The Navy Crew That Kidnaped 77 Kamikaze Harem Virgins

by Dean W. Ballenger

Art by Charles Copeland

Stag, September 1961, pp. 20-3, 42-4.

Introductory Comments

This fictional tale, set during the Battle of Okinawa,

describes the capture of an old Japanese tug by an American landing craft. The

Americans who board the ship are shocked to find 77 young Japanese women below

deck. Two crewmen get the enviable task of "guarding" these beautiful women

while their ship leaves to send back help to handle the prisoners of war.

Unfortunately, the two men get "rescued" after three weeks on a small island

near Okinawa where they became friendly with their supposed prisoners.

This type of outlandish account is typical of many

stories published in men's adventure magazines, which reached their peak of

popularity in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The stories are purported to be

true, but actually most of them have little or no historical basis. The

protagonists bravely face dangerous situations while often encountering

beautiful young women in their adventures. The historical backdrop for the

stories often includes actual locations and events. The magazine articles

typically have painted illustrations that depict part of the story, and they

frequently include stock photographs that are seemingly related to the story.

For example, "The Navy Crew That Kidnaped 77 Kamikaze Harem Virgins" has a stock

photo of two young women in kimonos who supposedly were recruited to entertain

kamikaze pilots on the eve of their deaths.

The author, Dean W. Ballenger, makes many mistakes with

Japanese names, such as using male names for the young Japanese women. The

story's historical background is by and large accurate, but some details are

incorrect. The island where the Japanese tug is captured in early June 1945

actually exists, but this island in the Kerama Islands had already been captured

by the Allies in late March 1945 as part of their preparation for the invasion

of Okinawa.

The story's premise of young women provided to kamikaze

pilots the night before their scheduled attacks is one of several kamikaze myths

that arose during WWII and the postwar period. The women in the story are

being shipped to Miyako Island, which had been subjected to steady bombardment

since late March 1945. The island actually did not have any kamikaze pilots

waiting for their final mission, although a few kamikaze pilots took off from

Miyako in late July after they flew to the island from their main base in

Taiwan.

Notes have been added to the story in order to provide

comments on a few inaccuracies. Click on the note number to go to the

note at the bottom of the web page, and then click on the note number to return

to the same place in the story.

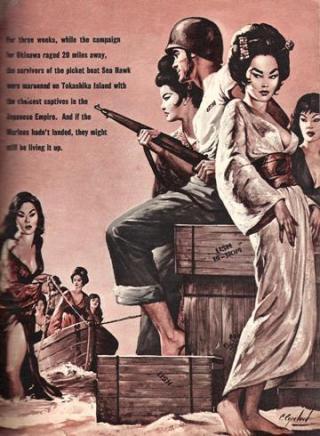

For three weeks, while the campaign for Okinawa raged 20 miles away, the

survivors of the picket boat Sea Hawk were marooned on Tokashika Island with the

choicest captives in the Japanese Empire. And if the Marines hadn't landed, they

might still be living it up.

The Riyuko Maru [1] was trapped. The

decrepit old Japanese tug was in a cove on Tokashika Island [2],

which is about 20 miles west of the southern tip of Okinawa. She could neither

escape to sea nor outshoot the LCI [3].

In four swiftly fired rounds the gunners of the LCI's three-inch rifle

demolished the tug's 37-mm gun and annihilated her crew. Then they lobbed HEs at

the tug's water line. Meanwhile other gunners swept her deck and bridge with

fire from the LCI's 40 mms, 20s and two 50-caliber machine guns.

Two minutes after the LCI opened fire a white fundoshi [4]

attached to a bamboo stick appeared above the debris of the Riyuko Maru's

bridge. At the same time the tug's sporadic rifle fire was terminated.

"Cease fire!" Lieutenant Commander Kenneth S. Madsen, the LCI's young

captain, bellowed to his men.

The tug was sinking. Soon her keel was on the cove's coral floor. But because

the cove was shallow the tug's deck remained about 30 inches above the water. "I

can't figure why she didn't blow up," Madsen said to his executive officer,

Lieutenant Warren I. Leigh. He

had been certain that the Riyuko Maru was an explosives-laden kamikaze

ship.

The fundoshi began to wave furiously. "It's a trick of some kind," Leigh

muttered. "I never heard of a Jap surrendering his ship."

