Kamikaze

by John Hersey

Life, July 30, 1945, pp. 68-75

Introductory Comments

John Hersey, famous American journalist and writer who

wrote the critically acclaimed article "Hiroshima" for The New Yorker in

1946, was also the author of an eight-page article about kamikaze pilots that

was published in Life magazine less than three weeks before the end of

World War II. At the time of the Life article, the U.S. Navy already had

released many details about successful kamikaze attacks on American ships, but

some facts such as identification of specific ships for certain attacks were

still withheld from the media.

The article still uses some disparaging terms to

describe kamikaze pilots with only limited information directly from very few

captured Japanese airmen. Several places in the article refer to Japanese media

as sources for information. The author's tone is not hateful toward Japanese

kamikaze pilots but makes clear his side in the conflict. The strongest words to

depict Japanese pilots are after naval cadets have completed their initial

training: "They have become terrified automatons. They have no

individuality. They are full of zealous, pitiful reflexes. They are, by our

standards, crazy." Hersey ends the article with words concerning the desire of

Japan's leaders to have all of their people be ready to die if the enemy

invades: "They have systematized suicide; they have nationalized a morbid,

sickly act."

Naoko Shibusawa, in her 2006 book America's Geisha

Ally [1], thinks Hersey's article was a

"favorable depiction of the 'suicidal corps.'" She writes, "John Hersey authored

an article on kamikaze pilots that portrayed them as generally crazed and

desperate, but he also included a description of a more sensible kamikaze." She

thinks that the article's story of a pilot at Clark Field in the Philippines

"sounds somewhat dubious," but "presenting any Japanese—especially

a kamikaze pilot—as an ordinary human being with a normal desire to live marked

a significant departure from the standard wartime images."

The Jap air force has turned itself into a suicide weapon. . .

. Its weirdly trained pilots seek glory in death. . . . They cannot win the war

but do great damage

One day during the Okinawa campaign a Japanese suicide plane came in low over

the water to attack a warship on which Admiral William F. Halsey was the senior

officer. The plane came at deck level on the portside and hit. There followed

the usual confusion of such moments on shipboard. Admiral Halsey quickly told

the boatswain to pipe an order. It was not one of the usual hasty commands

directed to fire fighters, damage-control parties and the various personnel of

emergency. It was, instead, pure Halsey.

The boatswain made his ridiculous piping sound and then roared into the

ship's public-address system, "Now hear this! Sweepers, man your brooms. Clean

sweepdown fore and aft."

When he tells this story, "Bull" Halsey adds a fillip. He says that in the

time that it took him to go down from "flag country" in the superstructure to

the deck, where he wanted to inspect the damage, the crew had removed every

trace of the attacking aircraft and machinist's mates had already begun, in the

shops below, to fashion rings, bracelets, paperweights, napkin holders and other

souvenirs from the wreckage of the plane.

Admirals of the U.S. Pacific fleets have been at some pains to scoff at the

weird form of self-inflicted glory that the pilots of suicide planes seek. More

deliberately and less spectacularly than when he tells the story above, Admiral

Halsey has called the Japanese air force fifth- and sixth-rate, "instead of

third-rate" as some people had thought. Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher has said

that suicide planes were "not more than 2% effective," and he added, "They don't

worry us very much." Admiral Chester W. Nimitz himself has said that suicide

planes have enjoyed "negligible effect on the continuing success of our

operations."

In spite of these sanguine and breezy announcements Japanese suicide planes

have been no joke. They have been far more than a mere annoyance. They have done

much more damage in the Pacific than most people in the U.S. realize. They have

killed and hurt many men—656 on the Bunker Hill, 323 on the Nashville,

337 on the Ticonderoga, 62 on the hospital ship Comfort and many,

many others, announced and unannounced. The Navy has admitted that the Okinawa

campaign brought casualties, mostly caused by suicide planes, of 9,731 men,

which compares with 3,385 at Pearl Harbor.

Suicide planes have caused a great amount of material damage as well. The

Japanese have claimed, with their usual enthusiasm, 326 ships sunk or damaged:

15 carriers, 6 battleships, 49 cruisers, 70 destroyers, 59 transport and other

small craft. The Navy has so far admitted damage to 19 ships. Since Tokyo Radio

has declared that the entire Japanese air force is now suicide-bent, it can be

presumed that some others among the 80-odd ships hit during the Okinawa campaign

received their blows from suicide planes. The announced damage includes three

carriers. Admiral Mitscher, in issuing his declaration of unworry, showed

himself cool to an extraordinary degree, since he had been forced to ride in a

boatswain's chair from one carrier, the Bunker Hill, which had been badly

hit by suicide planes, to another, so far not identified, which was soon also

hit [2].

Suicide planes cannot turn the tide of the Pacific war any more than

buzz-bombs did in Europe. The peak of danger has already largely passed. During

the first three months of 1945 Navy and Marine air units claimed a 9.4-to-1

ratio of kills over the Japanese. By April, after B-29 bombings were beginning

to be felt, Admiral Nimitz was able to announce that for the first time in the

Pacific war we were destroying planes faster than the Japs' ability to replace

them. On April 15, Japanese plane strength was about 8,000 planes. Now it is

less than half of that.

