplicably, the pilot's given name of Yoshiko is a Japanese

female name.

Tatsuoka's account has a few similarities with the book

Kamikaze (1957) by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon T. Allred, who also wrote a

much shorter version as the story entitled "I Was a Kamikaze Pilot" in the

January 1957 issue of the men's adventure magazine Cavalier. For example,

like Kuwahara, Tatsuoka has basic training and gets assigned to a kamikaze unit

at the non-existent Army air base at Hiro in Hiroshima Prefecture. Tatsuoka

almost becomes an ace by supposedly shooting down four enemy planes as part of

an invented fighter squadron in the Philippines.

Various details in "I Was A Kamikaze" do not correspond

to historical details of wartime service by real kamikaze pilots (e.g., Army

pilot would not be trained in Navy Zero fighter). Most likely this story was

written by an American writer who had picked up a few details from reading Yasuo

Kuwahara's fictional story of a kamikaze pilot and various other wartime

literature written in English. It is doubtful that the real author ever even visited

Japan.

The original article in War Story included four US Navy

photographs and one Japanese photograph of kamikaze pilots receiving their final

instructions before taking off on a suicide mission. The Navy photographs showed

kamikaze attack damage on USS Ticonderoga and USS Intrepid (see

below), an unsuccessful kamikaze plane crashing into the water, and a Japanese

bomber aiming for an aircraft carrier.

Notes have been added to the story in order to provide

comments on a few of the inaccuracies. Click on the note number to go to the

note at the bottom of the web page, and then click on the note number to return

to the same place in the story.

All of my training was designed for only one purpose, to destroy the enemy

completely, and to die for Japan!

Perhaps it is as they say, that I am one of the rarest of human beings–a

living former Kamikaze pilot [1].

There are not many of us, that is certain. We were trained

for only one purpose–to give our lives in suicide dives on enemy warships.

We were the flower of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces,

the last hope of our nation as it fought desperately to drive back the American

forces closing in around our beloved Home Islands.

I was not always a kamikaze pilot. For years I flew

conventional fighter aircraft. I shot down at least four American planes and

strafed and bombed countless American troops and ships and positions.

Neither I nor my comrades could change the final outcome

of the war. Nippon was doomed to defeat once the overwhelming force of United

States industrial production was thrown against it. We could not alter the

result, even though we stood ready to die for our country and for our Emperor.

The war is long over. Yet, my country is still rebuilding

its shattered cities and levelled factories. These were burned and blasted by

the vast fleets of American bombers that swept over Kyushu, Honshu and Hokkaido.

I am neither ashamed nor sorry that I was a Kamikaze

pilot. I no longer hate Americans, but I make apologies to no one for having

been faithful to the principles I learned as a boy and man. I do not regret that

I loved my country and was willing to fight for it with every ounce of strength.

"Only the best of Japanese men can enroll in the Army's

flying units," we were told when I was a boy of 16. It was true. When I told my

parents that I had decided to enlist for training, they bowed and hoped that I

would be able to meet the requirements and pass the examinations.

These were rigorous. I enlisted in the Imperial Air Force

in May of 1941. I was sent immediately as a trainee to Hiro Air Base [2], not far

from the ill-fated city of Hiroshima. There I underwent more tests and

examinations for nearly two months.

These were not of the sort familiar to Westerners. Our

officers and our honchos–sergeants–wanted to know far more than whether we were

physically fit and mentally alert. Their task was to determine and to prove

whether we were men and brave enough to be worthy of flying for the Emperor.

"Out josan–women!"

With this shouted insult, our drill masters would awaken

us at all hours of the night and early morning. When we heard the command, we

had to leap up from our thin pallets on which we lay, covered by only a thin

blanket.

Naked, we would run outside. There our leaders would be

waiting, ready to put us to some new and fiendishly devised test. One morning,

they would beat us with whips as we ran long gauntlets. At other times, they

would drench us with ice cold water pumped from hoses. On yet other occasions,

they would order us to run in circles until we dropped from sheer exhaustion.

Those among the cadets who flinched once were beaten

mercilessly. The second offense brought thirty days of solitary confinement

during which time the culprit received only a tiny bowl or rice and a thimbleful

of saki [3] each day.

The third time? Expulsion in disgrace!

"Those who are expelled are expected to redeem themselves

in the ageless tradition of the samurai," our officers told us. "They

will be permitted to commit hari-kiri [4]!"