"He's trying to lure us closer, " Madsen replied., "so he can be sure he'll

sink us when he blows up his ship."

Warily, the Americans watched the tug. An interminable time later the

fundoshi-waver peered over the debris of the bridge. "Nail him!" Madsen shouted

to his 50-caliber gun crews. "Delay that!" he bellowed an instant later. He had

looked through his binoculars. "That Jap's an old man," he said incredulously.

"He's no Nip naval officer." He gave the binoculars to Leigh.

77 Kamikaze Harem Virgins

Leigh put them to his eyes. "The Japs must have found him in their old

sailors' home, " he said after he focused on the fundoshi waver. "He acts like

he really wants to surrender."

Madsen looked again, "He seems anxious, all right," he agreed. "But . . ." he

added tight-lipped, ". . . you can't trust a Jap."

Ten uncertain minutes elapsed. The old Japanese was standing now. He

continued to wave the fundoshi. Then he gesticulated to someone behind the

debris. Immediately this unseen Japanese threw an Airsaki [5]

rifle into the sea. Then two more.

Several minutes later Madsen said, "I'm going to board his ship . . . in the

whaleboat. If I make it I'll bring him back—and the other

survivors. We can transfer them to the first DD that comes along. Maybe they'll

be able to come up with something that CinCPac ought to know."

CinCPac, he realized grimly, needed all the information it

could obtain about the Japanese. The Okinawan campaign, already far beyond its

scheduled conclusion, was unparalleled in scope and ferocity. Victory was

nowhere in sight.

Madsen asked for volunteers to accompany him in the

whaleboat. Among these men were Boatswain's Mate First Class Donald S. Wilkes of

Hinds County, Mississippi, and Gunner's Mate Second Class Ray D. "Guns" Gartner

of Kansas City, Kansas.

Soon the Americans were aboard the Riyuko Maru.

They stared in amazement. Her captain, who had waved the fundoshi, looked like

an Oriental elf. He was bearded. He was less than five feet tall and he could

not have weighed 100 pounds. He was 72-year-old Ikeda Tamashiro [6],

a professional tugboat skipper. The survivors of his crew were pre draft-age

boys. The tug's armament had consisted of one battered 37 mm field rifle, two

.257 caliber machine guns—one of which immediately jammed—and several Arisaki

rifles. The Japanese hadn't had enough ammunition to put up an effective fight,

even if they had known how to operate their pathetic weapons.

"I make fights because I scared," Captain Tamashiro said

in understandable English. "When hopeless, I surrender. Very useless for these

boys to die. Also the girls."

"What girls?" Commander Madsen demanded.

Captain Tamashiro indicated the forward hatch. "They

below," he said.

The American strode toward the hatch. Madsen jerked it

open. Then he and the others incredulously at the moon-faced young Japanese

girls who looked up at them. They were attired in identical purple kimonos,

encircled by white silk sashes. Each girl's hair-do was sustained by a white

ribbon.

Madsen closed the hatch. Things happen to me, he reflected

dejectedly, that don't happen to other officers. He looked at the little

Japanese. "What are you doing," he muttered, "in a combat zone with a boat full

of women?"

The Riyuko Maru was transporting 77 virgins to

Miyako island [7], Captain Tomashiro explained. They

would give solace to kamikazi pilots the night before these airmen died in

flaming crashes on U.S. Navy warships. So few ships remained of the Imperial

Navy that none could be diverted for this mission, Tamashiro added. So he and

his boat—a 1400-ton deep sea tug which had done salvage operations in the Sea of

Japan—had been conscripted. The Riyuko Maru was armed with barely-usable

weapons which the Imperial Army had cast aside. Then 17 boys, the sons of

fishermen in the Wakasa Bay area, were recruited for the crew.

"Very regrettable," Tamashiro said in the depressed tone

of a man whom fate has often bludgeoned. "Eight of boys killed . . . I should

have made surrender without fights." His little black eyes glinted. "War was

idea of ambitious ones," he said bitterly. "Not good for Japanese people."

But Madsen wasn't listening. He was looking at the bodies

of the dead Japanese. Then he looked at the hatch which contained 77 virgins.

His brow was furrowed. But he was a man of swift and competent decisions and he

said to his men, "We'll take Tamashiro and his crew with us. And the bodies . .

. we'll bury them at sea."

His eyes focused on Guns Gartner and Don Wilkes. "You

men," he said, "will remain here and guard the women, who are now prisoners of

war. We'll send someone for you just as quickly as possible."