Nevertheless, Japanese suicide can and will make victory more expensive. It

is a strange, unsettling weapon for human beings of the 20th Century to face. It

is, indeed, no joke.

"For one man, one ship"

The Japanese organized self-destruction in the late summer and autumn of

1944. In all branches of the service suicide tactics were worked out in detail.

The appeal was to fanaticism; the excuse was economy. One man was to slay a

thousand. The slogan of all naval suicide forces was, "For one man, one ship."

Tokyo Radio said, "In view of present conditions, it is imperative that all

troops have a thorough understanding of tactics of a suicidal nature, with each

man destroying a plane, a ship or a tank in order to smash the arrogant enemy,

who depends on material superiority."

The naval air force was the first to devise a successful Special Attack

Force, as suicide units in Japan are called. With typical Japanese mixture of

science and voodoo, the Jap navy called the first unit Kamikaze, or

Divine Wind, after a gale which, in 1570 during the Yuan dynasty, considerately

[3] wrecked a Mongol fleet which was bearing down on the Japanese islands with

intent to invade. From this name, also given to later navy (but not army)

suicide units, has come the generic term usually applied by the U.S. Navy to all

sorts of enemy suicide attack from the air. Army units were also organized

during the late summer and autumn of 1944. These were called simply Special

Attack Forces, Tokubetsu Kogekitai, usually abbreviated to TO [4].

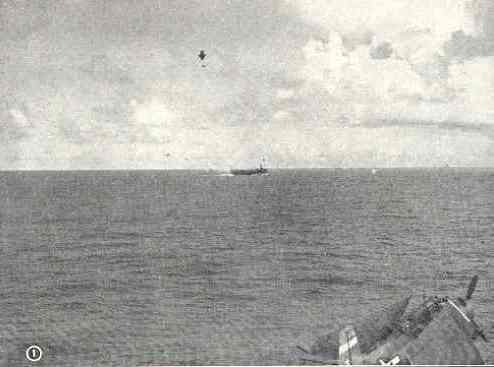

Carrier "Suwannee" stands by to take aboard one

of its planes (left) as Jap

plane (arrow) dives

"Suwannee" sights kamikaze, waves oncoming

plane away, directs antiaircraft

fire at Jap

Navy Hellcat swerves off course, nears kamikaze

but is not able to prevent

Jap from crash-diving

Jap pilot makes perfect hit on "Suwannee's" island

(superstructure), the

nerve center of the ship

Smoke billows from baby flattop's deck and

superstructure as Grumman Hellcat

flies off

Blazing, "Suwannee" turns about. Battle was last

October in Leyte Gulf, when

Japs suffered heavily

According to Tokyo Radio, the first organized suicide attack took place on

Oct. 15, 1944. That day Vice Admiral Masabumi [5] Arima, who had trained the

first Kamikaze force [6], showed up at his unit's air base in the

Philippines with his shoulder boards stripped off and the characters indicating

his rank scraped from his binoculars. A mission was being mounted against U.S.

task forces which had appeared in the waters east of the Philippines and Admiral

Arima announced his intention of going along in the lead plane "with

determination never to return." Staff officers tried to dissuade him but he

said, "Unless we seize this opportunity to hit the enemy, the traditional spirit

of the Japanese navy will be spoiled. You should know how to take care of this

unit after my death." With that he took off. Hours later he sent a brief

wireless report, "Going to body-crash against enemy aircraft carrier. Hope

everybody will exert all-out efforts." Tokyo Radio said, "Eyewitness reports

brought back to this base revealed Vice Admiral Arima scored a direct torpedo

hit on an enemy regular aircraft carrier and then crash-dived against the same

enemy warcraft." Unfortunately for Vice Admiral Arima's shade, now presumably

hanging around the remains of the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, to which the spirits

of Japanese heroes are supposed to repair after death, no U.S. carrier, regular

or converted, was hit that day.

But ten days later, on Oct. 25, the story was different. Off Leyte Gulf the

Japanese mounted a suicide attack which was large-scale, determined, coordinated

and effective. An escort carrier and a destroyer were sunk and several other

units damaged. During the Leyte battle other attacks followed; altogether 40

navy and army suicide units took part. From that time the U.S. Navy also began

to take Japanese suicides seriously. As the Pacific campaigns developed, the

Japanese mounted attack after attack, climaxed by an assault of more than 500

planes off Okinawa on April 6, 1945.

The only thing which has been consistent about all these attacks has been

inconsistency. Certain reports have filtered back to the U.S. press which have

given a widespread impression of uniformity—an impression, for instance, that

all pilots in suicide attacks are locked in their planes, that they all wear

ceremonial robes, that their training has been uniform, their tactics

standardized. Nothing could be further from the truth. The most that can be said

is that there are apparently two types of units: those which have been organized

specifically as suicide groups and those which are haphazard, spur-of-the-moment

formation. But even among organized suicide units there has been a wide variance

of technique from the moment of the units' activation to the moment of impact

and death. And even within single squadrons there apparently has been great

latitude, for each individual has considerable choice in his particular path to

Japanese glory.