Of the six men who were expelled, four expunged their bad

records by killing themselves and were restored to honor after their deaths. The

two who did not came from excellent families in Tokyo. Although their parents

were wealthy, they were disgraced by the cowardice of their sons. The men who

were not men were not permitted to return into their homes. They were forced to

seek work as sewer-coolies, the only employment open to them. Their names were

stricken from the rolls of the school.

There were simple words of praise for those of us who

completed the first phase of our training successfully. The Colonel, an Imperial

Baron, addressed us himself.

"You have begun," he declared. "It is only the beginning.

You have proven yourselves to be men worthy of serving the Emperor. Now you must

prove yourselves worthy and able to carve the destiny of Nippon from the flesh

of her enemies."

We shouted out banzais and felt the fierce flush of

pride. I was given a short leave and returned to my home in Sapporo. My father's

welcome was an even greater honor.

"You are a man, my son," he said with great dignity. He

bowed his head to me–to me! In Japan, a father can pay his son no greater

compliment! My heart was ready to burst with joy. When my mother and sisters

knelt before me, and then honored me with the tea ceremonial, I felt as though

my life could never be more full or complete.

I returned to my base to begin my actual flying training.

This proved to be even more rigorous and gruelling than what had gone before.

We attended endless classes, learning the theories of

flight, navigation, radio communications. We were toughened and honed to a fine

edge physically.

One day, we were given our first flight–as observers in

two-seat Mitsubishi trainers. I thrilled at the experience and found that flying

was more than just an occupation–it was the greatest of emotional experiences.

It was November. Our training schedule was stepped up,

intensified. We could not understand why. There was an air of urgency behind

everything our officers did or told us.

We understood everything on December 6 [5]–December 7 in

America. Our heroic pilots and sailors had attacked Pearl Harbor and the enemy

strongholds in the Pacific.

"Japan is at War! Banzai!"

The entire force at our air station heard the news at a

special parade. We shouted our lungs out and saluted the flag and the Emperor.

By February, I had soloed. My instructors decided my

reflexes and natural abilities suited me to be a fighter pilot. I was given four

months of further advanced training in the fast, highly maneuverable Zeros [6] that

wreaked such havoc with the Allied air forces in the early years of the war.

I chafed and fumed and begged for transfer when I was

assigned to duty as an instructor after completion of my training.

"You are a second lieutenant, Yoshiko," my commander

informed me coldly. "You will obey the orders of your superiors."

For two and a half long, miserable years I taught others

to fly and to fight and then watched them go off to the fronts. I was promoted,

but it was little compensation for my failure to fight and win glory.

It was not until October, 1944, that my orders

transferring me to a combat unit arrived. I was commanded to leave my station at

Haneda Air base [7] and report to the commandant of the replacement depot at

Yokohama. Before I went, I was to receive ten days' leave.

My comrades and I celebrated that night. We drank

countless flasks of saki and amused ourselves with the geishas. My

father greeted me when I arrived home. He insisted on taking me around to all of

my friends. I was toasted and was the center of attraction.

I was sent to the Philippines, where I joined the 123rd

Fighter Squadron [8]. America's might was beginning to make itself known. Admiral

Halsey's carrier task forces were striking at the islands.

I began flying immediately. Now, all the days and months

of training–and the years of waiting–were worthwhile. I was amazed to find that

the Americans had such excellent aircraft and were able to fly so well. We had

been told their ships were poor and their pilots untrained and inferior.

It was not until my eighth combat patrol that I was able

to bag my first enemy aircraft. It was a Marine Corps F4U Corsair. The pilot had

broken off from his companions. He was diving to strafe some of our shore

positions below.

I requested permission from my flight commander to go

after the Corsair. Permission was granted and I, too, went into a steep dive.

The kill was disappointing, in a way. The enemy pilot was

not aware of my presence. He continued his dive completely oblivious to the

danger that was shrieking down on him from above.

I waited until I had a perfect picture of the ship in my

ring sights. Then I pressed the trigger button. My light craft shuddered and

shook as the machine guns hammered. Streams of tracer bullets streaked from the

wings.

It was all over in moments–much faster than I had thought

or hoped it would be. The fingers of hot lead stabbed into the fuselage of the

Corsair, ate along the pilot's compartment and ripped into the engine cowling.

The American plane simply disintegrated. The tanks must

have blown up. I pulled out of my dive and looked down. There was no parachute .

. .

I was congratulated upon my return to the base–and my

first victory was chalked up beside my name. The other pilots stood rounds of

saki in the mess.

I had to wait another week before making another kill.

This one was not so easy. The plane was a B-24, a Liberator bomber. I found it

over the southern tip of Luzon. It was in trouble, one of its four engines had

been shot out by our ground defenses.