An hour later Gartner and Wilkes watched the LCI wallow

out of the cove. They were uneasy and apprehensive. Male POWs could be

disciplined by a few slugs from their M1s—but what if the women charged out of

the hold?

The unique circumstances of these two young Navy men was a

capricious consequence of the invasion of Okinawa, a campaign which began on

Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, after a naval armada of 1321 ships had transported

183,000 assault troops to the island. Commander Madsen's LCI—named by her crew

the "Sea Hawk [8]," a strange, lilting name for a

plodding landing craft—had been one of these troop carriers.

The campaign was to be a "quickie," lasting less than a

month. U.S. intelligence had estimated that the Japanese had 58,000 troops on

Okinawa and only 187 major artillery pieces.

But this was one of the most inaccurate intelligence

reports upon which a major U.S. campaign has ever been based. Okinawa was

defended by the flower of the Imperial Army, the 115,000-man 32nd. The 32nd was

commanded by Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, a brilliant strategist.

It was immediately evident that the Japanese were

determined to hold Okinawa and that they would depend principally upon suicidal

kamikaze fliers.

By April 3, the sheltered anchorages which had seemed so

safe were clotted with damaged U.S. ships. But the kamikaze attacks had just

begun. Further, U.S. fighters and bombers could not effectively reduce them;

they were well dispersed and camouflaged. The Navy's system of reading the

Japanese code was of no help; the kamikaze attacks were launched by local

commands without prior communication with the Supreme War Council in Tokyo.

On April 12, the day of Roosevelt's death, thinking that

the Americans would be too demoralized to resist, the Japanese decided to try to

destroy the invaders with kamikaze attacks of unprecedented scope and savagery [9].

They hurled 175 HE and incendiary-laden planes in 17 separate raids against

units of the Fifth Fleet. Many small ships were sunk and several major units,

including the battleships Tennessee, Idaho and New Mexico [10],

were grievously damaged. More than 2000 Navy men were killed [11].

With this attack, remaining hope of a quick U.S. victory

vanished. The campaign, the invaders realized bitterly, would be long and

costly. Appalled by his losses and fearful of the future, Admiral Spruance,

commanding the Fifth Fleet, radioed Admiral Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific:

"The skill and effectiveness of the enemy's suicide air attacks and the rate of

our loss and damage are such that a means should be employed to reduce further

attacks. Recommend a picket line. . . ."

Subsequently CinCPac decided to set up a radar picket line

in a circle 50 miles out from Okinawa. These ships would warn the major units of

the approach of kamikazes. The cunning suicide pilots had been making their

attack runs barely above the waves, a tactic which made the Americans' radar

practically useless since schools of flying fish and low-gliding sea birds

caused the same blips on radar screens. As a consequence, the kamikazes

frequently approached so close to a victim before they were discovered that AA

guns could not be depressed enough to fire at them. And sometimes they crashed

into a ship even before her general quarters alarm could be sounded.

Mine sweepers, destroyers, LCIs, LSTs and several VP class

patrol boats were hurriedly armed with additional AA weapons and ordered to form

the picket line. They were given the code designation "Small Boy."

Immediately the Japanese, frustrated and enraged by the

Small Boys, tried to destroy them. U.S. losses in ships and men were dismaying.

In desperation, the picket line was double banked.

But the wily Japanese devised a tactic to circumvent this

strategy. Suicide boats—midget submarines and small surface craft of every

description—slipped through the pickets and joined in the harassment of the

fleet.

On June 4 nature joined the forces of the Japanese. A

typhoon arose. The Small Boys were ordered to hunt refuge. The Sea Hawk

proceeded at maximum speed toward a cove on Tokashika island. The fury of the

storm hit her as she wallowed into the cove.

"Christ . . . a Jap ship!" Commander Madsen said shrilly

as he stared in the last light of dusk at the Riyuko Maru, which was

tossing on the turbulent waves near the cove's eastern shore.

Neither the Sea Hawk nor the Japanese tug fired at

each other then, or during the night. The winds were so malevolent and the waves

so ferocious that they did well to stay afloat. Other ships were less fortunate.

Seven auxiliary U.S. Navy ships were capsized by the typhoon. This terrible

storm sheered off the bow of the cruiser Pittsburgh. It gravely damaged

the Hornet and washed 17 fighter planes off this big carrier's flight

deck.