There is, in the first place, no uniformity whatsoever in the way suicide

units are organized. When the first units were formed the army and navy both

issued calls for volunteers. A tremendous propaganda campaign followed these

calls. There were repeated broadcasts about three brave aviators who had crashed

their fighters into enemy planes and who were said to be hobnobbing with Japan's

suicidal greats at the Yasukuni Shrine. One broadcast told of a naval commander

who restrained his young fliers because they were overly eager to fly out on

their last mission. "There is no need to hurry so," he was quoted as saying.

"Your chance will come soon." But the young fliers replied (according to Tokyo

Radio), "There are swarms of the enemy around. If we do not hurry, the enemy

will flee."

|

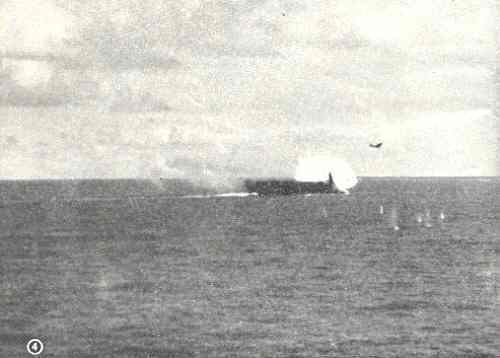

Kamikaze attack on the U.S.S. Laffey is diagramed above.

Twenty-two Jap suicide planes sighted destroyer off Okinawa April 16 and for

more than two hours bombed and crash-dived in a wild and apparently unorganized

attack. Five Jap Kamikazes crashed amidship, four bombed it, three tore

off parts of the superstructure. But the Laffey managed to stay afloat

and crawl back to the U.S. for repairs. Only one Jap pilot (no. 12) may have

managed to stay alive through the engagement. Of the Laffey's crew, 60

were wounded, 30 were dead or missing. |

The entire air force volunteers

The propaganda also appeared in the press and it continued through the

autumn, even after the first units had gone into action. One typical article on

suicide units said, "The faithful Kamikaze special attack plane

units—divine eagles, bombs composed of men and planes, which plunge down on

enemy ships, young, ruddy-faced men—are ever ascending the glorious road,

repeatedly dealing crushing blows to the enemy. Each man ties a white silken

scarf firmly around his head. Their friends wave sad farewells to these

broad-shouldered youths who are without even parachutes. The skies are slowly

brightening. . . ."

But the Japanese mentality defeated the plan to gather suicide units by

volunteering. According to the Japanese, volunteering was forestalled by "a mass

show of patriotism" in which every pilot in the army air force asked to be

assigned to suicide duty. There is evidence that there may have been some

persuasion behind this all-out enthusiasm, but in any case general volunteering

was soon called off in the navy as well as the army.

After that units were formed in various ways. Sometimes an order came down

from above designating an entire squadron; often this seems to have been done at

the eleventh hour. Sometimes a commanding officer volunteered his outfit. There

is a story to the effect that in one squadron three fliers go their chance for

the glorious honor of suicide when an officer came up one day on parade and

said, "I want three volunteers for suicide duty—you, you and you."

Similarly, training varies from extreme thoroughness to less than a lick and

a promise. Some pilots are no more than 16 years old. These apparently have been

drafted into the army, given about a two weeks' indoctrination course in ardor

for death, plus about a dozen hours of flying instruction during which they

learn to take off and make a few simple maneuvers, then have been bundled into

white funeral robes and packed off to kill themselves [7].

Some pilots, however, have been through extensive training especially for

suicide: certain navy volunteers receive a fantastic education. At a typical

training school the candidates are young men between 19 and 24 years old. The

first stage of their course, which is called preparatory training and lasts

about a month, is the period of "spiritual intoxication." The major subjects are

physical training, general principles of land and sea warfare, code

instructions, the principles of Bushido and so forth. On the one hand

great emphasis is put on physical perfection, the subjugation of the body, a

"slavish" life. The candidates are not given a moment's rest all day, and the

days are long. On the other hand a mystical and gloomy atmosphere is wrapped

around the men. There is a shrine inside the squadron's quarters where, two or

three times a day, the candidates go and whisper to the dead of the naval

aviation corps. From time to time the candidates are made to swear before these

spirits, "We are certainly coming after you." Each cadet in the preparatory

course is closely followed by a veteran cadet, who has finished the preparatory

course and who constantly murmurs into the cadet's ear depressing and

masochistic messages, "Be brave. . . . Make use of all your vigor and bodily

strength to overcome your physical pains. . . . Orders from superior officers

must be fulfilled without fail. . . ." In physical training the men do

anachronistic, formal, dancelike exercises. With a heavy samurai sword they

slice the whistling air and shout together, "Cut a thousand men!" and other

battle cries such as the one which is supposed by the baseball-loving Japs to

strike dismay into American hearts, "To hell with Babe Ruth!" The also learn

slogans such as "Sure hit, sure death."

