|

|

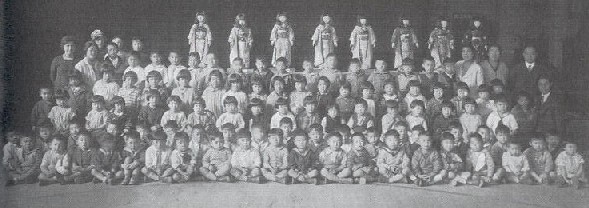

Miss Kagoshima

Japanese Friendship Doll

sent to U.S. in 1927

|

|

|

|

American museums also supplied valuable resources for the

two web sites. Several curators at museums with Japanese Friendship Dolls

supplied me with photos, articles, and other information. A visit to the 2002

exhibit of 12 original Japanese and American Friendship Dolls at the Japanese

American National Museum in Los Angeles gave me the opportunity to meet several

experts on the subject. As part of the

research for this project on Kamikaze Images, I first stepped on board an aircraft carrier when I

visited the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City. This ship's immense size and sturdy construction let

me understand firsthand how the Intrepid survived five hits by kamikaze

planes.

Many people in Japan, including journalists, museum

workers, veterans, and authors, have given me a remarkable amount of resource

material on the topics of Kamikaze Images and Friendship Dolls. With the valuable materials provided to me from Japan, I

still have numerous ideas and resources for new web pages to be added to each

site. My

research also involved searching the Internet and establishing contacts with creators

of Japanese sites and web pages on the two subjects. This collaboration with

Japanese authorities on kamikaze and Friendship Dolls has provided me many

insights that could not be obtained just by reading.

I have a special interest in how Japanese teachers present

the topic of war and peace to schoolchildren. Many elementary schools use the

story of the destruction and burning of the Friendship Dolls during World War II

to illustrate the bravery of the few teachers who managed to save them. Teachers

in today's schools also emphasize the goals of the original doll exchange: peace, friendship, and

international understanding. Starting in the 1990s, a growing number of Japanese

schools have lessons about kamikaze pilots for students as young as children in upper-elementary grades. This web site has a section that discusses these lessons

and also reviews children's books related to kamikaze pilots.

Translation - Both web sites rely heavily on

information published in Japanese, including books and web pages. Although very

difficult to quantify, I estimate there exists about 20 to 50 times more

information in Japanese than in English related to both special attack corps and

Friendship Dolls.

Although several books have been published in English on

kamikaze and other special attack corps, many stories and details on this

subject remain unavailable to English readers. In addition to this web site's

main objective to explore Japanese and American perceptions of kamikaze, I have

also tried to present different types of stories and information not published

previously in English.

In comparison to special attack forces, the topic of

Japanese-American Friendship Dolls has much less material published in English,

especially on the Internet. Therefore, many opportunities exist to translate

Japanese articles and web pages that contain new information for English

readers.

Several large Japanese web sites cover the topics of

Friendship Dolls and special attack corps. In contrast, although

English-language web pages cover these two subjects, there is no other

comprehensive English web site prepared by an American on either of these two

areas. However, two Japanese sites, one on kamikaze and another on kaiten

(manned torpedo used in suicide attacks), have many translated pages in an

attempt to provide information on special attack forces through the Internet.

Angles and Links - The topics of Kamikaze Images and

Friendship Dolls both have countless angles that can be turned into articles or

web pages. Each doll has a distinct history, and many people have their own

individual stories about a specific doll. In much the same way, each kamikaze

pilot has his own history, and bereaved family members and other people who knew

the pilot also may have their own stories. Moreover, many kamikaze pilots and

other special attack corps members were waiting for attack orders or were in

training when the war ended, and these people also have individual accounts about

their experiences.

Local newspaper articles provide a valuable source of

information for both the special attack corps and Friendship Dolls. Journalists

often try to link local residents to historical events, and both topics provide

many opportunities for this. On August 15, the anniversary of the end of World War II,

many Japanese local newspapers publish articles on residents' wartime

experiences, including those of former kamikaze pilots or those of bereaved

family members or war comrades of pilots who died. As another example, Japanese

elementary schools and kindergartens often call local newspaper and television

reporters when they hold events related to their Friendship Dolls.

Many relationships exist between various pieces of

information about Kamikaze Images and Friendship Dolls. Therefore, the

ability to link to other web pages on the same site or to pages on external web

sites allows readers to better understand these connections. If other web pages

cover a specific area related to my two sites, I have tried to link to these

pages rather than duplicating the information.

Since so many different potential stories and topics exist

for individual web pages, I have tried to develop a flexible structure for both

web sites to allow pages to be added indefinitely.

Intersections - During my 2004 trip

to Japan, a former kamikaze pilot who lives in Kagoshima City accompanied me

when I gave a talk to children at a juvenile protective care facility with a new

Friendship Doll from America. As I did the research for this web site on

Kamikaze Images, I found a few points where the

stories of kamikaze pilots and Friendship Dolls intersect.

In one example, Shigeo Imamura, the son of Japanese

immigrants, grew

up in California until 1932 when at the age of ten he moved with his parents to

Japan. He later became commander of a kamikaze squadron in the Japanese Navy.

Imamura (2001, 6-7) saw the Japanese Friendship Dolls in San

Francisco when eight of them visited Kinmon Gakuen (Golden Gate School) in 1927.

When he moved to Japan in 1932, he become good friends with one of the grandsons

of Sidney Gulick, who organized the Friendship Doll Project in 1926 and 1927

(Imamura 2001, 23-5).

Japanese Friendship Dolls with kindergarten children in auditorium

of Kinmon Gakuen (Golden Gate School) in San Francisco (1927)

The 1993 documentary novel Gekkō no Natsu (Summer

of the Moonlight Sonata) tells the story of two kamikaze pilots who visited an

elementary school near their Army air base in 1945. One pilot who had studied

piano played Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata on the grand piano at the school, and

the students warmly said goodbye to the two young men as they departed. The teacher who

had heard the kamikaze pilot play Moonlight Sonata found out in 1989 that

the school wanted to get rid of the old grand piano. She told a school assembly

of her great love for the piano and of its historical significance, so the

school decided to have the piano restored to its original condition.

The novel Gekkō no Natsu (Mōri 1995, 141-5) also

relates the story of this same teacher's great sorrow during the war when the vice-principal

burned her school's Friendship Doll from America. This teacher had seen the

blond-haired American doll in a dress with white lace frills stored in a wooden

box in the principal's office with the words "Mary, Massachusetts"

written on the outside. Many of the American dolls cried out "mama" when moved,

which the doll did as the vice-principal burned it for being a spy from

the enemy. Sometimes when the teacher's two daughters said "mama," she

remembered Mary's fate with sadness. After she heard that the school where she

had taught also planned in 1989 to get rid of the grand piano on which the kamikaze

pilot had played the Moonlight Sonata, she sadly remembered back to the war years when

she could not stop the school's Friendship Doll from being destroyed.

Sources Cited

Imamura, Shigeo. 2001. Shig:

The True Story of an American Kamikaze. Baltimore: American Literary

Press.

Mōri, Tsuneyuki. 1995. Gekkō no natsu (Summer of the

Moonlight Sonata). Originally published in 1993 by Chōbunsha. Tōkyō: Kōdansha.

Shirai, Atsushi. 2002. Tokkōtai to wa nan datta no ka (What

were the special attack forces?). In Ima tokkōtai no shi o kangaeru

(Thinking now about death of special attack force members), Iwanami Booklet No.

572, edited by Atsushi Shirai. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten.

|