But fortunately for the U.S. cause, the typhoon was not a

sumonsong (the usual two or three-day storm). At 0912 the next morning the winds

suddenly abated. Immediately the seas began to diminish. Madsen, who had been

watching the Riyuko Maru since dawn, shouted to his gunners, "Begin

fire!"

Captain Tamashiro must have issued identical orders to his

juvenile crew and at the same moment, because simultaneously each ship fired at

the other.

An hour and a half later Boatswains Mate First Class

Donald Wilkes and Gunners Mate Second Class Ray 'Guns' Gartner climbed atop the

debris which had been the Riyuko Maru's bridge. They remained there until

the Sea Hawk disappeared over the eastern horizon. Then they leaped onto

the deck. "A couple hours ago I'd have thought that guarding 77 virgins was the

kind of duty a guy dreams about," Gartner said uneasily. "But now that we're

actually doing it I feel nervous or something."

"I feel likewise," Wilkes said. "If it was just a few

women I wouldn't. . . ."

He didn't finish. Someone was pounding on the hatch. The

sailors' eyes met. Then they went to the hatch. "Keep your M1 focused on it when

I open it," Wilkes said tensely.

Wilkes jerked open the hatch. An abrasive-featured

middle-aged Japanese woman glared up at them. She was Masaru Kichimato [12],

a lieutenant of the Iwasaki, an organization of combat-trained Japanese women [13].

She had been ordered to accompany the virgins to their destination, and to

maintain discipline.

"I didn't know that old biddy was down there," Wilkes said

to Gartner.

"I am not an old biddy!" Lieutenant Kichimato snapped in

excellent English. Wilkes' face reddened, and the angry woman said in the tone

of a Japanese officer who brooks no nonsense, "Step aside, cockroach. We are

coming on deck." The virgins could not be expected to remain below until the

American ship came for them, she said; therefore, they would spend their days on

the deck and retire to the hold each night.

This seemed reasonable. It would be barbaric to confine

the women to the tug's dank, gloomy hold until the U.S. ship arrived, which

might not be for several days, or even a week. Wilkes glanced at Gartner, who

nodded.

"All right," Wilkes said warily, "but no tricks. And at

dusk you go below again."

For the Americans it was an intriguing day. The virgins

milled around the tug's deck. They stared at the Americans with great curiosity

and when Wilkes winked at a particularly brazen girl she giggled and began to

approach him. But Lieutenant Kichimato bellowed to her and she went away.

"Something tells me I'm going to tangle with that old witch before this mission

ends," Wilkes muttered.

At about 1900 Kichimato ordered the virgins below. The

Americans bolted the hatch. They went to the bow and opened tins of the rations

which Commander Madsen had brought to the tug from the Sea Hawk. "I

wonder what they would be like? To make love to, I mean," Wilkes mumbled through

a mouthful of food.

This provoked a debate concerning the relative sexiness of

Japanese and American women. Since neither man had had personal experience with

Japanese women, or had even seen a Japanese woman until that day, their

discussion contained a high element of speculation.

After their meal the Americans lit cigarettes and lolled

on the bow's deck and stared at the hatch. "I wonder if we could get two of them

up here, without all the rest," Wilkes said hopefully.

"It's worth finding out," Gartner replied. "Some of them

certainly acted friendly."

He and Wilkes went to the hatch and opened it. "What do

you want?" Lieutenant Kichimato asked icily.

"We were wondering if a couple of the girls would like to

help us stand watch," Wilkes said.

Lieutenant Kichimato's reply is unprintable. Wilkes

slammed the hatch and locked it. "That old witch," he said shakily, "is going to

open her big mouth just once too often!"

Several cigarettes later he and Gartner decided to

alternate two-hour watches throughout the night. They were convinced that it

would be indiscreet for both to sleep at the same time. "I'd hate like hell to

be knocked off by a bunch of women," Gartner said. Wilkes agreed that this would

be a staggering humiliation, even though the victim wouldn't be around to hear

the jibes of his shipmates.

Gartner took the first watch and Wilkes sprawled on the

deck. But Wilkes did not immediately drop off to sleep. It was disturbing to

think of the Japanese women, and to hear their giggles through the deck's

planking.

Two days passed. "We have little food left," Lieutenant

Kichimato said, "When is the ship coming for us?"