At the end of a month of preparation the men are "intoxicated" enough. They

have become terrified automatons. They have no individuality. They are full of

zealous, pitiful reflexes. They are, by our standards, crazy. At this point

flying instruction commences. Discipline is now tightened even more. The most

trivial operations of daily life, down to eating and breathing itself, are

regulated by rigid formulas. The section commander, usually an experienced

pilot, lives with his cadets and keeps urging them to have an appetite for

glorious death. The length of this period of instruction depends on the tactical

situation. The last lecture the section commander gives his men is this, "I have

taught you all that I have learned from our seniors. There is, however, the

lesson of death which I have not yet taught you. Be careful to heed the

manner in which I am to die!"

After their training the men are assigned their stations, their planes and

their equipment. There certainly has been no standardization of plane types for

suicide missions. Various Kamikaze and TO squadrons have used the types

nicknamed Zeke, Val, Oscar, Nate, Ida, Tojo, Tony, Judy, Betty, Frances, Irving,

Dinah, Lily, Jill, Sonia, the obsolete Kate and even the trainers Hickory,

Cypress and Spruce. The equipment of one suicide plane included obsolete landing

lights and rusted inner parts and its paint job was just like that of the planes

which bombed Pearl Harbor. Another plane had a plate on its engine showing that

it had been built and inspected in 1940. A float-type plane, which was brought

down by the splash from a five-inch shell fired by the destroyer Hugh W.

Hadley, blew up the moment its pontoons struck the water. Presumably the

pontoons were filled with explosive and equipped with contact detonators.

Sometimes the planes the men finally get must be a shock to them. After their

training, in which they have been given the best of equipment, quarters and

food, many of them could not help being bitterly disappointed to be shipped to

forward bases and receive old crates which, indeed, can just about make the

one-way trip to suicide. But Japan's best remaining planes are also thrown into

suicide attacks. Most attacks these days are made by perfectly good Vals and

Zeke 52s. Whatever the plane, the pilot is supposed to learn to love it as if it

were part of his own body.

The one thing which can be said to be fairly uniform practice among suicide

units is the ritual before missions. This would naturally vary with the locale

of the field, but it is always elaborate and highly emotional. It consists of

the last spree for the doomed men and, just before take-off, his own funeral.

The night before, the pilot usually attends a banquet at which, after suitable

toasts served with suitable blandishments by geisha girls, he gives away his

belongings—his watch, his clothes, his everything. His possessions acquire a

kind of talisman quality with his death. One squadron banded together all its

money and gave it to the government for aircraft production. The government

decided to use the fund to make towels, embroidered with the Rising Sun and the

word Kamikaze and put them in aircraft-factory bathrooms to remind

workers of these brave men.

Before the take-off the entire personnel of the base gathers on the field.

Orders are read to the men, who are told that the Emperor himself gave them. The

commanding officer makes a speech. One such speech, as quoted by Tokyo Radio,

went like this, "Whether our nation can triumph or not depends on you. For His

Majesty the Emperor and for your country, I ask you to give me your lives. I

know your sole regret is to die without knowing what damage you have caused the

enemy in your death dive. But rest assured. The planes which follow you have

orders to ascertain your achievements and report them to me. I in turn will

report your deeds to His Majesty the Emperor, so I want you to fly on your

mission without a single worry."

|

Baka bomb, Jap's newest suicide weapon, is not in widespread use. U.S.

Navy experts call it the "perfect missile." It is man-driven, rocket-propelled

plane borne to within a few miles of its target, then released by its mother

plane—usually a Jap medium bomber. It carries 1,135 pounds of

explosives. Light and small (19 feet, 10 inches long) it has a range of only 55

miles and is not very maneuverable. Baka carries no defensive weapons,

depends on its great speed (up to 535 mph) to reach target. Warships are

baka's usual targets but they have also attacked B-29s over Japan [8]. |

First the pilots pretend to die

Then, symbolically, the men give him their lives. They bind the white band of

death on their foreheads, and in some cases the white robe as well. Some have

farewell poems inscribed on their headbands. One, according to Domei, had

written,

When I fly the skies

What a fine burial place

Would be the top of a cloud!

The men hand the commander the little white boxes which the Japanese use for

human ashes and which are, in effect, the men's own coffins. The commander tells

each man that he will see that his family receives the box. From that moment

they are considered dead and they are worshiped as such by the personnel at the

base [9].

The commander bids farewell to the men, saying something cheery to each man,

such as, "I'll meet you at the Yasukuni Shrine." The pilots man their planes and

take off. In some cases they circle the field three times as the personnel below

stand salute.

The costumes the men wear seem to be strictly up to them. The first instance

of a curious costume found on a pilot in a wrecked plane was a skin-tight

green-and-white silk uniform, almost like a jockey's clothes. Most men have worn

orthodox flying clothes. Some seem to have given so much away the night before

that they fly to death in nothing but a breech clout [10]. Recently more and more

suicide pilots have been dressed in the white silk ceremonial robe which, in the

hara-kiri ritual, symbolizes honorable death [11]. A Marine fighter pilot in action

in the Okinawa area amused himself, while attacking a suicide plane with an

inferior pilot, by flying wing on it for a time, and he later reported, "The Jap

pilot opened the cockpit cover. . . . A white material flowed from his person

and streamed in the wind. It appeared to be an Arab-type robe with large

sleeves. It is possible that the robe suit had a white hood attached, but of

this I could not be certain."