"I respectfully beg that I may be permitted to engage the

enemy alone," I asked the flight commander in the formal manner handed down from

the days of the Samurai.

"It is granted," came the reply over my radio. "Banzai!"

The bomber was crippled, its speed cut. However, its crew

was obviously unhurt. The multiple tail and belly and top turret guns spewed out

bullets that formed a wall through which I could not penetrate.

I banked and twisted and maneuvered, trying to find some

hole in the defensive screen. It was useless. Bullets nicked my wings and holed

my fuselage.

I knew that I could not permit my prey to escape without

dishonoring myself. Grimly, I pulled up and climbed above the B-24.

I was determined to crash into it as a last resort. I

pushed the stick forward and began to dive. The air speed indicator spun. I was

nearing top speed . . .

I saw the smoking tracers coming up at me. The distance

between us narrowed. I called my commander and told him what I intended to do.

There was no time to hear the answer. Suddenly the top

turret guns of the B-24 cut out. It was the opportunity I had sought. Like a

flash, I tripped the trigger. There was only a second in which to bring my guns

to bear and fire my guns. The slugs tore into the bomber. I pulled up at the

very last instant.

I looked back and saw the lumbering craft yawing into a spin. White parachute

blobs blossomed as the ship started to burn . . .

My third and fourth victories were both B-26 bombers [9].

I got them three days apart. I needed only one more to win my rating as an ace.

The opportunity never came.

The pressure of the American advance toward our homeland was increasing. The

peril to our country was growing greater by the day. Drastic measures had to be

taken . . .

For some time, special units of consecrated Japanese pilots had been flying

Kamikaze craft–small, fast planes loaded with

explosives which they dived or flew into American ships. The first Kamikaze

had gone gloriously to his ancestors in October, 1944. His gallant act had sunk

an enemy destroyer [10].

Now, the High Command ordered the suicide fleets expanded.

Thousands of the Kamikazes would be needed to protect the Home Islands from the

invasion many predicted would soon come.

The craft were called "Kamikazes"–"Divine

Wind"–after the Heaven-sent storm that destroyed Genghis Khan's invasion fleet

more than 700 years before [11].

I was sent back to Japan–to Hiro air base. I had been

chosen for the special duty because of my determination to crash the B-24. It

was a great honor. Those who died in Kamikaze attacks would receive

special prayers from the Emperor himself!

Our Squadron at Hiro–the Fifth [12]–was

newly equipped with Hayabusa II fighters, specially modified for use as

Kamikazes. They were fantastically fast and maneuverable craft. We trained

with them for weeks.

It was February, 1945.

The Americans were assaulting Iwo Jima–a barren island

less than 800 miles from Tokyo itself!

I volunteered to pilot ships on the missions assigned to

our squadron. I was refused.

"We must save our best pilots for the very last–when the

sacred soil of Japan itself is threatened," my colonel informed me. "You are one

of the best. You must wait until we are making our last-ditch stand and you are

truly needed."

It was a comfort. My pride was assuaged. Yet I envied the

heroic flyers who climbed into their craft and took the banzais of those of us

who remained behind. They flew off–toward Iwo Jima, their ships packed with high

explosives–never to return [13].

Their deaths brought everlasting honor to them, to their

families and to our squadron. They were the greatest heroes of all in the

history of Nippon–a history studded and spangled with accounts of the

unflinching courage of the nation's fighting men!

Iwo Jima was taken–but at terrible loss to the enemy. The

American assault force lost nearly 20,000 men in the 26 days that our soldiers

clung to the embattled island.

Hundreds of our suicide craft were employed. They sank or

damaged large numbers of enemy ships [14].

For a time, it looked as though the Kamikaze might turn the tide of the

war.

The hangar deck of the USS Intrepid shows the

marks of two successful Kamikaze attacks, on

November 25, 1944. Vessel was hit four times.

(caption from original article)

In April, the enemy began its invasion of Okinawa–another

step closer to Japan.

"Allow me to go," I pleaded with my superiors.

"No, not yet."

While the battle for Okinawa raged, hostile bombers came

over Hiro air base and rained bombs on it for hours. Our fighters, hoarded for

the final battle, were not permitted to go up to intercept them.

Most of the men who had been with the Fifth Kamikaze

Squadron when I reported for duty were gone. Only a few of us "old ones"

remained. Fresh replacements were brought in. Our squadron was shifted to

another base.

We were able to give the new men only a day or two of

familiarization training. Then they took off–part of the 1,900 who gave their

lives in suicide flights during the Okinawa Campaign [15].