"It should arrive any time," Gartner replied. "In fact, it

should have already been here."

When the lieutenant went away, Wilkes said, "I don't

understand it. Madsen said he'd send someone for us right away."

These men did not know that no one would come for them—no

one knew of their circumstances. An hour after the Sea Hawk had wallowed out of

sight two suicide Japanese Bettys crashed into her [14].

She went down in an awesome pyrotechnical display; her crew became additions to

Okinawa's dreadful casualty toll.

The next morning, Lieutenant Kichimato said, "We have

eaten the last of our food. Where is the ship from the vaunted American Navy?"

"We're going on the beach," Gartner said, "to look around.

Maybe we can find some bananas or something."

Because they did not trust her, the Americans took

Kichimato with them, going ashore in the leaky old boat which had been lashed to

the Riyuko Maru's starboard flank.

There were citrus fruits and yams on Tokashika. Fish swam

in the shallow waters which jutted from the cove. "Finding enough food for all

those women, three times a day, will be a tough job and we might have to do it

for several days," Wilkes said. "Why don't we bring them here and let them look

for their own chow?"

"How do you know we won't escape?" Lieutenant Kichimato

said with great sarcasm.

"We couldn't care less," Gartner said. "Especially if you

were included."

Wilkes glared at the woman. "Get into the boat," he said.

"We're returning to the tug. You're going to tell two of your beefiest girls to

row us back here, then bring the other girls ashore."

Kichimato said that she had decided to have the Americans

bring the food to her and the virgins aboard the tug.

"Get into that boat, you contrary old witch!" Wilkes said

between clenched teeth.

By noon the last of the virgins was ashore.

The girls did the work—Gartner and Wilkes supervising—and by

noon everyone had been transferred from the tugboat to the island.

The Americans threw a grenade into one of the inlets. It

killed numerous fish. Except for one which they kept for themselves, they gave

these fish to their prisoners. The women returned this favor with various fruits

which they had gathered in the jungle.

When the women completed their meal they arose and, en

masse, strode into the foliage south of the beach. The Americans, suspicious and

worried, swooped up their M1s and followed.

The Japanese came to a spring-fed pond which they had

discovered in their forage for food. Soon they were bathing in this pond. The

Americans sat on its bank. "It isn't every day," Wilkes said happily, "That you

get to see seventy-seven dolls take a bath."

The afternoon was uneventful but occasionally several of

the girls, after determining that Kichimato wasn't watching, looked appraisingly

at the Americans. "Tonight . . ." Wilkes said eagerly, ". . . old Kichimato

won't have her wards cooped up where she can keep an eye on them."

But after their evening meal, Lieutenant Kichimato said to

the girls, "you are forbidden to fraternize with the Americans!" The very

thought, she said, was degrading. Americans were uncouth barbarians who never

bathed.

This counsel was received with varying emotions. Among the

girls who were the least impressed were two who had evinced, with little

subtlety, an interest in the Americans. One of these was 17-year-old Toyada

Shigesetsu [15], the daughter of a Kyushu coal

miner—a beautiful young woman by any standard. The other was moon-faced Kenji [16]

Hotoyama, 19. She was sloe-eyed, vivacious and a flirt. A peasant's daughter,

she had been sold to the Imperial Army's Morals Endeavor Society after a rice

crop failed.

"As quickly as Kichimato goes to sleep," Wilkes mumbled,

"let's wander into the woods with those girls."

When darkness fell Kichimato ordered the Japanese girls to

sleep in rows which she designated, presumably to enable her to spot, at a

glance, if any were absent. Then she bedded down.

The Americans sat on the grass about thirty feet from the

Japanese. At intervals Kichimato would get up and look at her wards. Then she

would lie down again. "She can't keep that up all night—I hope," Wilkes said.

Midnight came. An hour had elapsed since Kichimato's last

inspection. Wilkes crept toward her. Then he returned to Gartner. "The old biddy

finally went to sleep." he whispered. "Let's go!"

Soon he and Gartner were in the forest with Toyada and

Kenji.

They were still there at dawn when Kichimato discovered

them. Her face quivered but she made no comment. Instead, she strode,

dejectedly, toward the beach.

The Americans and the Japanese girls followed. "She's up

to something," Gartner said worriedly. "Or else she would have kicked up a

rumpus."