The pilots are neither locked in nor chained to their planes. The impression

that they were locked in came from a widely printed news dispatch from Kunming,

China, which was apparently based on inadequate information. The story that they

were chained arose from one case in which the pilot had manacled his feet to the

pedal controls of his plane. There has been no other instance of this practice.

Probably the pilot in that case was unsure of his own courage and used the

manacles as a check on himself. Although the Japanese radio states that suicide

pilots go off without parachutes, several cases of men bailing out have been

observed, and the action report of one ship which came under attack stated,

"Oil, gasoline and parts of the plane were all over the ship. Most of the pilot

was in the flying bridge and his parachute hung from the yardarm."

The men carry an ugly freight. Until recently there has been no uniformity in

ordnance. Planes carried bobs, shells, torpedoes. One had a Type 89 50-mm.

mortar shell which had not been modified for nose detonation and so did not

explode; this indicated a hastily mounted suicide attack. Now more and more

planes carry a 550-pound bomb, either armor-piercing or semiarmor-piercing. The

light load of gas for a one-way trip makes it possible for planes to carry far

more than their rated load of explosive. One Frances was estimated to have 3,000

pounds aboard. Sometimes the bombs are shackled to the planes, sometimes not.

The planes have one mission only: to go in and attack, regardless of opposition.

In the case of army planes (and the same is probably true of most navy planes)

all guns and ammunition are removed before take-off [12]. The Japs feel that the

extra speed pilots would get from the lightened plane would enable them to avoid

engagement with enemy fighters. Multiple-seat planes like the Val go into attack

with the rear seat, usually occupied by a defensive gunner, empty [13].

Occasionally the planes' wings have been wired to set off the explosive charge

on the slightest contact.

Some Japanese suicide pilots like all this and some do not. Quite a few have

shown something less than the fanatical spirit which is expected of them. An

American officer translates the complaints of one Japanese, "a Brooklyn-type

Jap" captured off Samar Island, as follows: "I come to this Clark Field here a

couple days ago and I have nothing to do so I go out to look at my plane. I find

some dope of a mechanic has wired the bomb to my plane. I'm sore, I give the

mechanic hell. He says, 'Very sorry, orders.' What are they trying to do to me?

I go to headquarters and tell them what this dumb bastard done. They say, 'Oh,

we all do that now.' I say, 'You do it, not me! I don't like this wiring

business.' So what do they do? They arrest me. All night I'm under guard. I see

I got to get cagey, so in the morning I say, 'Okay, I'll take this ride for the

Emperor.' So they take the guard off me. Pretty soon I see my chance, I get my

parachute in the plane. We go out on this mission, it looks lousy to me, so what

do I do? I jump."

Even some instances which the Japanese radio has chosen to praise may be

figured two ways: perhaps the pilots were heroic, perhaps they were very scared.

One broadcast, for instance, told proudly of a Corporal Yamamoto who took off on

April 12 with his TO squadron to attack the ships off Okinawa. The boy was said

to be burning with ambition to die for the Emperor. After a while his plane came

chugging back with alleged engine trouble. The boy wept bitterly that he had

missed his chance. At the field they said, "Never mind, Yamamoto, you can go

tomorrow." It happened that there was not another strike until the 16th. He took

off. After a while his plane came chugging back; engine trouble; tears of

disappointment. Yamamoto was so disappointed that this time he disappeared. He

was found in the hills, weeping bitterly that he had failed the Emperor. He was

brought back to the field and given another chance the next day. The plane

revved up nicely. Suddenly Corporal Yamamoto jumped out of the plane. This time,

according to Tokyo Radio, he did not cut for the hills; instead he ran around in

front of the plane, patted its nose, bowed twice, got in, took off and, though

they listened for that faulty engine late into the evening, he never came back.

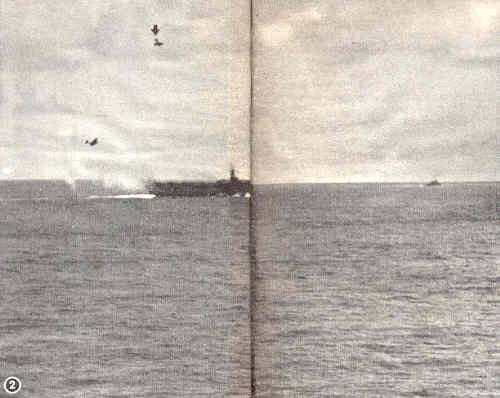

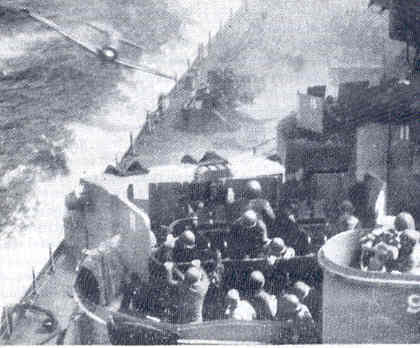

Zero bores in on Admiral Halsey's flagship. Moment later

it flew over this gun battery and hit the superstructure,

starting small fire,

then crashed into the sea [14].