Japan was short of gasoline. Our own refineries were blown

to bits. The sealanes used by tankers to bring fuel from the Asiatic mainland

were infested with enemy ships and submarines. We were forced to save every

airplane. The stranglehold the enemy had on Japan was tightening.

The fantastic effect of the Kamikaze attacks was

not made public by the Allies. We laughed with scorn when American Admiral

Halsey claimed the attacks were only 1 percent effective. We knew then for

certain that the Americans lied in their propaganda.

(Ed. Note: Actually, Tatsuoka has a point there. Strict

censorship was imposed on all mention of Kamikaze attacks. Postwar tabulations

showed that the weapons were deadly. More than 2,000 direct hits were scored on

American vessels by the suicide craft [16].

Such ships as the carriers "Franklin" and "Intrepid" and many others were

blasted by the Kamikazes.)

Okinawa was lost to us on June 21, 1945. It was a day of

official mourning. We knew now that the ultimate struggle for the very life of

our nation was near.

The swarms of B-29s saturated the Japanese islands with

explosive bombs and incendiaries. Tokyo, the beautiful capital, was

bomb-cratered and gutted. All our cities fared equally.

Hate the Americans? Of course I hated the Americans. I hated them and I

wished only to have the opportunity to repay them for their savage attacks on

our homes and our civilians.

I no longer hate them. I realize that they were fighting a war as best they

could. I also realize now that our own forces committed hideous atrocities and

levelled the cities of other nations. Even so, I cannot forget the sight of the

heaps of corpses–of men, women and children.

Then, it was different. I hated and I wanted to kill. Why?

More than a third of the Japanese city of Nagoya was destroyed by U.S.

bombing planes. Yokohama was 41 percent wiped out. More than half of Tokyo was

gone.

We girded ourselves for the final blow. The entire nation steeled itself for

what was to come and swore to fight to the death. It would have been difficult

for the Americans to invade the Japanese Home Islands. Every inch of ground

would have been defended with a ferocity that no Western mind can comprehend.

(Ed. Note: Official Pentagon estimates placed the number of American

casualties to be expected in the planned invasion of Japan in the neighborhood

of 1,000,000!)

Perhaps the price would have been too heavy for the Americans to pay. Perhaps

our determination would have won us at least a better peace. I don't know. I do

know that I and my comrades stood ready to die–willingly and

enthusiastically–for the defense of our homeland.

Our hoarded planes were ready in dispersed and underground

hangars. Our precious supplies of gasoline would have been enough for the

all-out defense of Nippon.

Every building, every street would have been a

battleground. We were sworn to die before we would surrender. There were strong

defenses on the beaches, in the hills. Pillboxes and bunkers had been built in

every town and in almost every field.

Daily, the last of us in the squadron formed and listened

for our orders, we were the best remaining. Each of us had his designated ship.

The planes were fully loaded and gassed. They needed only a flip of a switch and

a twirl of the propeller to fly against the invasion fleet,–perhaps, destroy it.

The opportunity to give our lives for our country never came. On August 6,

1945, the city of Hiroshima died in the awful fury of a hellish holocaust. More

than 80,000 of my countrymen died in that fearful moment when the first atomic

bomb to be used in war was dropped. Thousands more were to suffer and die slow,

agonizing, lingering deaths.

Three days later, another of the horrible weapons was used against Nagasaki .

. .

The entire squadron reported to the commandant in a body. We stood, with

tears running down our cheeks, begging him to allow us to take off. We wanted to

fly anywhere–anywhere at all where there were American ships.

"Whatever we destroy will mean that many fewer of the

devils and their hell-bombs," Capt. Nakigawa, our spokesman declared. "We–the

members of the squadron–wish this to be our fate, to die in a last blow . . ."

The commandant bowed his head. He said nothing, but handed

us a scrap of paper. On it were the kana ideographs telling of the

government's decision to surrender.

"Banzai! Long live the emperor!" our superior said

unevenly. "Farewell!" He turned and walked back to his office. We knew only too

well what he was about to do.

Orders absolutely prohibiting any flights against the

Americans were received minutes later from Tokyo. The commandant was spared

that. He was already dead. He had disembowelled himself.

There were many others who followed him in death. I

considered committing hari-kiri and gave up the idea only because I still

hoped to strike back, once the American occupation forces arrived.

"We will yet be able to hurt them," I told my comrades.

Many of them believed me. This was not to be. The war was over and the enemy

permitted the Emperor to remain on his throne. It was He who gave us orders to

remain calm and to help rebuild our shattered cities and broken homes . . .