They came to the beach. Kichimato knelt on the sand. She

began a cabalistic chant. She was explaining to her ancestors why she had failed

to fulfill her orders in behalf of the Emperor's kamikazes, the pilots of the

Divine Wind. But the Americans didn't know it. They knew nothing about Shinto,

the religion of Japan, and its reverence of ancestral spirits.

When Kichimato finished she rose to her feet. She turned

to the two sailors. "I despise you," she said. Thoroughly puzzled, they watched

her climb to the top of the cliff at the north end of the beach. She stood

poised for a minute, then leaped into the rocky surf. Her broken body was

carried seaward by the morning's ebb tide.

"I don't understand Japanese at all," Wilkes said shakily.

"I didn't like her," Gartner mumbled, "but I wish she

hadn't killed herself."

The virgins, the Americans soon discovered, were less

shaken by Kichimato's suicide than they were. In fact, the girls seemed to be

comforted by the knowledge that their harsh disciplinarian could no longer

harass them. They conversed cheerfully during their breakfast. Then they went to

the pond.

In every group a leader emerges. The next day a superb

specimen of Japanese femininity came to the Americans. She was 19-year-old Keizo

[17] Yamazaki, the daughter of a silk weaver in the

Nishijin section of Kyoto. Because her father had not paid her mother the honor

of legal marriage she had been, in local society, a pariah. So she had

volunteered for the assignment that this would afford prestige and status. The

Japanese looked upon kamikazes as demigods whose valor and sacrifice would

reverse the fortunes of the war.

"Japanese virgins very unhappy," Keizo said in faltering

but understandable English. There would be trouble, she said, unless the

Americans showed no favoritism. She suggested that each evening the Japanese

determine, by lottery, the two who would spend the night with the Americans.

"Then no virgin lose face," Keizo said.

"Fair enough," Wilkes said happily. Then he said, "Something has been

bothering me, Keizo—are you girls really virgins?"

They were spiritual virgins, the intrepid little Japanese

replied. The Americans did not ask for an explanation. They were convinced the

Japanese were unfathomable.

One idyllic day followed another. The girls sang and

played their samisens. The Americans spent their time fishing, or swimming with

the prisoners. The blood and horror of the Okinawa campaign seemed unreal.

But the marooned men talked often of the Sea Hawk

and of their shipmates. They were certain that a major disaster had befallen

them, and this conviction was disturbing.

In the meantime, the Navy Department, believing that

Wilkes and Gartner had gone down wit the Sea Hawk, sent the dreaded

"Regret to inform . . ." telegrams to their parents. It was one of the quirks of

the war that while those heartbroken people mourned their sons' deaths these men

were frolicking with Japanese girls on an obscure Pacific island.

For thousands of other Americans, though, the war was no

frolic. The defenders of Okinawa made the invaders pay a ghastly price. But the

Americans were determined and their resources were unlimited. Organized Japanese

resistance collapsed June 21—after 82 days.

A week later the cruiser Vicksburg (CL86) glided

into the cove of Tokashika island [18]. Landing

parties from this big ship, and others, were going ashore on each of the

region's numerous islands. They were seeking survivors of ships and aircraft

which had been lost during the campaign.

Wilkes and Gartner, concealed with the Japanese women in a

bamboo thicket, stared unhappily at the Vicksburg gig as it sped across

the cove. It was occupied by three marine fire teams, a young lieutenant, and

several Navy men.

"If we were lost on a rock where we were starving or

something they wouldn't find us in a 100 years," Wilkes mumbled. "But here,

where nobody's asking to be rescued, they're right on the ball."

A coxswain expertly beached the gig. The marines leaped

onto the beach and, cautiously watching the jungle, began to advance toward it.

"Hold your fire!" Gartner shouted. The war had not yet ended; there was grave

risk that these combat-tempered marines, hearing the voices of the Japanese

women, would sweep the thicket with fire from their BARs.

"Come with us and you won't get hurt," Gartner said to the

Japanese. Then he and Wilkes, followed by these apprehensive women, walked out

of the thicket.

The marines stared incredulously. "Who," the lieutenant

demanded finally, "are these dolls?"

"Japanese doxies, sir," Wilkes replied casually.

"And just you two men have been here with all of them?"

"Yes, sir," Wilkes said. "For three weeks."

The marines stared at Wilkes and Gartner with open envy;

women had been available to few of the troops in the central Pacific.