There are, however, plenty of pilots who really do seem to want to die for

the Emperor. The pilots who survive and are captured can be assumed to be mostly

malingerers and malcontents who care more about what happens to their earthly

bodies than how their spirits make out later [15]. There are hundreds who press the

attack home for every one who surrenders. Even some of those who are captured

are zealots. One man, an expert fighter pilot of long experience, closed for an

attack and found AA fire so thick that he followed the instinct of an old hand

and took evasive action. Then he remembered that he was on a mission on which he

was not supposed to turn away. He swung back into the attack, but his plane was

shot down. He was heart-broken that he survived and tried several times to kill

himself in the brig of the ship that picked him up.

The reductio ad absurdum of this type of determination was set forth

in a broadcast over Tokyo Radio by a certain General Endo. He told of a pilot

who had flown to attack, had met bitter opposition and had had both his hands

shot away. He flew all the way back to Japan, said General Endo, with his mouth

around the joy stick, so that he could plan further action against the enemy.

This, the general said, was an example of Yamato Damashii—superhuman

Japanese.

Pilots meet death in their own ways

The difficult and violent conditions at the time of the attack, coupled with

varying degrees of zeal and experience in the pilots, account for the extreme

differences in tactics which suicide pilots employ. No matter how standardized

training might become, each pilot would meet death according to his own genius.

There are certain general outlines of tactics which both army and navy pilots

employ. The two principal attacks are 1) a long, steep glide and 2) an approach

only a few feet above the water, sometimes so low that the propellers make a

wake, with a sudden climb and dive just before the target. There are, of course,

many added twists. Some planes have flown right over the target and then

suddenly have swung back to hit it before AA could be trained around. In

attacking all types except carriers, the planes concentrate on the bridge

structure where they hope to knock out the personnel and machinery of command,

communications, gun controls and so forth. With carriers the standard attack is

on the flight deck. Other tendencies are concentration on ships isolated from

heavy antiaircraft fire, such as the gallant destroyers out on picket duty,

which have borne much the greatest weight of suicide attacks; simultaneous

attack from two or more planes, to confuse gunnery defense; good use of cloud

cover, the sun, land masses and other tricks to confuse spotting; and repeated

attacks on ships which have already been hit (the H.M.A.S. Australia took

aboard five suicide planes without sinking; the U.S.S. Laffey took five

suicide hits, four bomb loads and three planes which grazed the ship).

But within these broad frames there are infinite variants, arising especially

from the differing quality of pilots. One Marine fighter pilot who shot down two

Kamikaze planes within a few moments reported, "In my opinion both pilots

were poorly trained. Neither took any evasive action except kicking rudder and

skidding. It appeared they were trained for Kamikaze duty and nothing

else." Many pilots probably were flying their first mission. On the other hand

some attacks come at night and must be flown by experts. After one crash an

aviator's blouse was recovered which showed him to have been at one time a

carrier pilot, the most experienced type of Japanese aviator.

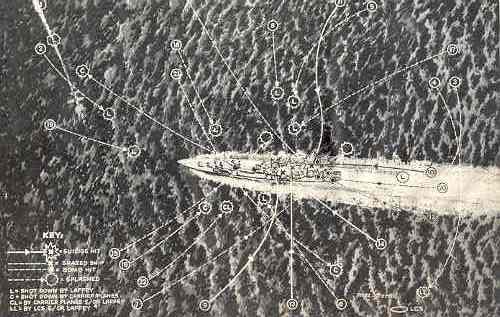

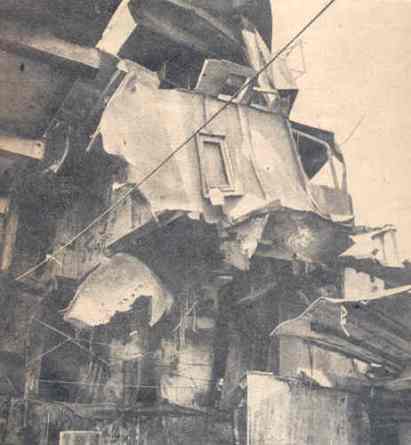

"U.S.S. Pinckney," hit by Kamikaze off Okinawa,

lost

44 men, including 18 Okinawa wounded who were

aboard transport. The ship is

now in U.S. being repaired.

How skillful the pilots can be was indicated by the man who flew a Val in an

attack on a U.S. warship on March 25, 1945, off Kerama Rettto. As soon as the

vessel opened AA fire the Val turned away in a great circle and firing ceased.

Simultaneously with "cease firing" the Val swung in again. During his long

approach the Val complicated the gunnery problem by zooming, climbing, slipping,

skidding, accelerating, decelerating and even slow-rolling. When he had closed

range to 4,000 yards he began coming in first with steep banks and then

executing continuous, unrhythmical right and left skids at an altitude of about

150 feet. At 1,200 yards the plane was hit and began to smoke positively and

blackly, and it came on. It passed over the stern at 100 feet and zipped over in

a vertical crash directly into the still rapidly firing guns of a 40-mm. mount.