Yes. The war is over a long time now. As one who fought

and saw the death and destruction of war, I can only pray to my ancestors there

will never be another.

Even so, I have no regrets for having been a flyer. I

fought–for my country, for my home. So did those who gave their lives in the

suicidal Kamikaze attacks. They may have fought for a wrong ideal–but it

was an ideal, the safety and supremacy of our nation.

Many men have died for this–rightly or wrongly.

To them all, regardless on which side they fought, I offer

a salute. I wish them peace in their warriors' graves. Their honor is secure,

forever . . .

Notes

1. Actually, thousands of Japanese Navy and Army

men who were assigned to special attack units and trained for suicide attacks

against enemy ships survived to the end of the war.

2. The Japanese Army did not have a base at Hiro

or any air base near Hiro. This reference appears to have come from the 1957

book Kamikaze by Yasuo Kuwahara and Gordon T. Allred.

3. The author misspells the common Japanese word

sake as saki, which would not happen if the author actually were

Japanese.

4. In the same way as Note 3, the author misspells

hara-kiri as hari-kiri.

5. At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack on

December 7 in Hawaii, it would have been December 8, not December 6, in Japan.

6. It makes no sense that Tatsuoka would have

advanced training in Navy Zero fighters, since he was in the Army according to a

paragraph earlier in the story.

7. Haneda was a civil airport, not an Army air

base, during WWII.

8. Japan did not have a 123rd Fighter Squadron

that fought in the Philippines.

9. It is not possible that Tatsuoka shot down B-26

bombers in the Philippines after October 1944, since the last combat mission of

a B-26 bomber in the Pacific Theater of Operations took place in January 1944.

B-26 bombers did not fight in Philippines.

10. A destroyer was not sunk by the first

kamikaze squadron on October 25, 1944, but the escort carrier USS St. Lo

(CVE-63) was sunk.

11. Khubilai Khan, not Genghis Khan, invaded

Japan and had his ships destroyed by a typhoon in 1281. This was less, not more,

than 700 years before this article was published.

12. The Fifth Kamikaze Squadron at Hiro Air Base

did not exist.

13. No such kamikaze squadron flew a mission

toward Iwo Jima from the fictional Hiro Air Base. Only the 2nd Mitate Unit of

the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps made such a suicide attack on ships near Iwo

Jima. This unit took off from Katori Air Base in Ibaraki Prefecture on February

21, 1945. The suicide attacks sunk the escort carrier Bismarck Sea

(CVE-95), heavily damaged the carrier Saratoga (CV-3) and cargo ship

Keokuk (AKN-4), and slightly damaged the escort carrier Lunga Point

(CVE-94) and amphibious ships LST-477 and LST-809. The 2nd Mitate Unit lost 43

men in attacks on that date (20 men in 10 Suisei bombers, 18 men in 6

Tenzan bombers, and 5 Zero pilots).

14. The statement that hundreds of Japanese

suicide craft sank or damaged large numbers of enemy ships during the Battle of

Iwo Jima is erroneous. As explained in Note 13, only the 2nd Mitate Unit carried

out a suicide attack on ships near Okinawa. On February 21, 1945, this suicide

unit lost 21 planes and sank or damaged 6 American ships.

15. More than 1,900 kamikaze airmen lost their

lives in suicide flights during the Okinawa Campaign. The total numbers vary

based on the source,

but Ozawa (1983, 78-9) analyzes various references and concludes that 2,955 Special

Attack Corps members lost their lives in suicide attacks during the Okinawa

Campaign (2,026 in Navy, 929 in Army not including 88 men lost in the Giretsu

Airborne Unit).

16. Kamikaze aircraft did not score more than

2,000 direct hits on American vessels. Figures vary with different sources, but

Yasunobu (1972, 171) puts the figure at 410 ships, which includes those damaged

by near hits by kamikaze aircraft. Rielly (2010, 324) states the figure is 407

ships damaged. Ozawa (1983, 88) has a table that compares the figures from

different Japanese sources.

Sources Cited

Kuwahara, Yasuo, and Gordon T. Allred. 1957. Kamikaze.

New York: Ballantine Books.

Ozawa, Ikurō. 1983. Tsurai shinjitsu: kyokō no tokkō shinwa

(Hard truths: Fictitious special attack myths). Tōkyō: Dohsei Publishing Co.

Rielly, Robin L. 2010. Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A

Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships, by Aircraft

and Other Means. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Yasunobu, Takeo. 1972.

Kamikaze tokkōtai (Kamikaze

special attack corps). Edited by Kengo Tominaga. Tōkyō: Akita Shoten.

|