This was a situation which left the lieutenant

dumbfounded. In the classic way of the military he decided to pass the buck to

his superior, the Vicksburg's commander, Captain Lawrence C. Grannis,

USN.

Several minutes later Captain Grannis came ashore. He

looked unhappily at the women. "This," he said, chewing thoughtfully on his

cigar, "presents a problem." There were, he reflected, no facilities on a

warship for transporting women.

The captain returned to the Vicksburg. He radioed

CinCPac at Guam. An hour elapsed while the brass at CinCPac discussed the

disposition of the 77 prostitutes. Then they radioed Captain Grannis. "Confine

the Japanese females to the chief's quarters," the message stated, "and proceed

immediately to Saipan."

The Vicksburg dropped anchor in Saipan's Tanapag Harbor on

July 1, 1945. Immediately the Japanese women were interned in the Charan-Kanoa

stockade. The next day, in one of the inexplicable snafus of the war, they were

assigned as instructors in the big prison camp's Education, Recreation, Religion

and Welfare Department.

Meanwhile, Wilkes and Gartner were assigned to the General

Service pool at Camp Calhoun. Several days later Wilkes was ordered aboard the

destroyer Trippe [19] to replace a

boatswain's mate who had been immobilized by an appendectomy. Within a few days

Gartner joined the ship's company of the escort carrier Cape Esperance.

Both of these men—news of their bizarre adventure had preceded them—were

considered by their shipmates as gallants who had had the maximum experience.

Six weeks later the war ended. Soon, along with many of

Charan-Kanoa's 18,000 other Japanese prisoners of war, the 77 virgins were

transported to Nagoya, a seaport on Honshu island. Then, upon the orders of U.S.

Military Government officials, they were returned to their homes.

As for Wilkes and Gartner, their incredible saga was told

and retold in every ship in the Fifth Fleet, and embroidered on so that any man

who could say he knew them personally was considered a celebrity.

Notes

1. There is no record that the Riyuko Maru

ever existed.

2. Tokashiki Island, not Tokashika Island, is

located about 20 miles southwest of the southern tip of Okinawa. Tokashiki

Island is the largest of the 22 Kerama Islands. Tokashika Island does not exist.

3. LCI is the acronym for landing craft, infantry.

4. A fundoshi is a traditional Japanese

undergarment for adult males.

5. An Airsaki does not exist, but the reference

here is probably to Arisaka rifles used by the Japanese Imperial Army.

6. Both Ikeda and Tamashiro are Japanese family

names rather than one being a family name and the other being a given name.

7. It is inconceivable that a tug would be

transporting women in early June 1945 to Miyako Island, which had been subjected

to repeated Allied air attacks since late March 1945 (Samples 2010, 36-105).

8. No reference could be found that an LCI named

Sea Hawk ever fought in WWII.

9. The military leaders in Japan did not hear of

the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt until April 13, 1945, so it would have been

impossible for them to decide on the date of April 12 for the mass kamikaze

attack after hearing of the American president's death. Roosevelt's death certificate gives the time

of death as 3:35 p.m. on April 12, which would have already been the morning of

April 13 in Japan due to the time difference.

10. Battleship New Mexico (BB-40) was hit

by a kamikaze aircraft on May 12, not April 12, 1945.

11. A listing of U.S. Navy ships damaged or sunk

by kamikaze attacks (Rielly 2010, 322) indicates 261 men died on April 12, 1945,

rather than the story's inflated figure of 2,000 men.

12. The Japanese family name of Kichimato does

not exist.

13. No reference could be found that such a

group named Iwasaki existed in WWII.

14. Betty bombers never carried out any official

suicide attacks as part of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps. Instead, the

Japanese Navy used them to carry ōka rocket-powered glider bombs into battle so

they could be released to attack Allied ships.

15. These two names do not exist in Japanese.

16. Kenji is a male, not a female, name.

17. Keizo is a male, not a female, name.

18. The light cruiser Vicksburg

(CL86) could not have been at this small island a week after June 21, 1945,

since the ship left the Okinawa area to head for the Philippines on June 24.

19. The destroyer Trippe actually

existed, but she was decommissioned in 1931 after seven years of service in the

U.S. Navy.

Sources Cited

Rielly, Robin L. 2010. Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A

Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships, by Aircraft

and Other Means. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Samples, Fredio. 2010.

Wings over Sakishima.

Privately published.

|