A marine discovers the "gizmo"

It was on March 21, 1945, that the Navy discovered a new wrinkle in

Kamikaze. An ensign named Ward, flying a fighter plane from a U.S. carrier,

dived on a formation of Bettys from above and astern and flew under the entire

formation, about 2,000 feet below it. He looked up and saw that each Betty

carried under its belly an object which looked something like the buzz-bombs

Ward had seen in pictures. Whenever a Betty was hit by fire from U.S. planes,

she released her baby, which glided down at about a 30° angle, in some cases

trailing a light-brown smoke. The baby was at once dubbed "gizmo," which is

Marine and Navy usage for any old thing you can't put a name to.

Gizmo turned out to be baka [16]. The latter is a Japanese word meaning

idiot or fool and it is the name which Americans gave to this winged,

rocket-propelled, human-guided bomb. Baka has much in common with both

the German buzz-bomb and the winged rocket bomb which Germans released from

parent aircraft; there is evidence that the Japanese had German help in

designing baka. But there is the added Jap touch: human life is

considered as cheap as an automatic steering mechanism. The human steering gear

is, no doubt, more efficient. Baka may be stupid, but the Navy has also called

it "the bomb with a brain."

Baka is carried to within a few miles of the target at heights up to 27,000

feet and then released to glide to the target. Its maximum range is about 55

miles. With the help of three rockets, which push the plane for only about three

miles, it can attain a speed of 535 mph in level flight and 618 mph in a dive.

Baka is 19 feet 10 inches long and has a wing span of 16 feet 5 inches.

At the highest point, where a transparent plastic bubble bulges out of the

fuselage, it is only 3 feet 10 1/4 inches high. Nearly a third of the length of

the plane is taken up with the business end—a warhead weighing 2,645 pounds and

containing 1,135 pounds of trinitroanisol, which has about the same sensitivity

and power as TNT or picric acid. The one-trip pilot sits in a small bucket seat

and controls the bomb with a standard joy stick and foot-rudder-bar. Before him

he sees an instrument panel with an intercommunication switch and lights by

which (together with an electric horn) he can communicate with the parent plane

in code until he is launched; a rocket ignition selector switch; an altimeter; a

compass and deviation card; an air-speed indicator which goes up to 600 knots; a

turn and bank indicator; an inclinometer; card holder and circuit test switch.

The pilot has a small portable oxygen bottle which will last him about half an

hour at 20,000 feet. Baka can be mothered by Betty, Liz, Peggy, Helen,

Frances or Sally [17].

Baka bomb warhead weighs 2,645 lb., including

1,135

lb. of trinitroanisol, explosive charge.

Unused baka was captured intact on Okinawa just

after invasion. Here it is examined by Marine officials.

Three exhaust nozzles located beneath tail

of bomb

discharge gas from rocket motors.

The Japanese have used suicide planes for air collisions. As early as

February 1944, anticipating B-29 raids four months before they took place, they

said, "We are now in a situation where we can demand nothing better than crash

tactics, which insure the destruction of an enemy plane at one fell swoop, thus

striking terror into his heart and rendering his powerfully armed and

well-equipped airplanes valueless, by the sacrifice of one of our fighters."

Cases of successful ramming have, however, been extremely rare. Probably the

most spectacular was on Aug. 20, 1944 when, during a B-29 raid on Yawata, a Jap

banked his plane so that it sliced off a Superfort's wing midway between the No.

1 engine and the tip. The explosion shattered both planes and flying debris

brought down a second B-29. On May 26 the Japanese began using baka

against the B-29s [18]. On night raids the mother plane turned a searchlight on a

target plane and then released baka. One B-29 shot down both a Betty and

her baka.

These and other types of suicidal defense can be expected to continue. A few

days ago a voice on Tokyo Radio exhorted the entire Japanese empire of

100,000,000 men, women and children to "rise as one Special Attack Force to

defend our own soil from enemy invasion." All of Japan has been ordered to

become a great suicide unit. The whole Japanese nation has been asked to tear

its own guts out in the very moment of trying to prevent an inevitable invader

from doing just that. Premier Kantaro Suzuki promised his nation victory "even

if, when it is won, no Japanese still is alive to enjoy it."

This is a crazy paradox and it is made even more bizarre by the fact that

many Japanese are capable of carrying out the order. Japan has been conditioned

for this irony by her history, which is not blotched with a single great defeat,

by the alarming turn this war has taken and by a queer, myth-ridden, inflated

mentality which actually might burst out of the narrow confines of the human

skull into some such madness as a national suicide pact. A Japanese

correspondent recently said over Tokyo Radio, "I even hope for an early landing

of enemy forces on our mainland, just to sense the thrill when we strike a

deadly blow to the enemy, and in expectation of worldwide amazement when our

special attack weapons display full activity."

Suicide as a military device in times of desperation is nothing new. The

British have often been able to ride handsomely to certain death; Tennyson

praised this ability after the Light Brigade made its hopeless charge. Many

awards of our own Congressional Medal of Honor celebrate moments of suicidal

glory. But there is a difference. Most military suicides have been isolated acts

of mad courage. The Japanese have done something no other nation in the world

would be capable of doing. They have systematized suicide; they have

nationalized a morbid, sickly act.

Notes

1. Shibusawa 2006, 134.

2. On May 11, 1945, the aircraft carrier Bunker

Hill (CV-17), Admiral Mitscher's flagship, was hit by two kamikaze aircraft.

Three days later, the carrier Enterprise (CV-6), Mitscher's new flagship,

was hit by a kamikaze plane.

3. The word "considerately" is a typo in

the original article that should

read "considerably."

4. The Japanese Army's Special Attack Forces

usually had special names for their units or squadrons in the same way as the

Navy's Kamikaze (meaning "divine wind"). Most Army special attack squadrons

that

made attacks during the Battle of Okinawa had the name of Shinbu (meaning

"military might").

5. The correct spelling in Roman letters of

Arima's given name is Masafumi, not Masabumi.

6. Vice Admiral Masafumi Arima did not train first kamikaze force.

The Kamikaze Special Attack Corps was not formed until October 19, 1944, four

days after Arima's death. Arima used his unit's crewmen with no special training

for a suicide attack.

7. No photographs or stories exist of a kamikaze

pilot dressed in "white funeral robes." Many photographs exist of kamikaze

pilots who dressed in typical flight suits and caps.

8. There is no mention in Japanese sources that

the ōka (baka) weapons were used in attacks against B-29 bombers. For example,

Bungeishunjū (2005) and Kato (2009), two Japanese complete histories of ōka

attacks, have no reference to the use of ōka weapons against B-29s.

9. Pilots who had been assigned to special attack

squadrons were respected by pilots and other personnel at the base, but it is

inaccurate to say that they were "worshiped."

10. Japanese sources do not mention any example

where a kamikaze pilot gave away all of his clothes so that he had nothing but a breech

clout to wear on a mission.

11. No photographs or stories exist to show that

any kamikaze pilot dressed in a white silk ceremonial robe when flying on a

final mission. Many photographs exist of kamikaze pilots who dressed in normal

flight suits and caps just before taking off on a mission.

12. The plane's guns generally remained on an

Army plane when used in a suicide attack. There are numerous photographs that

show the Army plane's guns on the plane just prior to a suicide mission (e.g.,

Osuo 1995, 53, 54, 58, 88, 91, 121, 127; Osuo 2005b, 76, 110, 123, 149, 168).

13. There were many cases when a multiple-seat

plane like the Val (Navy Type 99 Carrier Bomber) took off with the rear seat

empty, but this happened much less than half the time. For Vals that took off

from Kokubu's two airfields from April 6 to June 3, 1945, 60 kamikaze aircraft

went with a full crew of two men, and 37 planes flew with only a pilot (Osuo

2005a, 215-26). For Kates (Navy Type 97 Carrier Attack Bombers) that took off

from Kushira Air Base from April 6 to May 12, 1945, 64 kamikaze aircraft flew

with a full crew of three men, and only three planes went with only two crewmen

(Osuo 2005a, 213-24).

14. This photograph shows the Zero fighter that

crashed into the battleship Missouri (BB-63) on April 11, 1945. Admiral William

"Bull" Halsey was not aboard at the time, and the Okinawa campaign in April and

most of May was being led Admiral Raymond Spruance. USS Missouri did

become Halsey's flagship for a short time when Japanese representatives signed

the surrender documents aboard the battleship in Tokyo Bay.

15. In contrast to the author's implication,

kamikaze pilots who got captured were not necessarily malingerers and

malcontents. There are examples where kamikaze pilots were shot down by gunfire

or went down due to engine problems, and then they were captured (e.g., Kaoru

Hasegawa: see his story My Personal

History: Two Lives).

16. The weapon designated as "baka" by the

Americans was named "ōka" (meaning "cherry blossom") by the Japanese Navy.

17. The baka (ōka) weapon was carried into

battle by Betty bombers, although the Japanese Navy had studied using other

planes to carry the weapon.

18. Refer to comment in Note 8 above.

Sources Cited

Bungeishunjū, ed. 2005. Ningen bakudan to yobarete: Shōgen

- ōka tokkō (They were called human bombs: Testimony - ōka special attacks). Tōkyō: Bungeishunjū.

Katō, Hiroshi. 2009. Jinrai butai shimatsu ki: Ningen

bakudan "ōka" tokkō zen kiroku (Thunder gods unit record of events:

Complete history of "ōka" human bomb special attacks). Tōkyō: Gakken

Publishing.

Osuo, Kazuhiko. 1995. Rikugun tokubetsu kōgeki tai

(Army special attack corps). Illustrated by Shigeru Nohara. November special

edition No. 458 of Moderu Āto (Model Art). Tōkyō: Model Art Co.

________. 2005a. Tokubetsu kōgekitai no kiroku (kaigun

hen) (Record of special attack corps (Navy)). Tōkyō: Kōjinsha.

________. 2005b. Tokubetsu kōgekitai no kiroku (rikugun hen)

(Record of special attack corps (Army)). Tōkyō: Kōjinsha.

Shibusawa, Naoko. 2006. America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining

the Japanese Enemy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

|